COPS and Robbers in the Climate Crisis

by Brian Durrans

“[…] international cooperation is the only way humanity survives global heating”

Opening address by Simon Stiell (UN Climate Change Executive Secretary) to world leaders at COP29, Baku, Azerbaijan, 12 November 2024. (1)

Much has been, and continues to be, argued about the climate crisis/emergency, not least by socialists and other increasingly concerned citizens. This article attempts an initial overview from a socialist perspective, linking climate crisis and the challenge of controlling it to some other class-related problems in our tumultuous world. Worrying about the climate crisis prompts too few to action and too many to disengagement, but whilst the evidence and comparisons considered below acknowledge real concern, they also allow cautious optimism.

CLIMATE TARGETS

The landmark treaty known as the Paris Agreement on Climate Change was ratified in 2015 by 196 parties of the United Nations (195 member-states and the EU) and passed into international law a year later. Its signatories are bound by the treaty’s obligations, initially designed to limit the rise of the global average temperature to within 2⁰C above pre-industrial levels during the 21st century. Since then, it has become clear that missing an even lower target of 1.5⁰C increase, risks more severe droughts, heatwaves and rainfall than earlier supposed, with potentially devastating consequences for millions of lives and livelihoods, especially among those already struggling to survive. Some of these consequences could be irreversible, impacting on and jeopardising not only our successors but even life itself.

To confine global warming within a 1.5⁰C increase (averaged over the final decade or longer), global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will need to peak before the end of next year and reduce by at least 43% by 2030 and to net zero by 2050. Net zero is an ambiguous term referring to offsetting any further greenhouse gas emissions by measures generically described as carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS). Although such measures seem to have little to offer in the short term, they are sometimes included in the prospective toolkit after 2030; and in any case focusing on carbon dioxide emissions - the main form of the carbon - leaves other gases such as methane out of the frame. There is, however, a big difference between capturing carbon as CO2 already in the atmosphere, in existing, protected or extended “sinks”, such as oceans and wetlands or forests, and using or storing it through a technological fix instead of releasing it into the air. This is especially so when the technology has yet to be fully developed at least at the required scale, and with an appropriately low supply chain carbon footprint and cost to users. In the meantime, CCUS is under suspicion as a potential alibi for the primary polluting fossil fuel industry to undermine the Paris Agreement.

SNAPSHOT OF CLIMATE OPTIONS

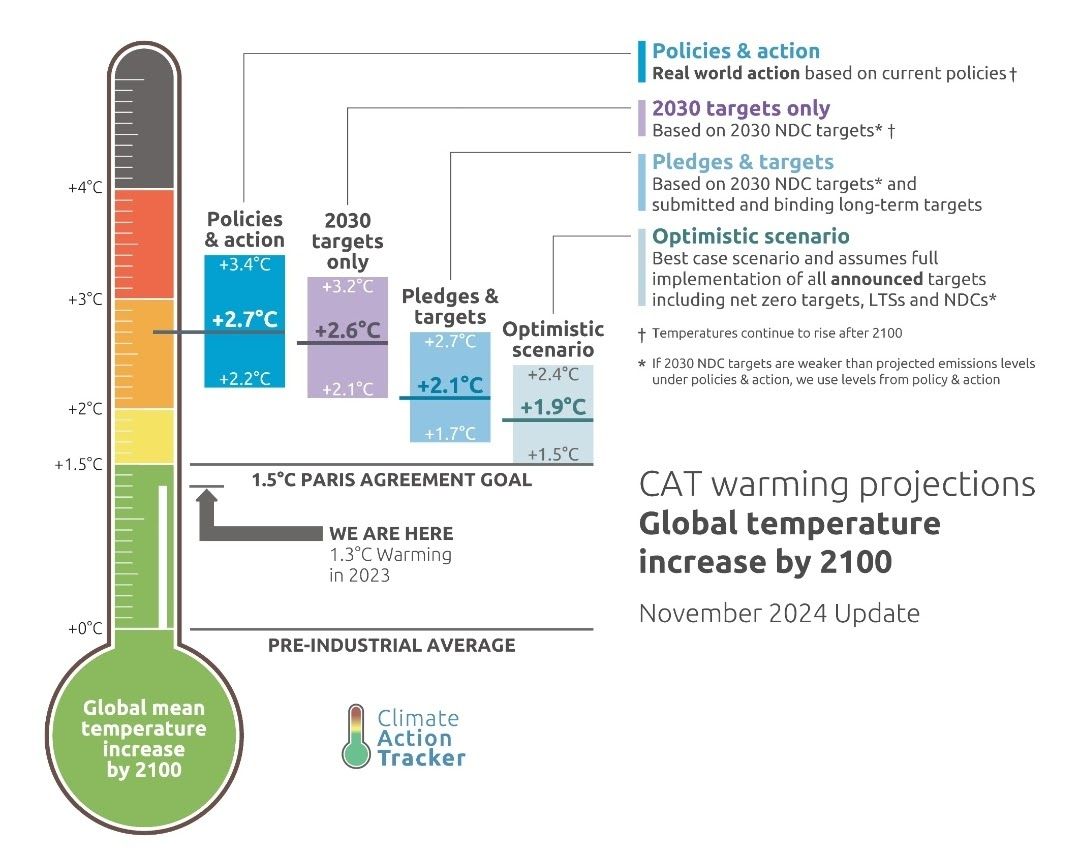

Climate Action Tracker drew up the accompanying chart shortly before COP29 (11-22 November 2024) to project likely increases in future global warming according to actions or pledges taken to control it. (2) It is a stark reminder that existing policies, even with improvements so far promised, will probably miss the recommended 1.5⁰C target by the end of this century.

The chart, like other similar ones, is both a criticism of missed opportunities and an increasingly urgent reminder to do better. But it is also, and importantly, a powerful expression of organised understanding, with the potential to help overcome the problem it addresses.

Recognising why average temperature measurements matter so much is the outcome of an unprecedented scientific collaboration across the world. Based on the pioneering work of meteorologists and other specialists, including influential contributors in the Soviet Union, the global perspectives on climate and ecosystems (that is, life support systems) which have been developed since then have informed the Paris Agreement and every subsequent COP. The arresting scientific insight is that whilst global warming is ultimately the most systemic threat to life on Earth, it is already pushing fragile sub-systems to their limits. If interlocking patterns of winds, rainfall, pollination, ocean currents and other phenomena continue to diverge sharply from those on which human, or any, life depends, then when any of them collapses, others will swiftly and automatically do the same.

CAPITALISM AND THE CLIMATE CRISIS

While investigating the ailing ecosystem to monitor the developing problem and find ways to control it, this same collaborative scientific enterprise found its cause was industrial capitalism (3) and the crisis it caused now puts capitalism in a dilemma. We might expect its continuing drive for profits – “business as usual” – to impede a solution to global warming and ecosystem collapse, but no business can operate in conditions unable to support life. Capitalism will either adapt accordingly or be the death of us. On current evidence, humanity can’t afford to wait for the collapse of capitalism before fixing the climate problem. Startling as it may seem, there is, however, a precedent for this sort of question.

HOW TO DEFEAT A GLOBAL THREAT

Faced with Axis fascism in the late1930s, nations of very different politico-economic systems united to defeat it. The unity that clinched victory in the Second World War and the huge benefits of winning it hold important lessons for the present fight to save the planet. That victory in 1945 came at an appalling price. Millions of lives could have been saved if an anti-fascist alliance had been formed earlier to defeat Franco in Spain, or eject the invading Japanese from China, or later, as requested of its Western allies in 1942 by the beleaguered USSR, to distract some Nazi forces from their race to Moscow by opening a second front.

Today’s battle against climate change can draw two lessons from this experience.

First, whilst it may be better to act sooner rather than later, or even later rather than too late, mature statecraft will be necessary if less urgent or lower priority differences are to be shelved in favour of the unity capable of defeating a larger, shared or more imminent threat.

Second, once a shared, existential threat has been neutralised through co-operation between different countries or socio-economic systems, the differences earlier set aside to help it happen, might, in the afterglow of that shared achievement, no longer seem so intractable as they did before. Take the United Nations, for example.

he UN came into being in the wake of the Second World War, and its present composition and functions have inevitably been shaped by a variably divided world’s legacy of advances, defeats and compromises. For its current role of leading the world against the climate crisis to succeed, those nations most responsible for the historical rise of global warming will need to make the biggest contribution to reduce it, while those with least responsibility who are among the most vulnerable, deserve sufficient protective compensation, not only to save lives but also to uphold the principle that the UN is the body for all its members, whom it treats with equal respect. As this example suggests, a success for the UN against the climate crisis would be a success for all of humanity; but for that to happen, the UN will need to resist current attacks from the US and its allies and undergo progressive reform so it can fully represent the global interest. Serious discussion of such a development is already beginning, though not specifically focused on climate. (4)

Whether or not those changes happen soon, or the world somehow muddles through the crisis with the help of a UN not yet in the best shape, and whether we win the climate battle decisively or by the skin of our teeth, the climate emergency already puts the geopolitical order in the spotlight and any order that might emerge in a newly-sustainable world would certainly be an enhanced version of the UN itself.

In the wake of overcoming the climate crisis, such a body could do the same with war and poverty and even begin to facilitate a global transition to socialism, at least by denying capitalist elites the option of blowing everyone up in an attempt to hold onto power.

Securing any future – let alone that promising scenario – will be up to what is done in the next few years.

WESTERN CAPITAL'S RESPONSIBILITIES

The Climate Action Tracker chart expresses the present challenge in statistical terms. The final report of the meeting in Baku had to say something about the commitment of COP29 to quantify the contributions and compensations meant to help solve the climate crisis by bridging the huge gap between the rich, polluting West and the poor, barely polluting South. Eventually poorer nations were, as they saw it, railroaded into accepting a package of £300bn for this from wealthy nations up till 2035. This was an increase of $50bn on what was previously on the table, but well short of the $500bn which the G77 group of developing nations wanted and there was a great deal of anger expressed by representatives of those countries at the end of the summit. At least the G20 meeting that took place in Rio de Janeiro agreed that taxing extreme personal and corporate wealth could help what COP29 was simultaneously grappling with in Baku.

Another reminder of the complex and dirty politics of climate mitigation is that drastically reducing emissions from fossil fuels is both the single most effective way of reaching 1.5⁰C by 2100 and the most contested, above all by the oil industry, which is preponderantly though not all Western. This nets a couple of red herrings.

The US and some of its allies extract and sell their own fossil fuels (mainly oil and natural gas) on a huge scale, which adds considerably to global warming. This has supported their own industrial base since at least the 19th century. More recently developing countries, such as India and China, and to a lesser degree Russia, use or extract fossil fuels to develop their own industries and have therefore also contributed to GHG emissions, but have been doing so for a shorter time. Since their own economies have invested heavily in renewable energy (China is by far the biggest producer, user and exporter of solar panels), their emissions have begun tailing off as required under the Paris Agreement and are set to meet its target goals.

China’s unprecedented success in lifting more people out of absolute poverty than has ever been achieved anywhere now places it, at least for its Western critics, alongside South Africa as a “middle income” country. As they see it, this makes China liable to pay proportionately more towards helping low-polluting, highly climate change-vulnerable nations, almost all of them former colonies of Europe, which would also reduce the bill to which the far longer-polluting West would be liable.

Such arguments illustrate how UN bodies have always operated in terms of geopolitics (see note 4). The question of the appropriate levy on China diverts attention from both the reluctance of the historically primary polluters of the wealthier West to pay their due and, above all, from the status of compensation as a pivot of the Paris Agreement itself.

PULLING OUT ALL THE STOPS

This article has reviewed a few of the options and challenges facing the attempt to solve the climate crisis at the level of UN-co-ordinated actions and monitoring. As well as member-states, corporations and smaller businesses and their lobbyists, scientists, NGOs and global and local civil society actors have skin in the game and hugely variable control over outcomes.

It’s time to pull out all the stops. The climate justice movement has the potential to influence and leverage opinion in the heartlands of the capitalist West, especially if it can highlight and mobilise inclusively around climate change as a vital issue for the working class. Geopolitics and capitalist interests currently obstruct progress but if they can be mitigated, so might the crisis itself.

(1) The recent COP29 was the 29th Congress of Parties, the UN’s system of updating and monitoring progress towards globally-agreed climate control measures: https://unfccc.int/news/worsening-climate-impacts-will-put-inflation-on-steroids-unless-every-country-can-take-bolder

(2) https://climateactiontracker.org/documents/1277/CAT_2024-11-14_GlobalUpdate_COP29.pdf. CAT helpfully summarises the significance of the information displayed in this chart (glossary: NDC=national declared climate [target]; LTS=Long-Term [low GHG emissions development] Strategy).

(3) https://monthlyreview.org/2022/11/01/anthropocene-capitalocene-and-other-cenes-why-a-correct-understanding-of-marxs-theory-of-value-is-necessary-to-leave-the-planetary-crisis/?mc_cid=a54dc7f8d4&mc_eid=6ae113ca2f.

(4) https://richardfalk.org/2024/11/08/how-can-the-un-be-liberated-from-geopolitics

Speakers at COP29 photo by Vice Presidential office of Brazil

Faced with Axis fascism in the late1930s, nations of very different politico-economic systems united to defeat it. The unity that clinched victory in the Second World War and the huge benefits of winning it hold important lessons for the present fight to save the planet

The US and some of its allies extract and sell their own fossil fuels (mainly oil and natural gas) on a huge scale, which adds considerably to global warming. This has supported their own industrial base since at least the 19th century.