W. E. B. Du Bois - Black American thinker and activist

Pat Turnbull delves into - The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing my Life from the Last Decade of its First Century - International Publishers in 1968. All quotes are from the book.

At a time when the deaths of black Americans at the hands of the police have prompted the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, it is timely to remember Dr W.E.B Du Bois, one of the greatest black Americans.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in 1868. As he writes in his autobiography: ‘The year of my birth was the year that the freedmen of the South were enfranchised, and for the first time as a mass took part in government. Conventions with black delegates voted new constitutions all over the South, and two groups of labourers – freed slaves and poor whites – dominated the slave states. It was an extraordinary experiment in democracy.’ By the time he died in Accra, Ghana, in 1963, he had welcomed socialist revolutions in Russia and China, and the end of colonialism in many of the countries of Africa.

The black Burghardts were descended from Tom, born in West Africa, kidnapped as a child by Dutchmen, who grew up as a slave or serf in the family of white Burghardts. Tom’s service in the American Revolutionary War freed him and his family, and the Bill of Rights of 1780 declared all slaves in Massachusetts free.

EDUCATION AND COLLEGE LIFE

Du Bois was the first in his family to finish high school. Everyone else at his school in Great Barrington, New England, was white, and he had almost no experience of colour discrimination. Not more than 50 in a population of 5000 were black. In 1884, aged seventeen, he went on a scholarship raised by a group of local churches to Fisk University, a black college in Nashville, Tennessee: ‘I was going into the South; the South of slavery, rebellion and black folk…I was thrilled to be for the first time among so many people of my own colour…A new loyalty and allegiance replaced my Americanism…There were men and women who had faced mobs and seen lynchings; who knew every phase of insult and repression.’ In a letter home to his pastor in February 1886 he wrote: ‘Some mornings as I look about I can hardly realise that they are all my people; that this great assembly of youth and intelligence are the representatives of a race which twenty years ago was in bondage.’ Du Bois says: ‘No one but a Negro going into the South without experience of colour caste can have any conception of its barbarism.’ At Fisk he began his writing and public speaking, and edited the Fisk Herald. He conceived of a plan: ‘I was determined to make a scientific conquest of my environment, which would render the emancipation of the Negro race easier and quicker… Knowledge and deed, by sheer reason and desert must eventually overcome the forces of hate, ignorance and reaction.’

Graduating from Fisk in 1888, he gained a scholarship to Harvard, where his lodging for four years was with a woman from Nova Scotia – ‘a descendant of those black Jamaican Maroons whom Britain deported after solemnly promising them peace if they would surrender.’ In 1892 he gained his master’s degree and went on to study at Berlin University from 1892 to 1894. There his understanding of scientific research developed, as did his view of the world. ‘I began to see the race problem in America, the problem of the peoples of Africa and Asia, and the political development of Europe as one. I began to unite my economics and politics.’ He was attracted to the socialist movement and attended meetings of the Social Democratic Party.

Aged 26…’after two long years I dropped suddenly back into “nigger”-hating America’ but ‘my Days of Disillusion which followed were not enough to discourage me.’ After receiving his doctorate from Harvard and teaching for two years at Wilberforce University, he accepted a temporary appointment at the University of Pennsylvania as ‘assistant instructor’ in sociology, and here he undertook the task of making a study of the desperate circumstances in which black people lived in what he described as, ‘the corrupt, semi-criminal vote of the Negro Seventh Ward’ in Philadelphia. As he writes: ‘I made a study of the Philadelphia Negro so thorough that it has withstood the criticism of 60 years.’ His study of two centuries of history, based on 5000 personal interviews and using libraries and private collections of black Philadelphians, was published in 1899. ‘It revealed the Negro group as a symptom, not a cause; as a striving, palpitating group, and not an inert, sick body of crime; as a long historic development and not a transient occurrence.’ But he was offered no further work. So in 1896 he joined Atlanta University to take charge of the work in sociology and organise conferences on the problems of black Americans. In his 13 years there he organised a series of annual publications containing a scientific study of their conditions of life. He describes Atlanta University as ‘a green oasis in a wide desert of caste and proscription, amid the heart-hurting slights and jars and vagaries of a deep race-dislike.’ He knew his people faced ‘terrific odds’. The studies he produced were so good they gained world-wide scholarly attention, and he took an exhibition to the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, where the exhibition received a Grand Prize and he as its author a Gold Medal.

NO DETACHED SCIENTIST

Du Bois’s work was disrupted, however, by two considerations: ‘one could not be a calm, cool and detached scientist while Negroes were being lynched, murdered and starved; secondly, there was no such definite demand for scientific work of the sort that I was doing, as I had confidently assumed would be easily forthcoming.’ One case exemplifies that problem: in 1906 he undertook a social and economic study, from the earliest times documents were available, of Lowndes County, Alabama, a former slave state with a large black majority. The study was commissioned and paid for by the US Bureau of Labour, but was not published, since, he was told, it “touched on political matters”. When a year later he asked for it back, he was told it had been destroyed!

Du Bois was also fighting ‘a new racial philosophy for the South’ in regard to education. College training was discouraged for the “child race” – black people ‘must be a humble, patient, hard-working group of labourers’. Only black leaders and institutions supporting this limited view received funding and support from capitalist ‘philanthropists’ in the North like Andrew Carnegie. At the same time the disfranchisement laws between 1890 and 1910 which had been passed by all the former slave states and quickly declared constitutional by the courts robbed black Americans in those states of the vote.

So, seeing a different way to pursue his aims, in 1910 Dr Du Bois gave up his position at Atlanta University and became Director of Publications and Research for the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), which conducted a highly effective campaign against lynching and mob rule. Du Bois’s Niagara Movement, founded in 1906, had declared: ‘We want the laws enforced against rich as well as poor; against Capitalist as well as Labourer; against white as well as black.’ It now merged with the NAACP, and in 1910 Du Bois started The Crisis, of which he was editor until 1934. This journal, aimed at black Americans, grew rapidly until by 1918 over 100,000 copies were published and sold. Du Bois also organised a series of Pan-African Congresses attended by black Americans, West Indians and Africans, in various European and US cities between 1919 and 1927, and in this last year made his first visit to Africa, representing President Coolidge at the inauguration of President King of Liberia.

Between 1918 and 1928 he made four trips to Europe, which he describes as ‘of extraordinary meaning’. The First World War, the Russian Revolution and the anti-Russian interventions of Britian, France and the United States, led him to read Karl Marx for the first time: ‘I was astounded and wondered what other areas of learning had been roped off from my mind in the days of my “broad” education.’ His visit to the Soviet Union in 1926 made a deep impression: ‘Never before had I seen so many among a suppressed mass of working people – people as ignorant, poor, superstitious and cowed as my own American Negroes – so lifted in hope and starry-eyed with new determination, as the peasants and workers of Russia.’

In 1934 disagreements with the mainly conservative board of the NAACP and restrictions on his freedom of expression as editor of The Crisis led him to leave the organisation and take up a post as head of the Department of Sociology at Atlanta University where he also published the journal Phylon for four years, and introduced as one of his three courses one on communism: ‘I was convinced that no course of education could ignore this great world movement.’ He was still attempting to promote the systematic study of the condition of black Americans, as a preparation for remedial measures, organising a plan of research in a network of black land-grant colleges with the black universities of Howard, Fisk and Atlanta at the centre. This was adopted on June 12, 1942, with Dr Du Bois as its official coordinator – and then, with no notice, Du Bois was suddenly retired from his post at Atlanta, which, as he says ‘savoured of a deliberate plot’. And thus was ‘a great plan of scientific work killed at birth’ and the study of the conditions of black Americans increasingly passed into the hands of Southern whites.

After another period with the NAACP (he was dismissed in 1947 after disagreements with the secretary), Dr Du Bois joined the Council on African Affairs as vice chairman. In the pre-Second World War witch hunt against progressive organisations in the USA, the Council had been put on the Attorney General’s list of ‘subversive’ organisations. This was a sign of things to come.

TRIED FOR CAMPAIGNING FOR PEACE

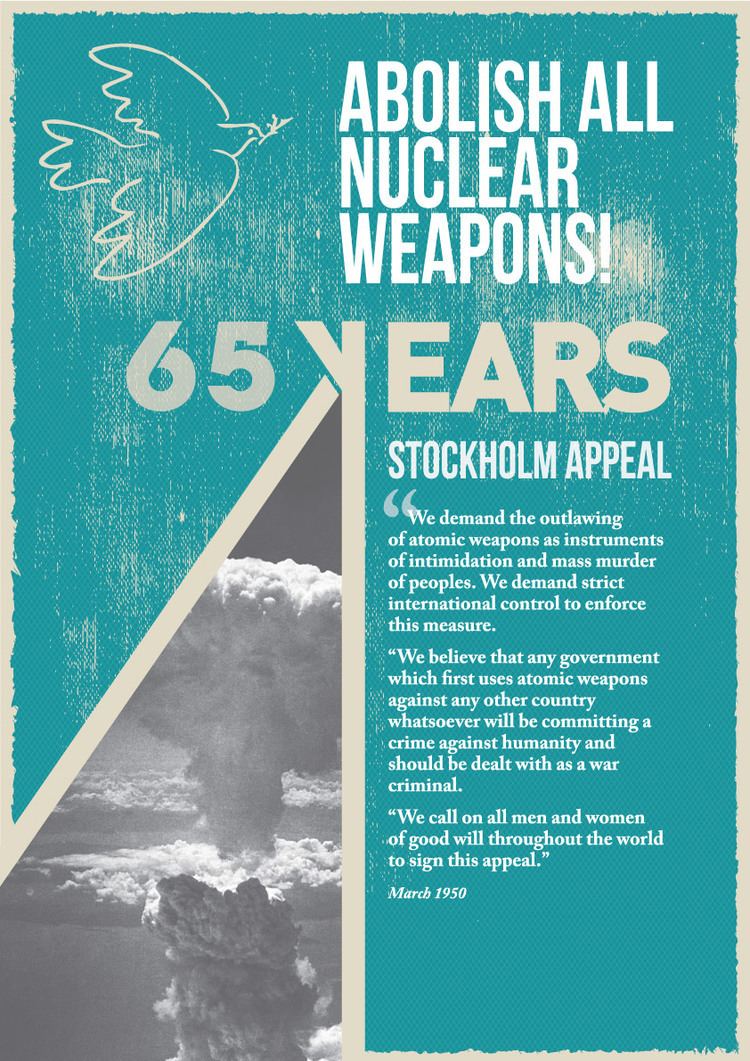

Du Bois had long been connected with the movement for peace. In The Crisis as early as 1913 he wrote: ‘The modern lust for land and slaves in Africa, Asia and the South Seas is the greatest and almost the only cause of war between the so-called civilised peoples.’ Now, in the period after the Second World War, he attended a series of important international peace meetings including what he describes as ‘the greatest demonstration for peace in modern times’ in Paris in April 1949. In four days witnesses from nearly every country in the world spoke for peace’. Du Bois himself spoke against colonialism and the threat of a Third World War. At the close of the conference, 500,000 French people filed through the stadium calling for ‘Peace, no more War!’ In August 1949 Du Bois addressed the 1000-strong all-Soviet peace conference in Moscow, the only one of 25 Americans invited to accept the invitation.

Back in the United States he formed the Peace Information Centre which circulated the Stockholm Appeal to abolish the atom bomb. The Centre collected 2,500,000 signatures – world-wide half a billion people signed the appeal. In July 1950 US Secretary of State Dean Acheson attacked the “Stockholm resolution” as “a propaganda trick in the spurious ‘peace offensive’ of the Soviet Union.” Speaking at the August 1950 meeting of the World Congress of the Defenders of Peace in Prague, Du Bois said: ‘It has become almost impossible today in my country, even to hold a public rally for peace.’ In August 1950 the Department of Justice demanded that the Peace Information Centre register as “agents of a foreign principal”, the implied ‘foreign principal’ being the Soviet Union. The organisation did not do so; in February 1951 Dr Du Bois was indicted by the Grand Jury in Washington as a criminal for “failure to register as agent of a foreign principal”. The Centre felt it had no option but to dissolve. It was clear that this act was intended to intimidate and silence all advocates of peace, and that the indictment against Dr Du Bois in particular was, as he puts it, ‘a needed warning to all complaining Negroes’. An International Committee in Defence of Dr Du Bois and his Colleagues was formed. Funds were collected from ordinary Americans to meet the costs of the case. Dr Du Bois and his wife Shirley Graham went on a lecture tour starting in June to explain the case and collect funds. Amongst other things Dr Du Bois said in his speech: ‘Why is it, with the earth’s abundance and our mastery of natural forces…that nevertheless most human beings are starving to death, dying of preventable disease and too ignorant to know what is the matter, while a small minority are so rich that they cannot spend their income? That is the problem which faces the world, and Russia was not the first to pose it, nor will she be the last to ask and demand answer.’

When the trial started in Washington in November 1951, Du Bois faced the possibility of five years’ imprisonment, a fine of $10,000 and the loss of his civil and political rights as a citizen ‘representing five generations of Americans’. For nine months the Department of Justice had tarred the organisation as agents of the Soviet Union and promised overwhelming proof of guilt. It never came. Dr Du Bois was acquitted. The Department of Justice had found no credible evidence despite visits by the FBI to anyone associated with the Peace Information Centre, even those who had only been to a meeting. Dr Du Bois also felt that the increasing support from ordinary black Americans, especially as the trial approached, and the fear of the repercussions on the black vote played a role in the verdict.

COMMUNISM

When Dr Du Bois finally received a passport in 1959, he went on a long tour, including the Soviet Union and China. On a visit to a conference of Asiatic and African writers in Tashkent, Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, he was surprised to find his work known to many delegates, and adds: ‘We saw and heard of men whose works are read by millions, and yet whose names most of us Westerners had never heard.’ On his visit to China, Dr Du Bois writes: ‘I have seen the world. But never so vast and generous a miracle as China, a nation with a dark-tinted billion. I have never seen a nation which so amazed and touched me as China in 1959.’ In a speech delivered in Ghana by his wife Shirley Graham on his behalf – he was in the care of a Soviet sanatorium – he advised Africa not to accept ‘the capital offered you at a high price by the colonial powers’ and instead to ‘compare their offers with those of socialist countries like the Soviet Union and China’.

In his autobiography W.E.B. Du Bois has a short chapter entitled ‘Communism’. He says: ‘I believe in communism’ describing it as ‘a planned way of life in the production of wealth and work designed for building a state whose object is the highest welfare of its people and not merely the profit of a part.’ He reflects: ‘Once I thought that these ends could be attained under capitalism – I now believe that private ownership of capital and free enterprise are leading the world to disaster.’ He concludes: ‘I know well that the triumph of communism will be a slow and difficult task, involving mistakes of every sort. It will call for progressive change in human nature and a better type of manhood than is common today. I believe this is possible, or otherwise we will continue to lie, steal and kill as we are doing today.’

W. E. B. Du Bois circa 1911

...in 1910 Dr Du Bois gave up his position at Atlanta University and became director of Publications and Research for the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), which conducted a highly effective campaign against lynching and mob rule.