What have we here?

What Have We Here? Co-curator Hew Locke

Review of exhibition and catalogue by Brian Durrans

Widely respected, much visited and often criticised as a treasury of imperial loot, the British Museum recently organised an exhibition called What Have We Here? (1) Co-curated by British Guyanese artist Hew Locke and curator Indra Khanna in collaboration with British Museum curators, it conveyed something of the scale and brutality of Britain’s colonial empire using selected objects, artworks, documents and images, mainly from the British Museum’s but some from other UK collections.

What Have We Here? had much to say about both the history of the around 200 objects it featured and how they came to the Museum. The catalogue suggests possible reasons why the British Museum organised the exhibition at this time, but that subject deserves more space than can be spared here. This review therefore simply sketches the exhibition’s coverage and discusses a few highlights and how it tackled its theme.

EXHIBITING COLONIALISM

The exhibition showed how colonial power has been asserted through symbols like portraits, crowns, thrones, or coats of arms, which sometimes appropriate objects or images of the colonised themselves; the relationship between trade, armed conquest and various forms of subjugation; and the colonial conversion of objects of veneration or symbolic or simply utilitarian purpose into trophies, treasure, art or trash.

The show was organised around specific examples of colonisation mainly in Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia), Asia (India, China) and the Americas (Caribbean and the Atlantic seaboard of north America). The Atlantic slave trade was, understandably, a major theme. Attention was also given to pre-colonial trade and varied forms and fortunes of anti-colonial resistance. There was more information about them in the exhibition itself and even more in its still-available catalogue, but three items, selected here more or less at random – a mask, a gun and a print – give a sense of different aspects of colonial power conveyed in the exhibition.

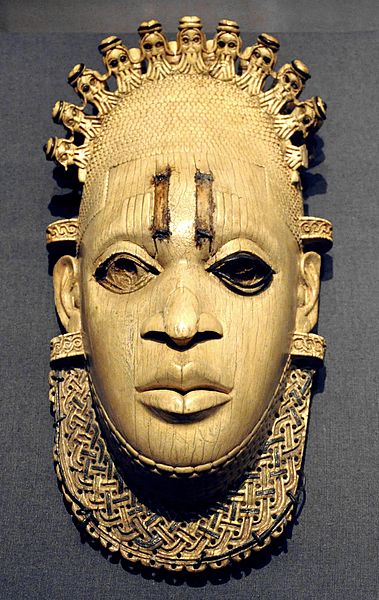

MASK (from Nigeria yet in one sense via London to the world)

In 1897, from the Oba’s (King’s) bedroom in his palace in Benin City, soldiers of the British ‘Punitive’ Expedition stole what would become an epitome of sub-Saharan creative genius: the 16th century pendant ivory mask commemorating Queen Mother Idia of the Edo people in Nigeria. The mask’s dignified face looks more serious than the Mona Lisa’s but is similarly inscrutable. Ten Portuguese figures, inlaid with copper, form an openwork arc from ear to ear, over the top of the head. Since the late 15th century, Portuguese engaged with Benin in the ivory trade and as mercenaries against its rivals. The mask was one of five made or commissioned by Idia’s son in the first half of the sixteenth century to be worn by successive Obas on ceremonial occasions.

Stealing the mask undermined the exiled Oba’s authority but after the British Museum bought it in 1910, it was seen by thousands of museum visitors and by many more via photographs, drawings and copies. It then became widely known and admired but mostly understood as a stand-alone art object rather than part of Edo royal regalia. Despite repeated requests for its return to Nigeria along with the Benin ‘Bronzes’, it remains in the Museum.

The mask was never loaned but, in what was described as “a potent decolonial move” (catalogue, pp32-34; see also pp137-39), its image was adopted as the emblem for the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC), held in Lagos and Kaduna in 1977. This description captures the power of what has been done with the image, despite or even because of the “exile” of the mask itself: but the “decolonial move” might be better seen as part of an ongoing chess game at least until Nigeria on the up escalator meets Britain on the down to facilitate an equitable settling of cultural accounts.

Since colonisation entailed much more systemic injustice than just stealing cultural artefacts, and persists as neo-colonial indebtedness of the global South, (2) so decolonisation must amount to more than merely moving objects between museums. Whether such moves can play more than a symbolic role in weakening imperialism remains to be seen.

MACHINE GUN (British, used in China)

The second item in the display I’d like to focus on is a rapid-fire Maxim machine-gun of the type used by troops of the 1903-04 Younghusband Expedition to slaughter more than 700 Tibetan soldiers, armed only with swords and single-shot rifles, in what became known as the Massacre of Chumik Shenko. That day, 31 March 1904, the commander of the British detachment followed his general’s orders but later wrote “I hope I shall never again have to shoot down men walking away” (catalogue, pp29-32, 154; “walking away” would today and possibly then be a euphemism for “in the back”). During the entire Expedition, some 2-3,000 Tibetans are estimated to have been killed. It was in 1927, less than a quarter of a century later, that Mao Zedong is reported to have first used the expression “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”. Perhaps he had Chumik Shenko in mind.

Although the displayed object was not one actually used against the Tibetans, its physical presence, amplified as an image in some of Locke’s 2D prints, makes the Younghusband episode almost as unforgettable as if it had been.

Unlike in Benin only seven years before, the Younghusband expedition of 1903-1904 included two British Museum representatives who were instructed to collect books and manuscripts for their employer. They did as they were told. It took 400 mules to extract the spoils of armed aggression from the country. In 1905 the Museum bought an amulet, lama figure, chalice and wicker shield from the expedition’s Chief of Staff. Other items derived from this imperial looting and killing spree still occasionally come up for sale, its notoriety only making them more collectable (catalogue, p154).

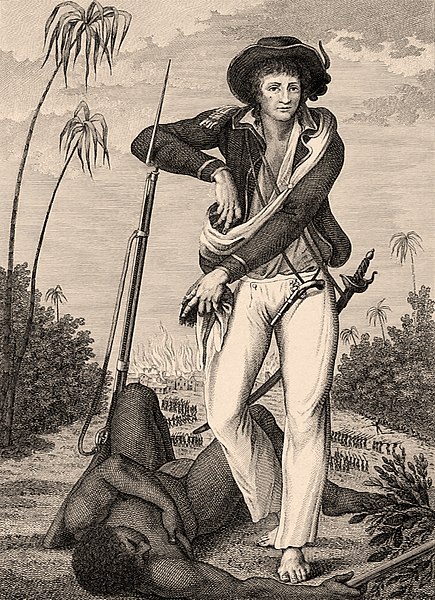

PRINT (British but featuring Suriname)

The last of my three chosen expressions of colonial power would have been easy to overlook but speaks volumes and especially to the imperialist present. Throughout the exhibition, Locke cites evidence that colonialism was not just brutal but resisted by the colonised themselves. A book by Dutch Scottish soldier John Gabriel Stedman, published in 1796, describes his personal experience of the suppression of a slaves’ rebellion in Suriname (then Dutch Guiana), illustrated in sometimes horrific detail by William Blake.

Locke, however, drew attention to the book’s frontispiece, from an etching by another artist, showing a dead or dying slave on the ground, above whom stands his nemesis, a white European soldier armed with sword and pistol, his right arm resting on a rifle as tall as himself and his left hand indicating his victim. The soldier is author Stedman himself and the couplet quatrain below the frame of the image is his repellent excuse for both the scene depicted and the other examples of inhumanity which the book is about to reveal to the reader, even though much of its content was about the author’s love life and the colony’s natural history:

“From different Parents, different Climes we came,

At different Periods;” Fate still rules the same.

Unhappy Youth, while bleeding on the ground;

‘Twas Yours to fall _ but Mine to feel the wound. (3)

The book went on to fuel the abolitionist cause, but Stedman’s grotesque stanza is a monument to the moral bankruptcy of imperialism as a whole. Whilst the death of those subjugated by colonial rule or challenging it was condoned by fate or God, we are meant to believe that so was the conscience that paid at least as high a price for it.

The poem echoes the “manifest destiny” of US settler colonialism fifty years earlier in its genocide of indigenous north Americans; and it anticipates, a century later, Kipling’s poem The White Man’s Burden (1899, urging US colonisation of the Philippines). In the next century, Bob Dylan nailed such hubris in With God on Our Side and, in The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll (both songs 1964), charging high-minded apologists for racist murder as “you who philosophize disgrace”. Yet imperialism’s more recent deceptions, such as “humanitarian intervention” or “right to protect”, still garnish their vastly deadlier firepower with the same old brand of conspicuous remorse. Stedman would have a column in The Guardian.

THE WATCHERS

The most enigmatic of Locke’s own artworks in What Have We Here? deserve a brief comment. The Watchers were semi-abstract, flamboyantly-dressed, carnivalesque figures, roughly three-quarter life size, stationed above the display cabinets to “look” at visitors looking at the exhibits. Except that they were silent, Locke suggests they worked like a Greek Chorus to comment on the action. The ancestors or descendants of the makers, or gods, security guards, or even the British Museum’s own trustees? Whoever they were, they added an uncanny dimension to the visiting experience for anyone distracted from the engrossing exhibits themselves.

CAVEAT

Presented as an artist’s installation, What Have We Here? was naturally non-didactic. The exhibition’s coverage ends in the early 20th century. It showed colonialism in lockstep with capitalist greed, but colonialism’s segue into modern imperialism was nowhere in sight. By ignoring their historical relationship, the exhibition made “colonialist” and “imperialist” equivalent terms of disapproval, prudently insulating itself from the reality that British imperialism currently has 145 overseas military bases and no doubt support among the Museum’s visitors, trustees and present and potential future funders.

FACTS AND ARTEFACTS

The gallery hosting the exhibition was created as part of the British Museum’s Great Court project for the new millennium with the original 1857 round reading room at the core. What Have We Here? was therefore only a few metres from where Marx and Engels in the second half of the 19th century, and Lenin in the early 20th, sat working on sources in that library to track the development of capitalism and imperialism in Britain and elsewhere. Writing from exile in Geneva in the first half of 1916, Lenin drew on that work to define the special features of imperialism that were emerging almost exactly a century before the Great Court was completed. (4) Those studies embraced the rise of imperialism up to their own day, with special emphasis on its current forms emerging from colonial antecedents and described them in the standard terms of historical political economy, such as scales of investment, production, distribution, consumption, wages, profits, competition for resources, labour and markets, and the drive to war.

Although What Have We Here? paid special attention to money and share certificates, and the rise of commodities, its main interest was in the colonial conversion of objects’ indigenous use and exchange values into those required for colonial trade and for buttressing the authority on which it depended.

It turns out that the political economists and curators were exposing the power of capital by complementary means.

The reviewer is a long-retired British Museum curator with a critical interest in cultural politics.

(1) British Museum paying exhibition (£16 / concessions, free Fridays), 17 October 2024 – 9 February 2025; catalogue, 2024, £25).

(2) E.g., Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London, 2018 [1972])

(3) Emphases in the original. The poem is irredeemable. In Scots the words “ground” and “wound” can rhyme.

(4) V.I. Lenin, Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism (Petrograd, 1917)

Commemorative mask of Queen Mother Idia, permanent collection of the British Museum. Photo by Andreas Praefcke

Frontispiece of book by John Gabriel Stedman