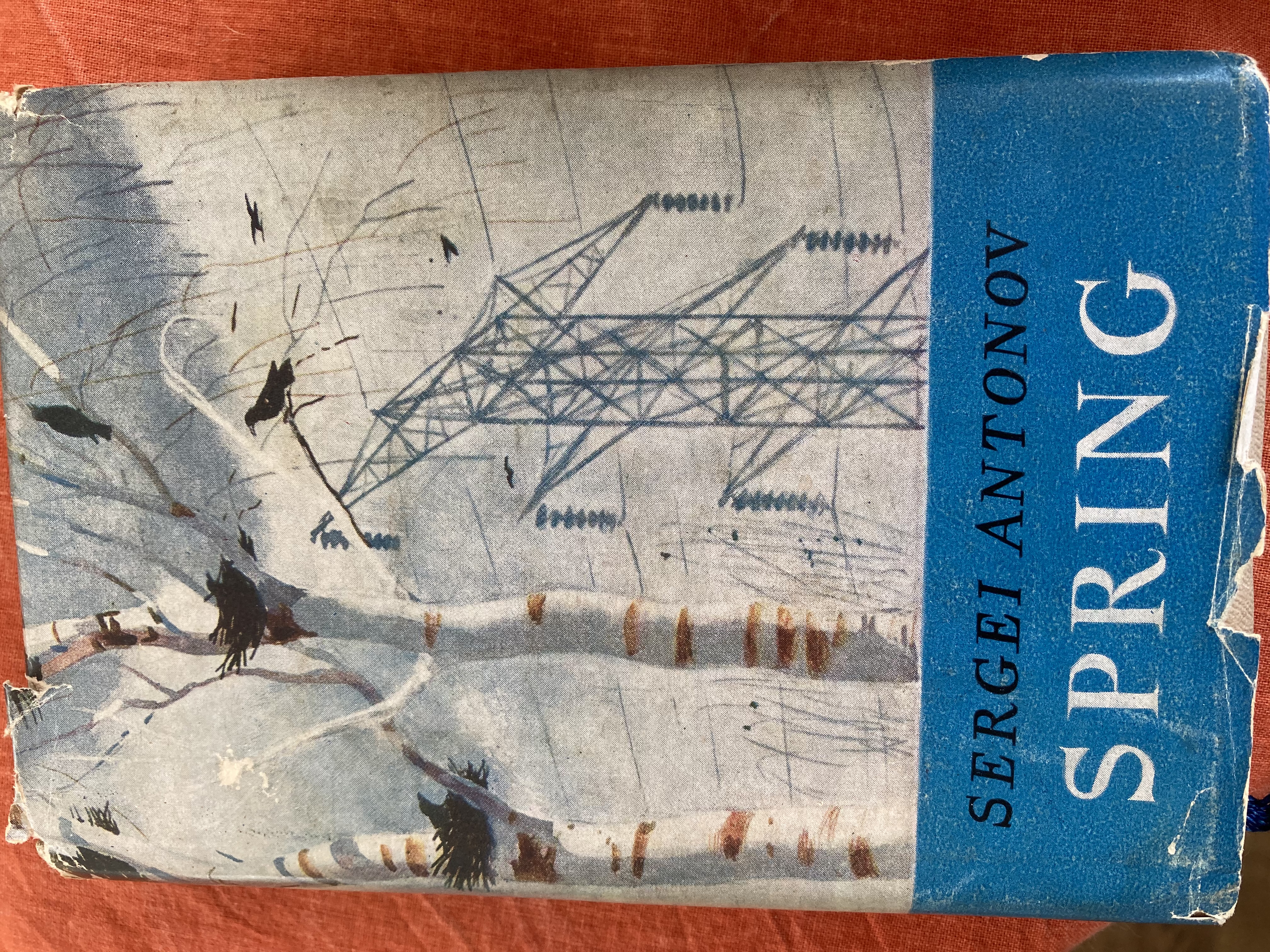

Spring by Sergei Antonov

Reviewed by Marianne Hitchen

It is often worth remembering how the first socialist country, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was built despite great hardship and two world wars. How was it possible for this poor, underdeveloped country to transform itself into a major power, and its people to win themselves material security and freedom from serfdom, inequality and ignorance?

In Sergei Antonov’s collection of stories called Spring, you begin to discern the answer: monumental collective effort, participation in organising and decision making, enthusiasm, pride, determination, excitement, belief in what they were doing and why they were doing it, and very, very hard work. Written between 1947 and 1952, Antonov brings these years to enthralling and immediate life, through five tales of people responding and adapting themselves to their conditions, while describing their particular efforts to rebuild a country devastated by war.

It isn’t easy finding out about Sergei Antonov these days, partly because his name is the Russian equivalent of John Smith (and the internet is full of cellists and Yale professors of the same name), but also because the period in which he lived and wrote about is being falsified and quietly written out of history. In the furthest pages of Google you eventually find brief biographies on the Good Reads website, and in the Free Dictionary, which cites The Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, 3rd edition (1970-1979).

Born in 1915 in Petrograd into the family of a railway engineer, Sergei Antonov travelled widely in southern Russia, the Urals, the Volga region and Central Asia as a child. After school he worked as a handyman on construction sites, and on graduating from the Leningrad Highway Institute in 1938, became a civil engineer then a teacher in a technical school. He fought on the Soviet-Finnish and Russian fronts of the Second World War (the Great Patriotic War as it was known in the USSR), where he commanded engineering and sapper units. After initially publishing poetry in 1943-1946, his first story Spring appeared in 1947. Novellas and film scripts followed, for which he received the State Prize of the USSR, the Order of the Red Banner and the Stalin Prize (1951).

Antonov’s stories focus on individuals and the part each of them plays in building a new society, and are characterised by beautiful descriptions of nature:

“It was almost five o’clock in the morning. Dawn was breaking; the sky over the birch grove was delicately flushed, but the sun had not yet come up. The birds were still asleep. Someone was lighting a fire in the last house of the village which straggled along the edge of the ravine, and thin fibres of smoke rose placidly into the sky.” (Morning 1949)

His stories centre around people of all walks of life and personalities, who are always thinking, working (often through the night), learning, dealing with difficulty, getting on each other’s nerves, and making discoveries about themselves and other people. In this excerpt from Rain (1951), a dissatisfied office manager struggles to adapt to the new world:

“The train was moving before she knew it. And although it was she who was leaving and Nepavoda who was staying, it seemed to her that she was standing still and Nepavoda and the little station and the highway along which she had come into town and the glistening trees and the fragrant rain-drenched earth and the soft low sky - that all these things had begun to move and were slowly wheeling away from her. Suddenly she remembered Pasha, and clever ungainly Timofeyev, and the inquisitive brigade-leader Olga, and the bearded man wearing the discarded army coat, and Engineer Gnatov, and the disapproving driver; and she was bitterly sorry that all these people, who had just begun to respect her, were receding faster and faster into the distance, and perhaps she would never see a single one of them again”

This description of wheat could only have been written by someone who helped to grow it, and understood its value:

“On every hand, stretching away to the very edge of the forest, was the ripe wheat, stirring faintly. The heavy ears waved in the breeze, sending a soft rustle, a thin ring, a faint whistle over the plain. A silvery path of moonlight shimmered on the stalks, and suddenly I felt calm and happy”. (Spring 1947)

After reading this book, it is impossible not to grieve and wonder at how this passion and commitment came to be squandered. These stories are a vivid reminder of what is lost.