Charter cities will impoverish the working class

By Clare Bailey

William Blake would recognise a charter city. Published in 1794, his poem London opens with lines that record the suffering of people living in a city owned and operated by commerce in the interests of profit:

I wander through each charter’d street

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

Charters were active everywhere in 18th century England, conferring rights on wealthy corporations at the expense of everyone else. Thomas Paine had much to say about them in The Rights of Man: “Every chartered town is an aristocratical monopoly in itself… …[charters] are sources of endless contentions in the places where they exist, and they lessen the common rights of national society… …[a man’s] rights are circumscribed to the town, and, in some cases, to the parish of his birth; and all other parts, though in his native land, are to him as a foreign country.”

The loss of rights under the charters in Paine’s time find their mirror image nowadays in the experiences of workers in special economic zones (SEZs) across the world, where national laws and rights are suspended and companies operating in them are more or less free to do as they please. SEZs – sometimes referred to as ‘open zones’ – take different forms; freeports and charter cities are both forms of SEZ.

In 2009 the American economist Paul Romer, who coined the term charter cities, described them as new cities with special rules operated by foreign governments. The first attempt to establish one of these private cities in Honduras in 2012 was resisted by the local population, whose lands would have been appropriated, and the scheme finally collapsed under the weight of corruption evident at every level of the process. Madagascar, Rwanda and El Salvador have also been targets of this kind of experiment. Initially involving foreign government participation, the idea of the charter city has developed into a “a public-private development partnership between the host country government and a private developer”, according to the Charter Cities Institute (CCI) – echoes of the early colonial methods of the East India Company, one of the first corporations to be granted a charter by Elizabeth I.

Charter cities are a flexible concept, adaptable to country and context, and are often linked in reports and discussion papers to problems posed for capital by refugees and migration, problems which can also be opportunities missed according to Dr Mark Lutter, founder and board member of the CCI. He sees establishing charter cities – he calls them “Prosperity Cities” – in existing refugee camps as “a politically attractive proposition”, which would not only provide a cheap source of labour but would also alleviate migration-related concerns of European countries by “reducing refugee flows”. Bingo.

DRIVING DOWN WAGES

In charter cities wages would follow the reality of existing SEZs, in the Philippines for example, where they are far lower than wages nationally. The CCI Governance Handbook explicitly states that “lower income people are the primary target residents” of charter cities and that wages in charter cities should be pegged at 20-40% of the national average, where the national average is already very low.

In the UK this would mean garment workers in Leicester currently earning £4 an hour would be earning the right sort of money for companies setting up manufacturing plants inside a charter city. Leicester is inside the recently designated East Midlands Freeport and, looking at it through the charter city lens, the long-term failure of all responsible agencies to enforce UK labour law and the minimum wage in the city’s garment industry begins to look less like poor coordination and a lot like an experiment in a hitherto unofficial SEZ in the UK.

Freeports are SEZs where normal tax and customs rules do not apply and companies based inside them are free to add-value to imports, goods may then be processed and re-exported without paying tariffs or taxes. Eight new freeports were created in the 2021 budget: East Midlands, Felixstowe, Humber, Liverpool, Plymouth, the Solent, the Thames, and Teeside. Though the UK has experimented with freeports since the mid-1980s, these new versions are much more extensive and the ambitions for their role in the UK economy much higher. Freeports are not only mini tax havens. Len McLuskey in 2021 called them “sinkholes, draining decent jobs and wages away from our communities.” They will “sidestep employment rights, minimum wages and basic standards”.

Charter cities would go even further. The Charter Cities Institute envisages that the cities would in most cases develop their own banking systems, though it recommends frankly that they should not try to develop a healthcare system because public health is too complex and too expensive for any insurance model to work. The Institute is talking about charter cities in the Global South but the model is clearly transferable and is being transferred.

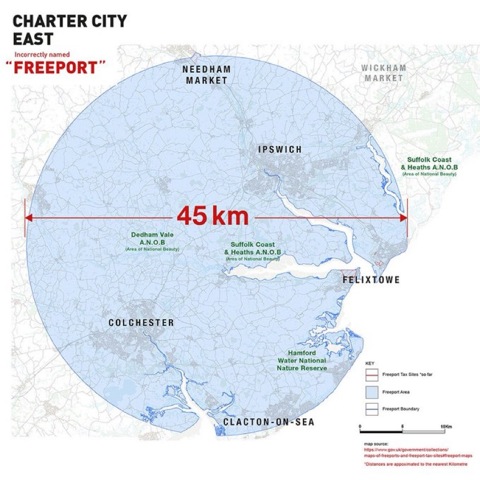

While there have long been SEZs of different kinds in the big capitalist economies, there has yet to be a fully-fledged charter city experiment. Watchers of the freeport system in the UK are wondering whether it is about to take place here. Some already argue that the new freeports are to all intents and purposes charter cities – as in the image below which shows the extent of the Felixstowe freeport area, that is the area inside which depots, warehouses, assembly plants etc can be established. The Amazon warehouse in Tilbury falls within the boundary of the Thames freeport.

Questions are being asked about what is happening in Liverpool and whether a charter city experiment is taking shape there. In July this year, Liverpool City Council voted to abolish the role of directly elected mayor and to return to a leader and cabinet model with much greater direct accountability from May 2023. In response, on August 19th the government moved effectively to take over the running of the city. On the same day, the Liverpool Echo reported the appointment of a commissioner to “oversee the authority's financial management and to transfer the council's governance and financial-decision making to the commissioners along with powers over recruitment.” A “strategic advisory panel” will develop a long-term plan to “shape the future of the city”. Peel Ports – a land-hoarding infrastructure company involved in innumerable scandals and controversies and already criticised heavily for wielding excessive influence on development in Liverpool – is no doubt standing by.

Less than a week later, ahead of a Tory leadership hustings visit to East Anglia, Liz Truss had this to say: “If elected prime minister, I will turbocharge the economies of places like Norwich, Great Yarmouth and across East Anglia by unleashing the private sector with tax cuts and better regulation, cracking down on strike action slowing our economy, and repealing the EU regulations that do not work for our rural communities.”

The Felixstowe dockers have had something to say about that prospect.

Image by Stan Fontan