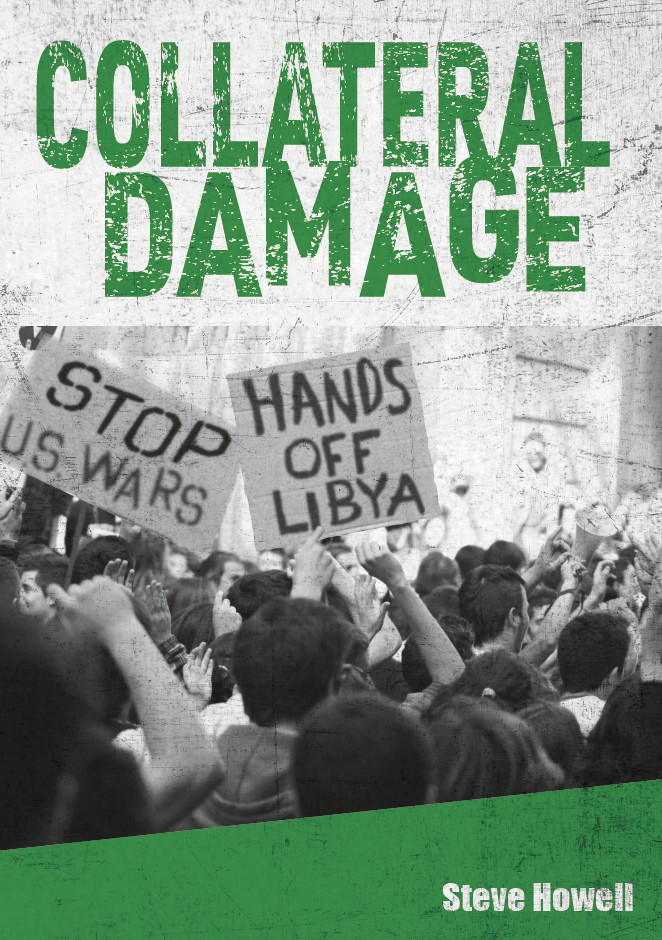

Collateral Damage - Book Review

August 2021

Review by Pat Turnbull

Steve Howell’s novel Collateral Damage is set in 1987, a year after the United States bombed Libya on April 14 1986. The attack, involving at least 44 F-111 bombers, was launched from bases in Britain. In the novel Ayesha, a central character, remembers standing in Aldeburgh on the Suffolk coast with her fiancé Tom, watching the planes fly overhead on their deadly mission. The purpose of the attack was to assassinate Libyan leader Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. It failed, but destroyed his home and killed his little adopted daughter. In the novel Ayesha later visits this destroyed home, just as Tom had done a few days before his death. The search for the truth of how Tom died is the central plot of the novel.

In 1986, only the US, Britain and Israel supported the attack on Libya, in contrast to 2011, when a United Nations Security Council resolution gave the green light for the destruction of Libya in a seven-month NATO bombing campaign involving 11 countries.

SEARCH FOR THE TRUTH

Tom is a member of a delegation from the UK which has gone to Libya to a conference marking the first anniversary of the bombing. On the visit he is found dead on a beach next to the hotel where the group is staying. The opening chapter is Tom’s funeral, then the book goes back eight days to what has led to this point. Jed attends the funeral. He has been drawn into the story by his ex-girlfriend, Hannah, a close friend of Ayesha. Ayesha does not believe Tom’s death was an accident, as they have been told, and Hannah wants Jed, who is a lawyer, to help her investigate what happened. The quest will take Jed and Ayesha to Libya, and to discoveries about the British state which, while little surprise to Ayesha, open Jed - and Hannah’s - eyes to a scary scenario.

It’s Jed’s first funeral and his first personal encounter with death. Ayesha at the age of 34 can count 27 people she has personally known who have died. Jed sees Ayesha as ‘someone who defies prediction and appears to act on impulse’ though her actions ‘usually have, he’s discovered, an inner logic’. This is our introduction to Ayesha, a vivid presence in the book, shaped by experiences all too common for people from the Middle East like herself, but unknown to young British people like Jed. Ayesha is someone who scans the room when she enters a café, and sits with her back to the wall. Her mother is Palestinian, and her father Lebanese – otherwise she would be stateless. She has come to Britain to study, sponsored by her aunt, leaving Beirut after the Israeli invasion in 1982. Her friend Hannah says, ‘When she first came here from Beirut she was in a really bad way.’ This is something we learn more about during the book. Anyone knowing something about recent Middle East history will feel a shiver of foreboding when they hear that she taught girls in the Shatila Palestinian refugee camp.

We also learn more about Jed’s father who, his mother tells him, ‘got himself into serious trouble for doing what he thought was the right thing’. She tells Jed this because she is worried he is getting himself into something with similar results. This opens the story up to another angle on the US’s baleful role in the world, post Second World War.

We often see events from Ayesha’s point of view. At the airport on the journey to Libya, Jed says, “Your French was impressive.” Ayesha’s answer: “That’s colonialism for you.” When she finds Jed has a US as well as a UK passport she says, “So, you have two of the most sought-after passports in the world.” When Jed says, “It feels like we’re on the run,” we are told that ‘Ayesha nearly says she’s felt like that for five years.’ When they are travelling through Tripoli, Ayesha is reminded how long it is since she has been in an Arab city.

Edward Chamberlain, who is accompanying Tom’s father, retired Major Carver, to Libya to see Tom’s body and make arrangements for its return, is the representative of the British state. When Ayesha says of the non-aligned movement “Libya does have some friends”, Chamberlain replies, “And a lot of them not at all desirable.” His view of Tom’s participation in the delegation: “Tom was misguided in coming here in the first place, and his family are suffering the tragic consequences.” His advice to Ayesha and Jed: “If you choose to stay in Tripoli, you do so at your own risk.” No wonder, as one of the Libyans tells Ayesha and Jed, the Libyan Foreign Ministry is “worried about how the British could make trouble for us internationally.” Ali, their Libyan diplomat companion, and Chamberlain are ‘serving different masters with a big imbalance of power.’

Later in the book we get to know O’Brien, the head of the law firm where Jed works, who came to London from Derry to study in the 1950s and worked in a Law Centre ‘helping Irish families fight Rachmanite landlords and cowboy contractors’. Now he deals with immigration and nationality issues. It’s lucky for Jed that this shrewd and likeable lawyer has an idea how to deal with the British state and its representatives.

REAL EVENTS

This is an exciting and enjoyable novel, with engaging central characters, which deals with matters rarely tackled in UK fiction, and usually not from the standpoint of people like Ayesha. It is also a whodunnit which gradually reveals the truth in true whodunnit fashion. I won’t say more because I hope everybody will read it and enjoy it as much as I did!

There is, however, an extra link to real events which Steve Howell reveals in a blog of 13 April 2021 entitled, How an unexplained death influenced Collateral Damage. The book’s cover description of the author tells the reader: ‘…as an activist in the peace movement, he attended a conference in Tripoli in 1987 to mark the first anniversary of the US air strikes on the city, an experience that influenced Collateral Damage.’ In his blog Steve Howell says: ‘A Canadian journalist, 31-year-old Christoph Lehmann-Halens had been found dead on the ground next to the hotel. He was a peace activist who also worked for the Southam News Agency in Ottawa….To this day Lehmann-Halens’ death is a riddle.’ Steve Howell adds this, about his book: ‘I hope, in an indirect way, it contributes to the memory of Christoph Lehmann-Halens, and the cause of peace for which he worked.’