Inquiry into US and UK illegal war in Iraq

By Pat Turnbull

The Chilcot Report, 2.6 million words long, costing over £10 million, taking seven years, has already disappeared from the news. Sir John Chilcot’s statement on 6th July, the day of the report’s publication, seemed startlingly frank, especially to the many people who had been prepared for a whitewash. He described the 2003 invasion of Iraq as the first time since the Second World War that the United Kingdom had taken part in ‘an opposed invasion and full-scale occupation of a sovereign state’, and continued: ‘We have concluded that the UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted. Military action at the time was not a last resort.’

The action was undertaken by the US and the UK without United Nations Security Council approval. Sir John said: ‘In the absence of a majority in support of military action, we consider that the UK was, in fact, undermining the Security Council’s authority.’ He added: ‘…the circumstances in which it was decided that there was a legal basis for UK military action were far from satisfactory…The judgments about Iraq’s capabilities … were presented with a certainty that was not justified..

‘Mr Blair told the Inquiry that the difficulties encountered in Iraq after the invasion could not have been known in advance. We do not agree that hindsight is required…That brings me to the Government’s failure to achieve the objectives it had set itself in Iraq…More than 200 British citizens died as a result of the conflict in Iraq. Many more were injured…The invasion and subsequent instability in Iraq had, by July 2009, also resulted in the deaths of at least one hundred and fifty thousand Iraqis – and probably many more – most of them civilians. More than a million people were displaced. The people of Iraq have suffered greatly…In March 2003: There was no imminent threat from Saddam Hussain. The strategy of containment could have been adapted and continued for some time. The majority of the Security Council supported continuing UN inspections and monitoring.’

But now the sting in the tail: ‘Military intervention elsewhere may be required in the future. A vital purpose of the Inquiry is to identify what lessons should be learned from experience in Iraq.’

Yes, war is still on the agenda for the British ruling class. Theresa May, the newly appointed Prime Minister, could already be bold enough to answer “Yes” in the debate in the House of Commons on Trident on 18th July to the question whether she is prepared to cause the death of hundreds of thousands of innocent human beings. War is still on the agenda – only next time it will be fought better. Lessons will be learned and according to David Cameron some already have been. He has established the National Security Council, with a breadth of expertise and where everyone is free to speak their mind, which would have discussions, as he put it ‘if we take the difficult decision to intervene in other countries.’ He promised ‘we will still stand with our American allies when security interests are threatened. We can still rely on our intelligence agencies. It would be wrong to conclude our military are not capable of intervening successfully round the world. We should not conclude it is always wrong to intervene. There are times when it is right and necessary, for example against Daish in Iraq and Syria today.’

So it bears emphasizing what a disaster the Iraq invasion and occupation was, and the Chilcot Report contains plenty of evidence. The paragraph references are to the 150-page Executive Summary.

The UK was prepared to invade and occupy four provinces of Iraq, referred to as MND(SE), but was not prepared to take on the subsequent responsibilities, for example, to restore infrastructure already undermined by more than a decade of crippling sanctions and now destroyed by war. It was not ready to administer a state ‘where the upper echelons of a regime that had been in power since 1968 had been abruptly removed’.

As the Executive Summary says in Paragraph 593: ‘Throughout the planning process, the UK assumed that the US would be responsible for preparing the post-conflict plan, that post-conflict activity would be authorised by the UN Security Council, that agreement would be reached on a significant post-conflict role for the UN and that international partners would step forward to share the post-conflict burden.’

The sheer disregard for the population is demonstrated in Paragraph 642: ‘Faced with widespread looting after the invasion, and without instructions, UK commanders had to make their own judgments what to do. Brigadier Graham Binns, commanding the 7 Armoured Brigade which had taken Basra City, told the Inquiry that he had concluded that “the best way to stop looting was just to get to the point where there was nothing left to loot”.’ Paragraph 644: ‘The impact of looting was felt primarily by the Iraqi population rather than by Coalition Forces…’

Paragraph 682 describes ‘Food shortages and the failure of essential services such as the supply of electricity and water, plus lack of progress in the political process’ and, not surprisingly, ‘attacks on UK forces in Majar al-Kabir in Maysan Province on 22 and 24 June’.

Paragraph 820 on Resources gives the picture:

‘*The direct cost of the conflict in Iraq was at least £9.2 bn (the equivalent of £11.83bn in 2016). In total, 89 percent of that was spent on military operations.

*The Government’s decision to take part in military action in Iraq was not affected by consideration of the potential financial cost to the UK.

*The controls imposed by the Treasury on the MOD’s budget in September 2003 did not constrain the UK military’s ability to conduct operations in Iraq…

*…Some high-priority civilian activities were funded late or only in part.’

The UK was instead concentrating on withdrawal from not long after the invasion. One reason is given in Paragraph 720: ‘In June 2004, the UK had made a public commitment to deploy HQ ARRC to Afghanistan in 2006, based on a recommendation from the Chiefs of Staff and Mr Hoon, and with Mr Straw’s support. HQ ARRC was a NATO asset for which the UK was the lead nation and provided 60 percent of its staff.’

Paragraph 721: ‘It appears that senior members of the Armed Forces reached the view, throughout 2004 and 2005, that little more would be achieved in MND(SE) and that it would make more sense to concentrate military effort on Afghanistan where it might have greater effect.’

No wonder therefore that (Paragraph 757) ‘After visiting Iraq in early May [2006], Air Chief Marshal Sir Jock Stirrup, Chief of Defence Staff … identified the risk that UK withdrawal from Basra would be seen as a “strategic failure” and suggested that “astute conditioning of the UK public may be necessary” to avoid that.’

Paragraph 792: ‘The Iraq of 2009 certainly did not meet the UK’s objectives as described in January 2003: it fell far short of strategic success … deep sectarian divisions threatened both stability and unity … exacerbated [by the Coalition’s] decisions on de-Ba’athification and on demobilisation of the Iraqi Army and were not addressed by an effective programme of reconciliation.’

Paragraph 796: ‘By 2009, it had been demonstrated that some elements of the UK’s 2003 objectives for Iraq were misjudged. No evidence had been identified that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, with which it might threaten its neighbours and the international community more widely. But in the years between 2003 and 2009, events in Iraq had undermined regional security, including by allowing Al Qaida space in which to operate and unsecured borders across which its members might move.’

In view of this damning conclusion, some humility might be expected. But no: new Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson is already stating that more regime change, the removal of President Bashar Al-Assad, is the necessary precondition to ending the civil war in Syria.

Then there are the questions the Chilcot Report does not go into: what right do two of the most highly armed nations in the world - both with nuclear forces, both having engaged in recent decades in aggressive military actions against nations far from their own shores - have to impose on any other nation weapons inspections, economic sanctions, no-fly zones and military attacks, giving themselves the right to tell another nation what type of armaments it is allowed to possess and invade and occupy it on those grounds?

The Chilcot Report, with its detailed analysis and particularly its transcripts and even filmed interviews, gives people the unusual opportunity to have an insight into the business of prominent representatives of all areas of the British state. The report’s conclusion, that the war was unjustified, offers the added interest of seeing different departments and different individuals vying to absolve themselves of responsibility. One of the most chilling aspects of the report, however, is how glibly war is included in all calculations.

Jeremy Corbyn in his speech in Parliament in the debate on Chilcot, described the invasion as an act of military aggression, a catastrophe, a decision based on flawed intelligence. But he also pointed to all the people who got it right, the one and a half million in Britain, the tens of millions across the world who demonstrated to oppose the war. All of these people and many more are needed now to prevent another, worse war than the Iraq War of 2003.

"The government's decision to take part in military action in Iraq was not affected by consideration of the potential financial cost to the UK."

"The direct cost of the conflict in Iraq was at least £9.2bn (the equivalent of £11.83bn in 2016). In total 89% of that was spent on military operations."

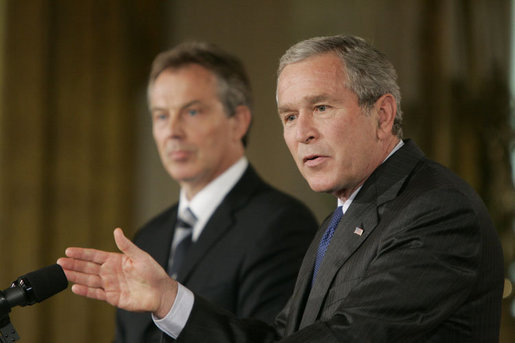

Partners in war crimes Tony Blair and George W Bush