A woman's struggle against fascism

By Ruth Selwyn

This is a small part of the story of a person’s life. I shall call her Sarah.

She was born in 1917 and grew up in the East End of London, an only child but part of a very large extended family. Her mother and several of her aunts worked in the garment industry, and at least three of them had been involved in a strike of garment workers.

She joined the Communist Party very young – probably when she was seventeen. One of her aunts also joined about the same time. She vividly remembered the battle of Cable Street, when Mosley attempted to march his fascists through the East End. She and a friend were chased by a mounted policeman down the steps of a ladies’ lavatory. She feared the horse would stumble on the steps and fall on top of them. Fortunately it kept its balance, and she and her friend locked themselves in the cubicles until the policeman gave up and went away.

Soon after this, CP headquarters sent for Sarah and told that she was needed to train in the Soviet Union. She went, telling her mother that she was going to Paris.

Near Moscow she, along with other similar volunteers from various countries, was trained as a radio operator. The volunteers all had pseudonyms, and for security reasons were not allowed to know each others’ real names. The radios they used were small, and easily dis-assembled. The various parts were made to look like parts of a sewing set, or a manicure set. Once trained, she was sent to Spain, which at the time was in the middle of the civil war, and billeted on a farmer and his wife behind the Fascist lines. There she regularly sent and received radio communications. She was one of a cell of four which was managed by a particular General, whose name she did not tell me, and knew nothing beyond that. She said that the farmer’s wife looked after her like a daughter, although my mother couldn’t speak Spanish. This was deliberate: if she were interrogated by a non-English-speaking person, she couldn’t give anything away.

Once, a fascist plane came flying over the fields towards the farmhouse, strafing as it went. She leaned out of the window, shaking her fist and shouting. The farmer’s wife pulled her in and admonished her severely. It was too dangerous.

The general in charge of her cell betrayed them. What happened to the other three members she never knew, and assumed they had been executed. There was no way to search for them, because she never knew their real identities. She was saved by another general, who smuggled her across the French border as his daughter. Being black-haired and dark-eyed, she could pass for a Spaniard. Being a general, he was able to get her out of Spain with no papers, no passport.

Later, in the beginning of the war, in London, Sarah continued to operate her clandestine radio, each night assembling and then dis-assembling it.

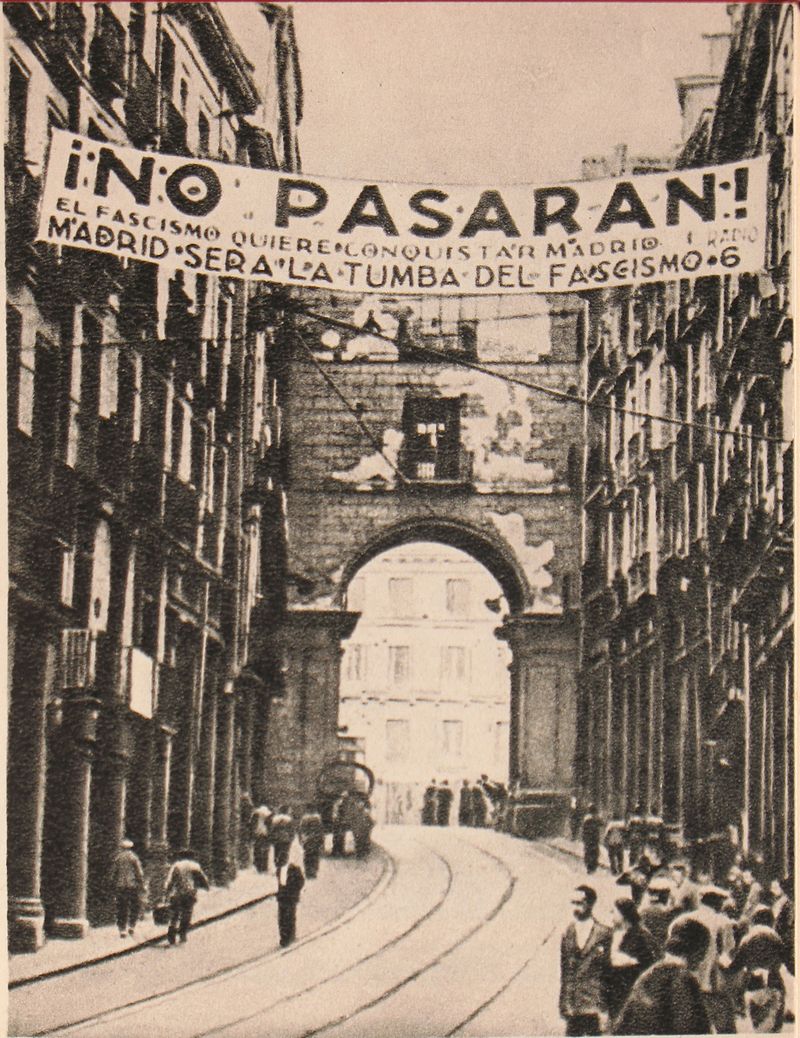

1936-39: A Republican anti-fascist banner in Madrid which reads, 'Madrid shall be fascism's grave'.