Quantitative easing, post-lockdown crisis and the super-rich

November 2021

By Noah Tucker

Well into our second year since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus pandemic, the world capitalist economy is now also suffering from a new malaise, a global economic pandemic involving some symptoms which seem entirely new and others which have not been seen for many years. But, however unfamiliar they appear, these symptoms can only be understood in terms of capitalism, and of the actions taken by the capitalist states and central banks to shore the system up. As a consequence of Covid, this is both a crisis of the pandemic and the panacea. It involves price inflation. This is not caused by workers demanding higher pay, but by the use of monetary policy to protect big business and the ultra-rich. Yet Labour right wingers, such as Wes Streeting, speak as if higher wages would lead to an inflationary spiral. (1)

SUPPLY, DEMAND AND WAGES

In Britain, we hear the parochial claims that our ‘empty shelves’ in shops are mainly caused by Brexit, and accusations that, for instance, the rocketing prices for gas and electricity are all the fault of Vladimir Putin. So it is worth hearing an American account of this malaise. As Derek Thompson wrote in The Atlantic:

“The U.S. economy isn’t yet experiencing a downturn akin to the 1970s period of stagflation. This is something different, and quite strange. Americans are settling into a new phase of the pandemic economy, in which GDP is growing but we’re also suffering from a dearth of a shocking array of things—test kits, car parts, semiconductors, ships, shipping containers, workers. This is the Everything Shortage.

The Everything Shortage is not the result of one big bottleneck in, say, Vietnamese factories or the American trucking industry. We are running low on supplies of all kinds due to a veritable hydra of bottlenecks…

The most dramatic expression of this snarl is the purgatory of loaded cargo containers stacked on ships bobbing off the coast of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Just as a normal traffic jam consists of too many drivers trying to use too few lanes, the traffic jam at California ports has been exacerbated by extravagant consumer demand slamming into a shortage of trucks, truckers, and port workers. Because ships can’t be unloaded, not enough empty containers are in transit to carry all of the stuff that consumers are trying to buy. So the world is getting a lesson in Econ 101: High demand plus limited supply equals prices spiraling to the moon. Before the pandemic, reserving a container that holds roughly 35,000 books cost $2,500. Now it costs $25,000.” (2)

Indeed, these are all manifestations of insufficient or reduced supply in a global market economy, unable to meet high or even merely maintained demand, resulting in shortages and rising inflation. But this appears to be the opposite of the kind of economic crisis which capitalism usually generates due to the internal processes of the capitalist market.

Thus for example, in 1921 to ’22, then in the depression following the 1929 crash, and more recently in the crisis of 2008 and onwards, the underlying problem was more and more goods and services being produced (with the expectation of profits) than people could afford to buy, because, in the interests of profits, their wages being kept too low to purchase all those goods and services. The result during those classical capitalist crises was not shortages and higher inflation, but unsold products, high unemployment and a risk of deflation. Deflation is a special worry for economists because it can lead to a spiraling vortex of falling prices and plunging profits, as occurred in the 1930s - hence central banks being given inflation targets, to ensure average prices keep rising at least one or two annual percentage points above zero.

Before going further, an upside to the present debacle must be acknowledged. The perennial economic struggle between workers and employers, i.e. between labour and capital, is one in which, paradoxically, the fewer there are who are willing and able to supply their labour (or to be more exact, who are willing and able to provide that labour at a particular price) the stronger becomes the side of the workers and the weaker the position of the employers. Our current situation follows decades of wages stagnating, and even falling in many instances. The impact of this in Britain was masked in recent years by the employment of workers from eastern European countries where average pay rates are even lower. Although far from being the main cause, Brexit has made a contribution to the changed situation in Britain. Now, with a workforce whose availability has been reduced mainly due to Covid, workers are sensing the improvement in their relative power and are pushing for better pay. In the USA, the 10th month of 2021 was dubbed ‘Striketober’ because of the surge in industrial disputes. Britain is also seeing a wave of action and pay demands by workers, with successes recorded from the binmen’s strike in Brighton to, Liverpool lorry drivers who have won a 17% pay rise.

Alongside the ramifications of coronavirus, there are other factors impacting the supply side of the economy. Among them, there is the age profile in some industries, with big proportions of workers approaching retirement (this itself having resulted in large part from low pay and harsh conditions which young people are reluctant to sign up for); last year’s cold winter in Asia, resulting in the depletion of gas stocks; and the fragility of the global supply chain, with reserves cut to the bone to reduce costs and boost profits. But the trigger and the common element to the ‘hydra’ of restrictions on supply is the impact of Covid and the lockdown measures. And it is the monetary response of governments and central banks, acting to protect the big corporations and the wealthy in these conditions, which has unbalanced the other side of the equation - demand.

MIDDLE AGES CRISIS

Two historical examples of epidemics followed by economic and social disruption have been widely studied: the Black Death, which peaked in Europe between 1347 and 1351, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 to 1920. Although nearer in time, the lessons of the 1918-20 pandemic are somewhat less clear because the lockdown period was relatively brief and its immediate economic impact in most advanced capitalist countries was relatively low in comparison to Covid-19, and its wider effects merge with those of the end of World War 1, demobilisation and the return to a peacetime economy.

The Black Death, on the other hand, was an enormous event with utterly devastating human cost. Estimates of the proportion of the European population who died vary from 30% to 60%. This tragedy, however, led to an improved bargaining position for the surviving peasantry and rural and urban workers. In England, the ruling classes of the time were so alarmed by this that they enacted two pieces of legislation, the Ordinance of Labourers (1349) and the Statute of Labourers (1351). The preamble of the latter complained that:

“Whereas lately it was ordained by our lord King and by the assent of the prelates, earls, barons and others of his council, against the malice of servants who were idle and not willing to serve after the pestilence without excessive wages, that such manner of servants, men as well as women, should be bound to serve, receiving the customary salary and wages… it is given to the King to understand in the present parliament by the petition of the commons that the servants having no regard to the ordinance but to their ease and singular covetousness, do withdraw themselves from serving great men and others, unless they have livery and wages double or treble of what they were wont to take in the twentieth year and earlier, to the great damage of the great men and impoverishment of all the commonality…” (3)

The act commanded all able-bodied persons under the age of 60, with no other means of support, to work for any employer that required them, and it set maximum wage rates based on the pre-plague pay levels prevalent in 1346, with terms of imprisonment of forty days for a first offence, followed by a quarter of a year for subsequent offences. This legislation did somewhat restrain the pressure for better pay, but the main factor which defeated the aspirations of the ‘malicious servants’ for a higher standard of living was a change in the money supply. As Professor David Routt of the University of Richmond, Virginia notes:

“In some instances, the initial hikes in nominal or cash wages subsided in the years further out from the plague and any benefit they conferred on the wage laborer was for a time undercut by another economic change fostered by the plague. Grave mortality ensured that the European supply of currency in gold and silver increased on a per-capita basis, which in turned unleashed substantial inflation in prices that did not subside in England until the mid-1370s and even later in many places on the continent. The inflation reduced the purchasing power (real wage) of the wage laborer so significantly that, even with higher cash wages, his earnings either bought him no more or often substantially less than before the magna pestilencia. (4)

To be clear, what caused the post-plague inflation, which devalued the workers’ gains in money wages, was not cost pressure from the wage rises themselves, but the fact that the Black Death had killed off people, while the same amount of gold, silver and coins remained as before- therefore the supply of money per person rose rapidly. This was accompanied in 1351 by an official reduction in the weight (per coin) of English silver coinage, creating additional funds for the King without having to impose taxes on the barons, earls and prelates, while further devaluing the value of the currency. With production now limited by the smaller size of the surviving labouring and peasant population, rampant inflation took hold, reducing or even wiping out the gains in real wages.

So should the workers of the mid-14th Century have therefore limited their aims, and refrained from demanding higher pay for fear of setting off a wage-price spiral? Definitely not. Had they not achieved higher money wages, the value of their pay would have slid even further behind prices, as the inflation which occurred was due to increased monetary demand resulting from a completely different and independent cause. That was the huge per-person increase in the amount of money, the bulk of which, of course, was in the coffers of the ‘prelates, earls, barons and others’ of the ruling class, rather than in the pockets of labourers and peasants.

The parallels between 1351 and 2021 are for sure inexact. One of the main differences is that the recent vast increase in the money supply via ‘quantitative easing’ is entirely deliberate.

QE A FREE LUNCH FOR THE ULTRA-RICH

Deployed by the central banks and governments of all the major advanced countries which have their own currencies, and by the authorities of the EU’s Eurozone, quantitative easing has become the all-purpose method of choice for ensuring that those who benefit most from capitalism continue to prosper irrespective of systemic economic challenges, and that cuts in public services and incomes for the masses can be implemented without destabilising effects on the overall economy.

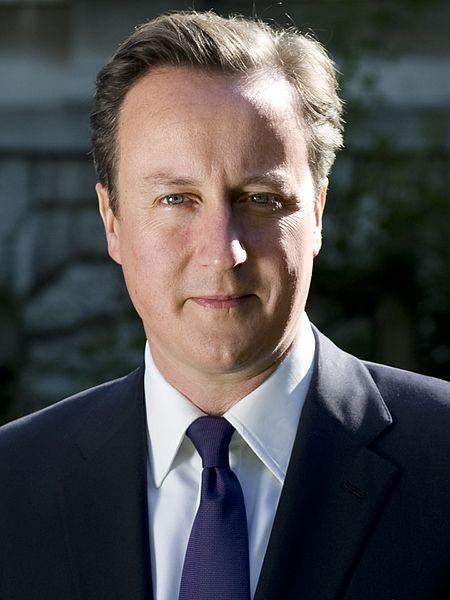

There are innocent claims, cloaked in abstruse jargon, that the purpose of QE is merely to expand the volume of money so as to prevent the inflation rate from falling too low, thus fending off the danger of deflation. In fact QE is the electronic printing of many hundreds of billions (of pounds, dollars, yen etc) which are provided by the central bank, via purchases of government bonds, to the central government. Since the crisis of 2008, QE has become a major source of state revenue for the advanced capitalist powers. Due to the prominence of the City of London in global finance, Britain was uniquely (for a major advanced country) exposed to the impact of the 2008 crash. For the Conservative leadership under David Cameron, the depth of the crisis, which was still unresolved in 2010, provided both the need for a radical way out, and an opportunity. The chosen way forward avoided the need for any increased taxes on the rich, or any increased control by the state in the productive economy. This way forward, which became known as ‘austerity’, was made possible by quantitative easing.

QE played a hugely important and almost entirely unacknowledged role in facilitating the deep austerity cuts under the Tory/Lib Dem coalition government of Cameron, Osborne and Clegg from 2010 to 2015. These were, effectively, big transfers of resources from the poor and the general population to the very rich. The huge scale of the cuts in the public sector, combined with the reductions in the purchasing power of the population due to cuts in wages, would have sent the economy, and with it the public finances, go into a steep nosedive if the government had had to rely only on revenue from taxation on the mass of the population and borrowing from the private markets. (This was indeed predicted by former Monetary Policy Committee member Danny Blanchflower.) But a third major source of revenue had been discovered – the provision of newly minted electronic cash, supplied almost directly by the Bank of England.

Given the ongoing deflationary ramifications of the 2008 crash, combined with the effects of austerity, the British state was able to create and spend £435 billion of its own money from QE, without causing any rampant inflationary effects except for the big rise in asset values. That, of course, was a very welcome side effect from the viewpoint of the ultra-rich, who have accrued large increases in wealth as a result. But the real value of QE is more than just a side effect. The value is that governments have, so far, been able to meet major economic challenges to the system that benefits the very rich, and even to make changes that skew the system further in their favour, without facing economic meltdown and without having to draw on the wealth of the very rich via taxation, or reduce their power.

Hence, in dealing with the challenges of Covid and its consequences from early 2020 onwards, the advanced capitalist states reached for QE as their monetary tool to address the challenges of the pandemic and lockdown, to avoid increasing income taxes on the top 1%, or implementing wealth taxes on them, or instead of intervening more directly in the economy. In Britain alone, an additional £450 billion has been created in QE money since March 2020, covering for the extra costs of lockdown (the furlough scheme cost a ‘mere’ £69 billion up to the end of August 2021) plus the losses to the Treasury due to reduced economic activity. (5)

One consequence has been the highly unusual phenomenon of wealth increasing during a recession. As noted in a Resolution Foundation report in August 2021, the bulk of this wealth has been accrued by the richest. The 2021 Sunday Times Rich List recorded an extremely rapid rise in the wealth of the extremely rich, with a 24% increase in the number of billionaires in Britain to 171, with a combined wealth increase of 21.7%, to a total of assets of £597.2 billion, though this is probably an underestimate. (6) As a phalanx protecting the almost unbelievable riches of these 171 individuals stands not only the British government, but also the new leadership of the Labour Party, which refuses even to contemplate requiring this tiny elite to pay a bit more in tax.

ROOSTING CHICKENS

But as the current situation shows, monetary policy does not provide an everlasting ‘free lunch’ without consequences, even for the very rich. Politically also, the processes of class society, whether purely internal or when impacted on by other phenomena, e.g. a pandemic, always favour the richest but nevertheless inevitably rebound in rebellion. The Black Death, and subsequent inflation and repression of wages, was followed by Peasants’ Revolt. World War 1, the Spanish Flu and 1921-22 crisis were followed by the 1926 General Strike. The crisis of the 1930s and World War 2 were followed by the 1945 Labour government, the nationalisation of some industries and the welfare state which lasted for a generation. The 2008 crash led to the anti-austerity movement, which for a few years made Jeremy Corbyn the leader of the British Labour Party.

So far in the lockdown and post-pandemic period of 2020 to 2022, the working class is winning some strikes. There will be more to come.

(1) https://twitter.com/Angry_Voice/status/1446064043840655360

(2) America Is Choking Under an ‘Everything Shortage’ - The Atlantic

(3) https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/citizen_subject/transcripts/stat_lab.htm

(4) https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economic-impact-of-the-black-death/

(5) https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9152/CBP-9152.pdf

Container ship in Los Angeles photo by Downtowngal

Two historical examples of epidemics followed by economic and social disruption have been widely studied: the Black Death, which peaked in Europe between 1347 and 1351, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 to 1920.

David Cameron