Policing the borders of paradise as Schengen disintegrates

by Clare Bailey

‘Europe is a garden. Most of the rest of the world is a jungle and the jungle could invade the garden.’ October 2022, Josep Borrell (head of the European External Action Service – the EU diplomatic service.

When top EU diplomat Josep Borrell described Europe as a garden and the rest of the world as an invasive jungle, he gave unusually clear expression to the racist underpinnings of EU foreign policy – a policy enacted not only in high-level diplomacy and official statements, but also more directly and lethally at the EU’s external borders by Frontex, the EU’s border agency.

FRONTEX EXPANSION

Frontex came into being under a more cumbersome name in 2004 as a small organisation with a few hundred officers. Its powers and size have grown exponentially in the last five years and there are plans to expand them much further. Standing ambiguously – and ambitiously – as something between an army, an intelligence agency and a police force, Frontex is the only EU agency with a uniform. Its annual budget has grown from €6m in 2005 to €922m in 2024, most of that growth taking place in the last 3 years.

Its headquarters are in Warsaw where its directors oversee an organisation with around 8000 officers, all potentially armed, expanding to 10,000 by 2027. Frontex has its own planes, boats and vehicles, which supply and use its border surveillance system EUROSUR. From mid-2025 Frontex will be introducing the new European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS) designed to further strengthen Europe’s internal security with pre-travel screening for all non-EU travellers. It also has powers to act independently, without the consent of Member States, in undefined “exceptional circumstances” (EU Regulation 2019/1896).

Frontex operations are not confined to EU countries with external borders; its reach is growing. As of October 2023, it had nearly 600 staff deployed across ten joint operations or ‘partnerships’ in eight non-EU countries, including Moldova, Albania, Montenegro and Serbia. As part of EU plans to externalise its borders, Frontex is attempting to set up a similar operation in Tunisia, with whom it already has a contentious agreement on migration control.

LACK OF ACCOUNTABILITY

Frontex is an opaque agency. It is officially accountable to the European Parliament but MEPs have found it almost impossible to hold it to account, and the legal teams of organisations campaigning for the rights of migrants have great difficulty in obtaining Frontex documents that should be in the public realm, as EU regulations stipulate, “The Agency… shall make public relevant information, including…comprehensive information on past and current joint operations…”. (EU Regulation 2019/1896) This would include information on all interventions, return or ‘pushback’ operations, and repatriation deals with third countries.

In April 2022, Sea-Watch, the maritime search and rescue organisation, filed a lawsuit for the release of information proving Frontex’s involvement in human rights abuses, “For two decades, the EU has been investing billions in an organization (Frontex) that operates with impunity and without transparency, like a secret service, and is particularly notable for its human rights violations.”, said Bérénice Gaudin of Sea-Watch

Frontex had previously refused all requests under the EU Freedom of Information Regulation. Despite this blatant refusal to cooperate, the General Court of the European Union in Luxembourg, in a ruling on April 24th this year, predictably failed to impose transparency and accountability on Frontex and a complaint process via the European Ombudsman, which found in favour of the complainant requesting access to documents, resulted only in Frontex agreeing to ‘consider’ releasing them. But investigation of Frontex’s activities over the past few years by determined journalists has nonetheless brought some previously hidden documents and records to light and following these investigations and some unfavourable public attention, Frontex was accused of acting outside its remit and of not being compliant with EU human rights laws. It was then subjected to greater scrutiny by the European Commission itself, since when its public documents have been careful to stress its human rights concerns.

FORTRESS EUROPE - PROTECTING SCHENGEN

Frontex’s core task is to ensure the proper functioning of Europe’s Schengen Area – the area governed by the 1985 Schengen Treaty inside which movement between countries takes place without border controls, facilitating the free movement of labour and goods within the EU. Assuming national responsibilities of the states concerned where and when necessary, and thus far by agreement, Frontex controls these external borders with a particular emphasis on the designated key ‘access routes’ into the Schengen area via the Mediterranean. These gateways into the EU are defined by Frontex as: the Eastern route via the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean; the Central Mediterranean; and the Western Mediterranean. Between them they account for most ‘illegal’ entries into the EU.

Since 1993, alongside Frontex air and sea patrols, 40,000 people have drowned attempting the crossing from the North African coast in unsafe, overcrowded boats. SOS calls go unanswered and search and rescue missions by Sea-Watch and other organisations are impeded. This is the world’s most lethal migrant route, “Instead of offering those seeking protection legal and safe routes, the borders are being turned into a human rights-free space and the Mediterranean into a mass grave,” Bérénice Gaudin

Other organisations monitoring the EU’s migration policy are of like mind. In an article published in April 2023, the European Institute for International Relations – a research centre for international law – ascribes Frontex aggression in the Mediterranean to the EU’s treatment of migration as a security problem. Referencing the International Organisation for Migration (a United Nations NGO), the article has this to say, “The International Organization for Migration (IOM), from the beginning of 2021 to date, has made it clear that the migration policy the EU is using is a total failure: too many deaths are recorded and too many people are missing. The EU has concentrated its funds in order to make Frontex a frontier giant, aimed solely at armouring the EU “fortress” and its borders, rather than rescuing lives.”

In its 2024 report ‘Crimes of the European Coast Guard Agency Frontex’, Sea-Watch focuses on activity in the Central Mediterranean where boats from Libya and Tunisia are tracked by Frontex planes and drones. The information they gather is not relayed to search and rescue ships in the area, but is forwarded instead to militias running the ‘Libyan Coast Guard’ who use it to intercept the boats and return people to Libya where they face violence, torture and forced labour, according to the UN, Human Rights Watch and other NGOs. In other words, Frontex uses its surveillance capacity not to support rescues, but rather to facilitate interceptions and ‘pullbacks’ of people in distress by violent militias who profit from their exploitation. In doing so it breaches both maritime and human rights laws.

Wanting to move away from all too visible pushbacks where Frontex is the key actor and which are damaging to the EU’s reputation, the agency’s work in Tunisia indicates the way things have been moving – that is, towards the externalisation of the EU’s borders. In June 2023 the EU Commission signed an agreement on ‘migration control’ with the Tunisian government under whose terms the EU pays Tunisia to stem the flow of people making for the sea and deport those it arrests at sea. This involves, amongst other measures, the funding of 6 coast guard vessels.

In October 2023 Statewatch, an organisation monitoring state activities that threaten human rights and civil liberties, reported the following, “…in Tunisia, the coast guard has been conducting pullbacks of people who have subsequently been dumped in remote regions near the Tunisian-Algerian border. According to testimony provided to Human Rights Watch, a group of people who were intercepted at sea and brought back to shore were then detained by the National Guard, who: ‘…loaded the group onto buses and drove them for 6 hours to somewhere near the city of Le Kef, about 40 kilometres from the Algerian border. There, officers divided them into groups of about 10, loaded them onto pickup trucks, and drove toward a mountainous area. The four interviewees, who were on the same truck, said that another truck with armed agents escorted their truck. The officers dropped their group in the mountains near the Tunisia-Algeria border, they said. The Guinean boy [interviewed by HRW) said that one officer had threatened, “If you return again [to Tunisia], we will kill you.’”

According to an article in the German publication Migazin in November 2023, crossings from Tunisia fell dramatically in the months following the signing of the country’s agreement with Frontex. This was due not only to increased coast guard activity but to other related factors, for example the expulsion of thousands of sub-Saharan Africans from the port city of Sfax to the Libyan and Algerian borders. The EU is also pressurising the Tunisian government to introduce visa requirements for neighbouring West African states.

Freedom of movement in the Schengen area would thus be protected at the direct expense of freedom of movement between African states.

MANAGING MIGRATION

Stripped back, Frontex’s job is first and foremost to ensure that immigration of cheap labour into the EU only takes place officially, for example through enlargement as when Bulgaria and Romania were admitted to membership in 2007. Its second remit is to keep asylum claims to a minimum. But it has to perform its role under the guise of protecting ‘European values’ of freedom and democracy – and thanks to some persistent journalists and monitoring organisations, this has become an increasingly precarious balancing act. Frontex’s response can be seen in part in the language of its 2024 Strategic Risk Analysis Report where, in what is a clear attempt to distance itself from the deportation of desperate people, it expands its role to include countering ‘emerging threats’ – while at the same time ‘upholding shared European values’ by developing ‘a proactive intelligence-led framework’.

One of the threats it has recently identified is ‘hostile geopolitics’, a term they use to refer to the use of migrants as political weapons. For example, during the refugee crisis on the Polish-Belarus border in November 2021, Belarus was accused, by NATO’s Secretary General Stoltenberg amongst others, of instrumentalising migration by inviting refugees into the country in order to push them across the Polish border, a charge categorically rejected by Belarus. Poland rejected the 3-4,000 migrants trying to cross the border, along with its EU treaty obligations to accept asylum seekers. But within a year it had accepted 3 million refugees from Ukraine without question.

The EU takes in large numbers of refugees from time to time, when it suits the purposes of its capitalists. Germany has twice in recent years taken in huge numbers to boost its workforce. But in 2015, when it took in 1 million refugees fleeing the war unleashed on Syria by the US, hundreds of thousands of other Syrians were forced to find illegal routes, and this influx caused a rapid acceleration of an ongoing review of EU’s immigration policy and the role of Frontex in policing the borders.

This in turn resulted in the adoption in June 2024 of the EU’s Pact on Migration and Asylum. The Pact’s provisions include the speeding-up of processing at borders and a far greater emphasis on deportation and arrangements with non-EU countries – externalisation again. The Pact is also designed to address disputes between EU countries affected differently by migration by replacing earlier mechanisms, like the ‘return to the country of entry’ requirement, with what they hope is a more equitable distribution of responsibilities and obligations; the inequities – for example between Italy and more northern countries – have been putting the Schengen Agreement itself under enormous pressure. This may be a forlorn hope however; according to the European Council on Refugees and Exiles, some member states are already demanding stricter measures.

Earlier this year, an Associate Director of the Migration Policy Institute research centre in Europe suggested, in an unusually frank assessment of the contradictions in EU migration policy, that the new Pact is both essential to containing the rise of far-right parties in the EU and a danger to the rights of migrants and asylum-seekers.

A further contradiction arises from the plan to expand Frontex’s technological capacities. The agency admits that increased border surveillance will lead to a corresponding increase in illegal border-crossings as more people try to get round the new controls, including increased document and identity fraud.

But the contradictions run much deeper than this.

WHAT SCHENGEN AREA?

A future full of “ominous scenarios and hybrid threats” leading to the “destabilisation of Member States” that Frontex conjures up in its public documents has another dimension it doesn’t mention. As guardian of the Schengen area, Frontex’s own future is called into question by the increasingly frequent suspensions of the Schengen Treaty. Temporary suspensions in certain circumstances are provided for, but France has had some restrictions in place since 2015 and has not removed further restrictions it imposed during the Olympic Games. There have been border controls in place since 2023 between Slovakia and Hungary, the Czech Republic and Switzerland and others.

Much more serious in terms of its implications was the suspension of the Treaty in early September 2024 by the weakened Scholz coalition in Germany. Freedom of movement into Germany is now halted with all nine countries on its borders in an attempt to shore up support amongst voters attracted by openly racist solutions to Germany’s economic woes offered by the far-right AfD. As reported in the Financial Times, “Interior minister Nancy Faeser said… that the move — an extension of existing controls on borders with four countries — is designed to ‘further restrict irregular immigration and protect us from the acute dangers posed by Islamist terror and serious crime… We will do everything to better protect people in this country.’” In an article published in El Pais on September 16th 2024, Gloria Rodriguez-Pina suggests this move will impact not just the nine countries sharing a border with Germany but the whole of the EU and the future of the entire Schengen Agreement. Poland’s PM Donald Tusk agreed, calling it a de facto suspension of the whole treaty.

If that weren’t enough, in mid-November the far-right Wilders coalition government in the Netherlands also announced it would suspend the Treaty from December 9th, taking advantage of violence created by Israeli football fans in Amsterdam to close its borders. In recent coalition discussions, the PVV (Wilders’s party) had not been able to persuade its partners to declare an asylum crisis and so was denied the opportunity to push through the full migration and asylum restrictions it wanted. Blaming the Amsterdam Moroccan community for what it called ‘pogroms’ against visiting Israeli Jews, Wilders was suddenly able to pursue his racist programme – he not only pushed through suspension of the Schengen Agreement but also threatened to immediately deport any dual nationality citizens found to have been involved in the violence.

PARADISE DISMANTLED

The Schengen Agreement is one of the main pillars of the EU architecture. If it cannot be shored up, the project totters. Leading figures have not been slow to recognise the looming problem and to understand the need to strengthen Frontex’s hand in securing the union’s external borders. If individual countries with centre-right governments under pressure, as well as far-right governments openly pursuing racist agendas, are not to take matters completely into their own hands, the Commission has to act. Enter Frontex’s call for the formation of ‘a grand policy on migration’.

In a speech at the Sorbonne in Paris on April 25th this year, facing political challenge from the right and from the left and just two weeks before calling the snap election, Macron saw it as expedient to stress the significance of the new Pact on Migration, “Sovereignty cannot exist without a border.… …this agreement enables us to improve control of our borders by establishing compulsory registration and screening procedures at our external borders, to identify those who are eligible for international protection and those who will have to return to their country of origin, while enhancing cooperation within our Europe.”

As part of her pitch for re-election this year as head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen also stressed the importance of collective borders and collective action against instrumentalised migration in her speech to the European Parliament on July 19th 2024 and said she would increase the number of Frontex officers to 30,000, “…we must also do more to secure our external borders. Our Eastern Border in particular has become a target for hybrid attacks and provocations. Russia is luring migrants from Yemen up north and pushing them deliberately against the Finnish border. We should always keep in mind that a Member State's border is a European border. And we will do everything we can to make them stronger. This is part of the reason why we must strengthen Frontex. To make it more effective, while fully respecting fundamental rights, I will propose to triple the number of European border and coastguards to 30,000.”

She went on to praise the new Pact – and to add a quick postscript about migrants being human beings, “The Migration and Asylum Pact is a huge step forward. We put solidarity at the heart of our common response. Migration challenges need a European response with a fair and firm approach based on our values. Always remembering that migrants are human beings like you and me. And all of us, we are protected by human rights. Many pessimists thought that migration was too divisive to agree on. But we proved them wrong. Together we made it.”

The contradictions in the Union are becoming not only visible but also unignorable. If the Schengen Agreement is falling apart as national economic exigencies take precedence over the free trade & movement area that created them, it is not only Frontex’s role that will be thrown into question. Without Schengen the identity of the EU itself becomes a problem. Over what exactly would the Commission then preside? It is interesting that at this critical point the Commission has at its disposal, if not the long-debated European army, a sizeable and expanding armed force with some of the characteristics of a standing army.

Paradise, it turns out, is being dismantled from within.

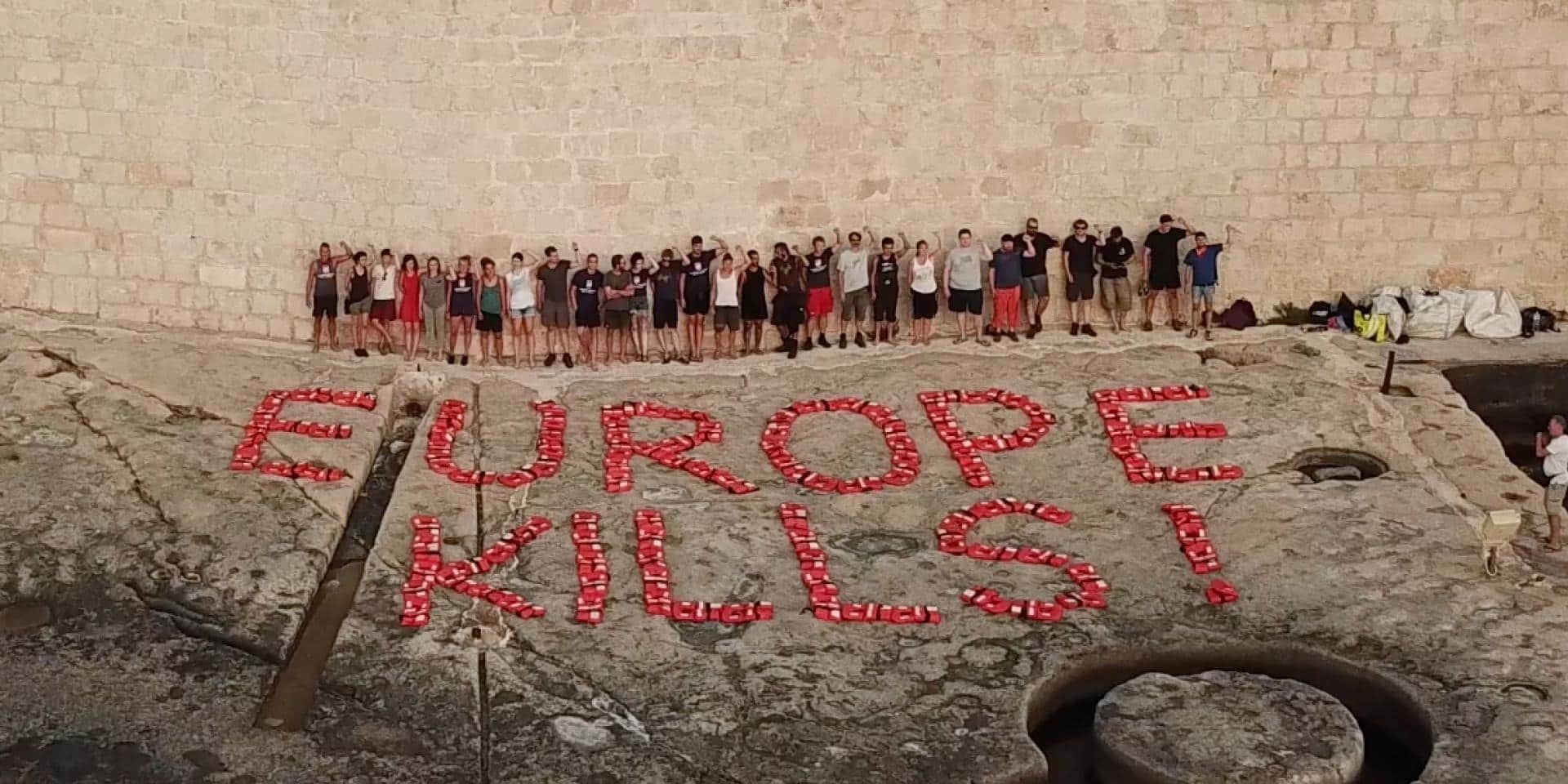

Sea-Watch protest

This is the world’s most lethal migrant route, “Instead of offering those seeking protection legal and safe routes, the borders are being turned into a human rights-free space and the Mediterranean into a mass grave,” Bérénice Gaudin

Refugee camp in Tunisia photo by Mohamed Ali Mhenni

Frontex ship photo by Fransesco Palacco