West's dangerous view of North Korea

This article is also available as a Podcast. Click on the link at the end of the article to listen.

By Simon Korner

Here’s a typical western headline on North Korea: “‘Mentally unstable’ North Korean leader Kim Jong-un threatens war after being pushed over the edge by US ‘fat’ jibes” (Daily Mirror, 29/2/17). Here’s another, more middle-class, just as biased: “With or without Donald Trump's help, Kim Jong-un could easily plunge the planet into its third world war inside a century.” (Independent 30/4/17). And here’s Stop the War’s Lindsey German (14/8/17): “Trump and Kim are both highly unpredictable, making them a danger to us all.” This view, almost universally accepted now, including on the Left, that North Korea and the US are equal dangers to the world, is a distortion. It ignores the balance of world forces and the still-living effects of the Korean war.

The current crisis cannot be understood without an appreciation of that terrible conflict and how it shaped the North Korea of today. A pamphlet I Saw the Truth in Korea by Alan Winnington, Daily Worker correspondent and one of only two western journalists to report the war from the Northern side, records what he witnessed. For his pains, he had his passport confiscated by the British government and never returned to the UK, ending his days in East Germany. Winnington describes a visit to the shallow graves dug just after the infamous Daejon Massacre of some 7,000 civilian prisoners by US-led forces. This massacre, ordered by Syngman Rhee, the South Korean US puppet and former collaborator with the Japanese, was one among many other murders of political prisoners by the regime in South Korea in the first months of the war – 100,000 were killed, according to US Embassy official Gregory Henderson. Winnington put the figure at 200,000 at least, and as high as 400,000.

Meanwhile, north of the 38th Parallel – a line drawn without consultation by two American junior officers in the closing days of World War 2, using a National Geographic map of Korea to arbitrarily divide Korea into north and south. In North Korea in 1945, a democratically elected government, headed by Kim Il Sun, who’d led a guerilla army against the Japanese occupiers since 1932, brought in women’s emancipation, land reform, nationalization of industry, subsidized rice, free healthcare, schools and universities built, and a huge expansion of literacy. Today, North Korea’s health system is the envy of the developing world, according to the WHO.

Soviet troops withdrew in 1948, after failing to persuade the US to withdraw jointly.

US 1950 INVASION OF NORTH KOREA

Winnington makes the point very clearly that it was America that invaded Korea in 1950, not the other way round: “At dawn, on Sunday, June 25, the South Korean Army — American trained, American equipped and with American officers as advisers… — crossed the Parallel at three points after a two-day artillery preparation…By three o’clock in the afternoon, the North Korean People’s Army had pushed them back and was going over to the offensive...

Like trained seals, the entirely illegal body which calls itself the United Nations Commission in Korea had sent to America that Sunday afternoon a document purporting to prove that the North Koreans had begun the attack. Their evidence consisted only of a statement made by the South Korean Government and Syngman Rhee.”

During the war, the US dropped almost half a million bombs on Pyongyang alone. Napalm was widely used, 32,500 thousand tons of it, forcing the population to live underground, and germ warfare was used. Bombing of dams destroyed rice production and led to starvation. Hospitals and schools were systematically destroyed. General MacArthur ordered that “every installation, every facility, and village in North Korea” should become a military target. More US bombs were dropped on North Korea than the US had used in Asia during the whole of World War Two.

Chief Justice William O. Douglas visited Korea in the summer of 1952: “I had seen the war-battered cities of Europe; but I had not seen devastation until I had seen Korea…,” he said.

The war totally destroyed 18 out of the North’s 22 cities. General LeMay wrote: “We burned down just about every city in North Korea and South Korea both… we killed off over a million civilian Koreans.” Current estimates of the total deaths vary. 2.9 million civilian dead is generally accepted by western sources, not including 1.5 Korean and Chinese soldiers, and 54,000 US soldiers. 20% of the North’s population was killed. Such a traumatic experience explains the North’s deep suspicion of America ever since and its fiercely patriotic stance. This is not a question of brainwashing, but of experience in living memory.

The war ended with a ceasefire but no peace treaty, in 1953. This was regarded as a victory by the North, simply for having survived. According to the Agreement no reinforcements or weapons could be introduced into Korea. In 1958-9 the US deployed nuclear missiles in South Korea.

THE CURRENT SITUATION

There are 28,500 US troops stationed in South Korea, with 50,000 more in Japan. $3.1 billion was spent on reinforcing US forces in South Korea in 2012 alone. Three aircraft carriers, the USS Ronald Reagan and the USS Theodore Roosevelt and the USS Nimitz, are patrolling the area, each the centrepiece of a strike group of destroyers and other heavily armed warships. A nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Michigan, with 154 nuclear-capable Tomahawk missiles on board, is docked in Busan.

During its series of almost continuous drills throughout 2017, US and South Korean B1-B strategic bombers and F-35B Stealth fighters flew right up to the border – performing “simulated precision strikes against North Korea’s military facilities,” according to the U.S. Pacific Command and South Korea’s Defense Ministry. These exercises practice pre-emptive “decapitation” raids aimed at eliminating the leadership in Pyongyang.

Heightened rhetoric has accompanied the drills. Trump told the UN in September 2017 that he would “totally destroy” North Korea, if necessary, and said Kim Jong Un and his foreign minister “won't be around much longer” if they ever develop a nuclear missile capable of reaching the USA. The threats of annihilation are not new. In 1995, Colin Powell said the US would turn North Korea into a “charcoal briquette”. Kim has responded in kind, but in a David and Goliath situation the rhetoric is also unequal.

Having once been obliterated in war, Korea takes threats seriously and has developed its own nuclear deterrent and missiles, with 22 missiles launched in 15 tests. It now has between 20 and 30 nuclear bombs, and can build at least 7 more a year. Retired Russian general Viktor Yesin estimates it will take 4-5 years for them to be able to hit American cities, and maybe 3 years to hit US bases in the Pacific. Once it can reach the US, it will have attained deterrence, and can then scale back its conventional forces.

The US has not started evacuating the 125,000-140,000 American civilians from South Korea – so clearly war is not imminent. But in the current standoff, accidents are a real danger. There are no rules of engagement for air encounters. So if the North scrambled fighters to intercept US planes, even if it had no intent to engage, the potential for an accidental collision is high. There have been accidental clashes before – the last one in 2001 was off the coast of China, but then the tension was lower.

How likely is the US to make a pre-emptive strike in future? The development of the new B61-12 nuclear bomb, which can penetrate the earth’s surface and destroy North Korea’s weapons buried underground, may strengthen the hand of those voices pushing for military action – powerful figures such as retired 4 Star general General Jack Keane and the former Ambassador to the UN John Bolton.

Keane says the US was weakened by allowing China and North Korea to believe no military action would happen. Thus, the job now was to shake that belief and “put the military option back on the table.”

“How much do you fear a nuclear weapon?” asked John Bolton. “That’s the question. We have to look at preemptive military action.”

But the hawks in Washington are constrained by public opinion. A Washington Post-ABC News poll found that 67% of respondents opposed pre-emptive US strikes on North Korea and agree to military action only if Pyongyang were to attack the United States or one of its allies.

Admiral Dennis Blair former Director of National Intelligence said in a telling interview: “… what we’ve learned over time is, it matters who starts these things, right? When you get the US public behind an administration, it’s when we’re attacked. Pearl Harbor is a classic example... So, what you want to do in most of these situations is manoeuvre the other guy into taking the first step, and then you crush him after he started it.” He cites the 2003 invasion of Iraq as an example of what not to do.

Another problem for the US is the difficulty of intercepting intercontinental ballistic missiles. Philip E. Coyle III, who ran the Pentagon’s weapons-testing program, believes the anti-missile system “is something the US military, and the American people, cannot depend upon.” So if the US provoked a war, Seoul and other cities would be destroyed. And if Seoul were sacrificed as the price for destroying North Korea, Japanese trust in the US protective umbrella would be lost. The American system of alliances in Asia would be over.

On the other hand, the price for not acting is loss of credibility. If Trump’s threats remain empty, the whole US edifice of military threat appears hollow and weak. And credibility is becoming increasingly important to the US in relation to its diminishing power in the world.

So the question is: how long can its provocation go on, without action? What action could it take? It is possible that US rhetoric could force its hand – and US public opinion may be turning in Trump’s direction, infected by the feverish war propaganda. A poll – of Republicans, note – showed 46% supporting pre-emptive action. Some action does seem possible, on a fabricated pretext – calibrated so as not to provoke a full war but to show, like the mother of all bombs in Afghanistan, and the Cruise missiles attack on the Syrian airbase, that it means business. This would obviously be an extremely dangerous tactic.

So, apart from a risky covert raid to assassinate the North Korean leadership – something the South Koreans, under defence minister Han Min-koo, are rehearsing, with a special brigade – what are the more immediate US options?

Cutting off food and fuel. This is already underway, with a 30% cut in oil supplies to North Korea, and a total ban on the North’s textile exports – its second-biggest earner and providing a livelihood for at least 100,000 workers. Further sanctions applied in December 2017 tightened the net.

While sanctions won’t bring down Kim Jong Un, they will create misery for the population – in a form of collective punishment. The US hopes this will eventually destabilise the government or lead to internal splits. Sanctions are nothing new, of course. Since the Korean war, the North has been the most heavily sanctioned country in the world. But now sanctions are strangling it, with the majority of its export earnings having been blocked.

80% of North Korean land is mountainous and imports are needed to feed the population, so depriving North Korea of foreign exchange will as Mike Whitney in Counterpunch argues, “weaponise” food. According to the 38 North website, which monitors the country using North Korean defectors, “the 2017 growing season has been very challenging for North Korean agricultural producers…. The impact of further sanctions… will likely bring further challenges to the situation in North Korea.”

Other countries bullied into imposing sanctions include India, the Philippines, Mexico, Peru, Egypt and Uganda.

Many African countries, such as Namibia, had warm relations with North Korea, dating back to liberation struggles. But now the US has forced them to cancel contracts with North Korea. Treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin said: “North Korea economic warfare works.”

Other US restrictions focus on China – in particular, threatening to cut off China’s access to the US financial system. Ed Royce, chairman of the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, said the US could give Chinese banks and companies “a choice between doing business with North Korea or the United States.”

CHINA

So, what about China’s response to these threats, as North Korea’s oil supplier and main trading partner? Though it is growing in strength and confidence, China is still too weak for war with America. It fears the growing US presence in Asia, and is now facing the deployment of the Terminal High-Altitude Air Defence (THAAD) system in South Korea. This is a first-strike weapon, aimed at China as much as North Korea.

Despite its reluctance, if the US attacked North Korea, China would be forced to act. It could not let the US bomb its neighbor with impunity or allow US forces up to its border. But it might try to limit the scale of its response to avoid full-scale war. Hence its interests for now are to try to de-escalate and play for time, to remove the US pretext for flooding Japan and South Korea with new arms. Is agreeing sanctions caving in to US pressure? Yes, and one can see the reason, but a sharper response might be more effective.

If US threats to North Korea are aimed at China, they also threaten Russia too. Russia, like China, shares a land border with North Korea, very short, and Vladivostok, a strategic port city and headquarters to Russia's Pacific Fleet, is only about 100 km from this border.

Russia-North Korea trade is growing, doubling in the first quarter of this year – mostly supplying energy. Putin has said he understands the North’s position. They “know exactly how the situation developed in Iraq,” he said recently. “They know all that and see the possession of nuclear weapons and missile technology as their only form of self-defence. Do you think they’re going to give that up?”

Both Russia and China have called for de-escalation and a “double freeze” – the simultaneous suspension of North Korean missile tests and US/South Korean military drills. But the US has refused, demanding denuclearization upfront – in effect, telling North Korea to disarm as a precondition to any talks.

SOUTH KOREA

What is South Korea’s position? Apart from preparing for covert raids on the North, the South claims it can produce a bomb that can paralyse North Korea's power systems, the ‘blackout bomb’.

But the South Korean population wants peace, and has come out clearly against the deployment of THAAD. And business has been hit by the Chinese anti-THAAD boycott of tourism and other trade.

President Moon Jae-in told the UN General Assembly: “All of our endeavors are to prevent the outbreak of war and maintain peace… We do not desire the collapse of North Korea. We will not seek unification by absorption or artificial means.” Moon’s recent election was a setback for the US.

As for Japan, so far it has not shot down the North Korean missiles flying over its airspace – so clearly we’re not at that stage yet. But Abe is using the crisis as a reason to boost Japanese rearmament, and his recent re-election strengthens his hand against Japan’s popular peaceful constitution.

BRITAIN

Britain for its part would not support a US pre-emptive strike - having learned from the Iraq war, which not only finished off New Labour but did not provide the hoped-for windfall of lucrative oil contracts, which all went to America.

Boris Johnson said recently: "Maximising diplomatic and economic pressure on North Korea is the most effective way to pressure Pyongyang to halt its aggressive and illegal actions." On the other hand if the US provoked North Korea into action, Britain could be drawn in as a NATO ally. According to the Royal United Services Institute, Britain would provide high-tech satellite communications and reconnaissance, and anti-submarine T-23 destroyers against the North Korean navy.

As for Germany, Angela Merkel warned that "only a peaceful diplomatic solution to this conflict is possible. Anything else would lead to catastrophe, I am deeply convinced of that."

Similarly, Macron said that France “will oppose any escalation” in Korea, and Le Monde commented, “For the rest of the international community, [Trump’s] speech [to the UN] is a terrible challenge.”

US DRIVE TO WAR

To conclude, for North Korea, nuclear weapons are existential in nature. It will never give them up, because it knows what happened to Iraq which had none, and to Libya after it gave up its nuclear programme. The US sanctions are only hurting the 25 million North Koreans, but will not alter the country’s fundamental self-defence posture. The only rational way forward is a peace treaty – allowing for mutual deterrence, the way mutually assured destruction kept the peace during the Cold War.

The 1994 agreement between the US and North Korea was working – until Bush tore it up and included North Korea in the “Axis of Evil”, making it a target of regime change, with Obama continuing the drive to war, and now Trump. In January last year, North Korea offered to “sit with the US anytime” to discuss de-escalation. In May 2017 it offered to stop nuclear testing and missile launches if the US would end drills and sanctions, and sign a peace treaty ending the Korean War. But the US refused to talk. It won’t permit any smaller state to defy its world hegemony. The latest North-South dialogue around the Winter Olympics is viewed by the US State Department as an attempt to “drive a wedge” between Washington and Seoul.

The economic value of the US military-industrial complex has risen 31% so far this year, on the S&P 500 index. In Trump’s first week of office alone, when he promised to raise spending by $54 billion, share prices in the defence and aerospace sector jumped 6.8%. The Korea crisis is producing huge dividends for shareholders as Japan and South Korea buy extra high-tech military equipment. Trump’s cabinet – the so-called ‘adults in the room’ of generals Mattis, McMaster and Kelly, along with CIA director Pompeo – represents a visible manifestation of the military-industrial establishment. Trump’s famous unpredictability is not a personal trait but a deliberate establishment tactic to impose a climate of uncertainty and fear on the rest of the world.

So, what can we do here? We need to counter the liberal propaganda which blames Kim along with Trump, to clarify who the main enemy is. This in effect, like the condemnation of Assad, promotes and prolongs war, rather than inhibiting it. We need to help get an anti-war Labour government elected and, remembering that Clement Attlee sent 100,000 soldiers to fight the Korean war, maintain pressure for peace after that. And we need to try to drive a wedge between Britain and the US, by pressing for an end to the dangerous and destructive “special relationship”.

North Korea's Museum of American War Atrocities.

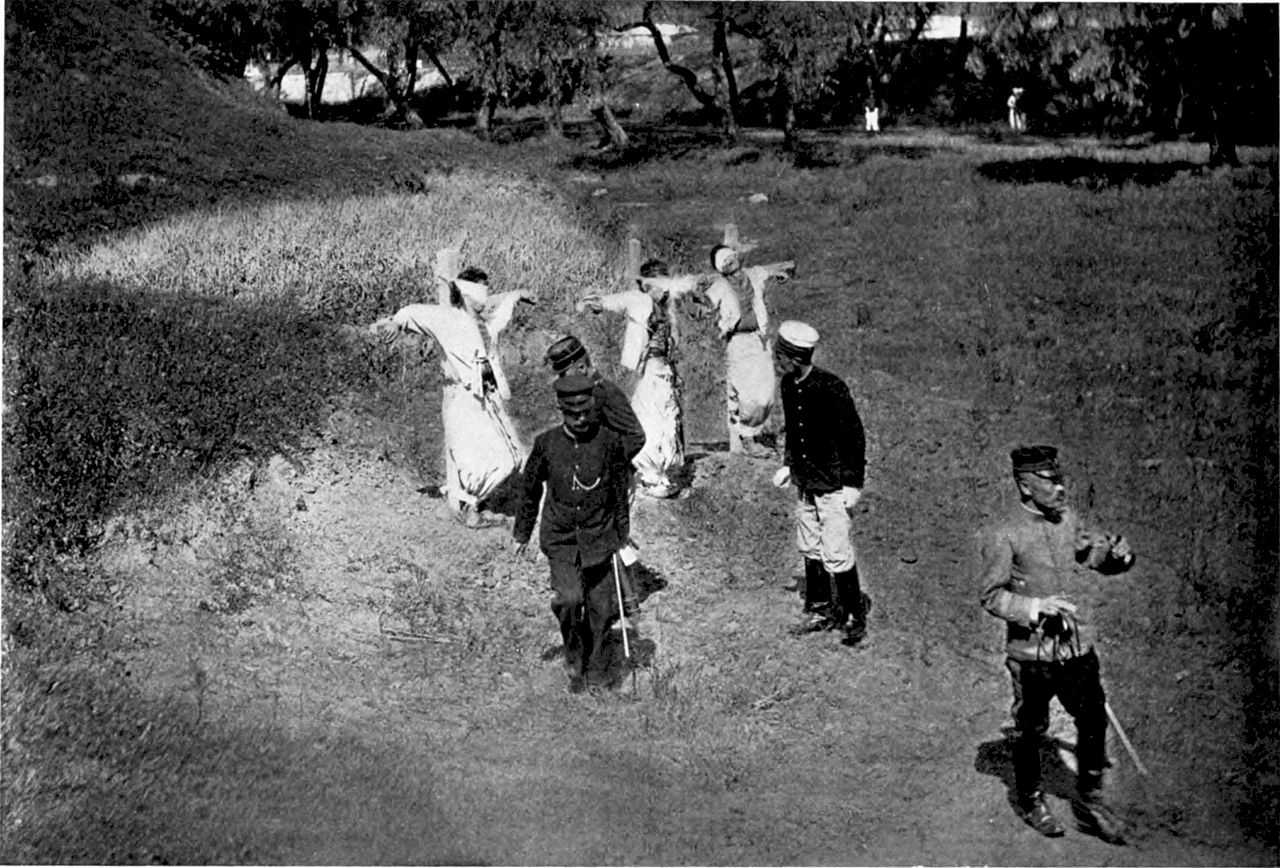

Three Koreans are executed for resisting the Japanese occupation (1910-45) of Korea.

May 1948: Korean Communists await execution during the period of the US occupation (1945-48) of South Korea.

A dental clinic at Pyongyang Maternity Hospital.

the recent election of Moon Jae-in as South Korea's President was a setback for the US.

Kim Jong-un

Donald Trump