US progressives buoyed by mid-terms, but big battles lie ahead

by Steve Howell

Hopes of ousting Donald Trump in the 2020 US presidential elections were buoyed by last November’s midterm elections that saw sweeping gains for the Democrats, including a strengthening of progressive representation in Congress and at state level.

The elections were the most comprehensive test of political sentiment in the US since Trump defeated Hillary Clinton in 2016. All 435 seats in the House of Representatives, 35 of the 100 Senate seats, 36 state governorships and thousands of state level posts were up for election.

In the battle for the House of Representatives, the Democrats gained 40 seats to win a clear 235-199 majority. Cumulatively in these contests, the Democrats won 58m votes to 50.5m for the Republicans, their largest midterm margin of victory since Watergate and a big advance on the 2016 presidential election when Hillary Clinton – though she lost in the electoral college - won the popular vote by a 66m to 63m margin.

The Senate elections were problematic for the Democrats. There was less scope for gains because Republicans were the incumbents in only nine of the seats up for grabs, and some of the seats the Democrats were defending were vulnerable because they were in states Trump won strongly in 2016. The upshot was the Democrats made only two gains but lost contests in four states they had previously held, including Florida where their margin of defeat was only 0.2% after a recount. Among those re-elected to the Senate was Bernie Sanders, who retained his Vermont seat with 67% of the vote.

In the gubernatorial contests, the Democrats made seven gains, including in the crucial Midwest battleground states of Michigan and Wisconsin, which had both been narrowly won by Trump in 2016. The Democrats did not, however, make a breakthrough in Georgia or Florida, where the votes were so close the Democratic candidates, Stacey Abrams and Andrew Gillum, challenged irregularities and did not concede defeat until more than a week after polling day.

ATTEMPTS TO FIX THE VOTE

The elections were widely marred by attempts to thwart voter registration, queues at under-resourced polling stations and candidates with unfair advantages in terms of money and power. The civil rights movement ensured that the 1965 Voting Rights Act required states with a history of discrimination to get federal approval before they could change voting laws. But, in 2013, the US Supreme Court voted 5-4 to rescind that provision of the Act, giving a green light for states to adopt rules – such as mandatory voter ID – that have the effect of suppressing turnout.

In Georgia, the Republican opponent of Abrams for Governor, Brian Kemp, was at the same time in charge of organising the election. Four days before polling, he had to be instructed by a federal court to give voting rights to more than 3,100 people who were incorrectly flagged as ‘noncitizens’ because the state failed to update their status. On election day, there was chaos at many polling stations because there weren’t enough machines for the numbers turning out to vote. At one, veteran civil rights leader Jessie Jackson appeared to urge people not to give up.

In Florida, recounts are mandatory in elections where the margin of victory is under 0.5%. With this applying in the contests both for Governor and a Senate seat, the sitting Republican Governor claimed there was ‘rampant fraud’ in two Democrat counties and sent law enforcement officers to investigate in a crude move to prepare the ground for a challenge if the recounts changed the result. Again, it was a case of the arbiter being an actor: the sitting Governor was Rick Scott who, having served the maximum two terms, had become the Republican candidate for the Senate.

While giving Trump something to tweet about, the setbacks in Florida and Georgia did not detract ultimately from the bigger reality of the Democrats winning a majority in the House and breaking the Republican monopoly of power.

SUCCESS FOR PROGRESSIVE DEMOCRATS

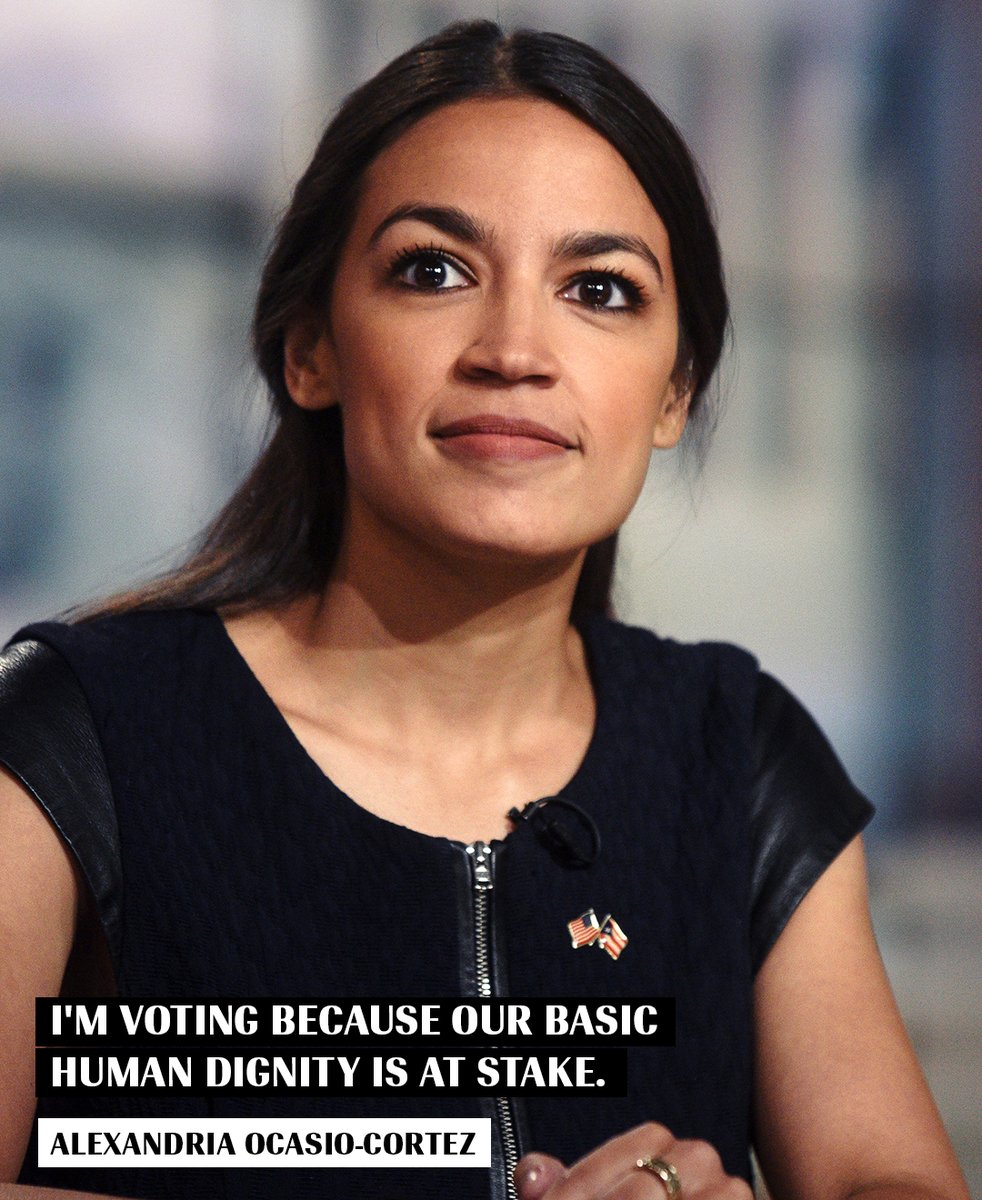

Had Abrams won in Georgia, she would have been the first woman African-American Governor in US history, but there was no shortage of other makers of history. For the first time, Congress will have Muslim women members, Rashida Tlaib (Michigan D13) and Ilhan Omar (Minnesota D5), and Native American women members, Sharice Davids (Kansas D3) and Deb Haaland (New Mexico D1). Meanwhile, at 29, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (New York D14) made history as the youngest woman ever elected to Congress.

Tlaib and Ocasio-Cortez are both members of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and won primaries for selection as Congressional candidates for the Democrats on that basis. They typify the new generation of activists spawned by the 2016 presidential campaign mounted by Sanders, who also identifies himself as a democratic socialist, though not as a DSA member. In the last two years, DSA membership has grown from 5,000 to more than 50,000 and its activists have been elected to state legislatures as well as now to Congress.

The DSA was formed in 1982 and can trace its roots back to the foundation of the Socialist Party in 1901 (see history), but several entirely new groups have emerged from the Sanders campaign, of which the two major ones are:

Our Revolution – This is the political organisation most closely associated with Sanders himself. Under the strapline ‘Campaigns end, Revolutions endure’, it aims to channel the energy that built up around Sanders into support for a new generation of progressive leaders and campaigns around Medicare For All, the Green New Deal, Free College Tuition and other progressive demands. Its mission is to “transform American politics to make our political and economic systems once again responsive to the needs of working families”. In the midterm elections, candidates it backed included Abrams, Gillum, Ocasio-Cortez and Tlaib as well as Pramila Jayapel (Washington D7) and Tulsi Gabbard (Hawaii D2).

Justice Democrats – Formed a few months after Our Revolution, it takes a similar approach but with an emphasis on supporting “fresh non-politicians” and a strong focus on raising money from small donors. “It's time for a Democratic Party that represents its voters, not just corporate donors,” they say. Its midterm election endorsements overlapped considerably with Our Revolution, but it also supported Ayanna Pressley, who – like Ocasio-Cortez – defeated an incumbent corporate Democrat in the primaries to then go on to be the first black woman to be elected to represent Massachusetts in Congress.

The election of candidates supported by these three groups has helped strengthen the Congressional Progressive Caucus, whose membership is expected to increase from 78 to 98. While the caucus includes some members who supported Hillary Clinton rather than Sanders, the new intake from the midterms has favoured the left.

GREEN NEW DEAL

This was reflected in support for a Congressional committee on a Green New Deal, following a protest at the office of incoming House leader Nancy Pelosi by the climate justice group, Sunrise Movement, just after the elections. Within a few weeks, Ocasio-Cortez had gathered support for the formation of a committee from nearly 50 members of Congress, including potential presidential candidate Gabbard, anti-war stalwart Barbara Lee (CA D13) and civil rights veteran John Lewis (GA D5).

Ocasio-Cortez wanted a committee with wide-ranging powers that would be tasked with producing a detailed ‘national, industrial, economic mobilization plan’ to make the U.S. economy carbon neutral. It would be required to report by the start of 2020 and then produce draft legislation within 90 days. Her proposal set the specific target of meeting 100% of national power demand through renewable sources within 10 years. Backing Ocasio-Cortez, Sanders tweeted: “We must look at climate change as if it were a devastating military attack against the United States and the entire planet. And we must respond accordingly.”

Pelosi, however, diluted the Ocasio-Cortez plan by not giving the committee power to initiate legislation or subpoena witnesses and rejecting her proposal to bar Congress members who accept money from the fossil fuel industry. The Green New Deal is far from dead, but Pelosi has demonstrated how reluctant the Democrat leadership is to challenge corporate interests.

THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

At the same time, the Democrat leadership is intent on positioning itself as more bellicose than Trump when it comes to foreign policy – both in attacking his plan to withdraw ground troops from Syria and Afghanistan and in obsessively claiming that an alleged Russian attempt to influence the 2016 presidential election was, as Clinton has put it, equivalent to the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

The pattern is therefore set for 2019. On the one hand, the left is looking to build a movement to challenge Trump on a radical domestic agenda spanning issues such as climate change, healthcare, tuition fees and a $15 minimum wage and on foreign policy in a way that encourages disengagement from regime-change wars while opposing his anti-Palestine, anti-Iran agenda. The Democrat leadership, on the other hand, will seek to curry favour with big business – especially the health insurance and fossil fuel industries – while pinning their hopes on a knock-out blow against Trump from the Mueller investigation into alleged Russian interference in the 2016 US election.

On the latter, no one has much idea what is likely to emerge because it has been so leak free. Last September, Watergate veteran journalist Bob Woodward, when asked if he had found any evidence of collusion with Russia while writing Fear, a book on Trump, said: “I did not, and of course, I looked for it, looked for it hard.”

Woodward did not rule out Mueller having “a secret witness or somebody who has changed their testimony” but, so far, the corporate Democrats are relying on residual Cold War antipathy towards Russia to stir the issue up in a way that’s alarmingly reminiscent of the McCarthy era. Their targets are not only Trump but also anyone on the left who can be labelled as ‘an agent of Russian influence’ because they question a foreign policy that escalates tensions.

With Democrats now jockeying for position to be chosen as the candidate stand against Trump in 2020, the danger is things could turn nasty and they could fritter away the political advantage they’ve gained from the midterm elections. The left needs to stay focused on the issues that matter most to working people.

Steve Howell is author of Game Changer: Eight Weeks That Transformed British Politics, published by Accent Press and available on Amazon, Hive, BooksEtc and his own website: www.steve-howell.com

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISTS OF AMERICA

Both Sanders and the DSA take their inspiration from Eugene Debs, the key figure in the formation of the Socialist Party in 1901, who was imprisoned for supporting resistance to the World War 1 draft. In its heyday, the Socialist Party had more than 100,000 members and Debs could win nearly a million votes as a presidential candidate.

By the 1970s, however, the Socialist Party had become a tiny sect and was taken over by proto-neoconservatives who opposed unconditional withdrawal from Vietnam and changed the organisation’s name to Social Democrats, USA. This in turn prompted their most prominent figure, Michael Harrington, author of The Other America, to leave and form the Democratic Socialist Organising Committee (DSOC).

In another part of the fragmented US left, meanwhile, the New American Movement (NAM) was being founded by New Left activists from Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the socialist-feminist movement. As NAM and DSOC developed during the 1970s, discussions on a merger ran up against the initial reluctance of NAM members to embrace the explicit ‘left-wing anti-communism’ of Harrington’s group.

By 1982, however, they had come together to form DSA, which their own historian, Joseph M. Schwartz, describes as an American socialist movement “committed to democracy as an end in itself” and to work as “an open, independent socialist organization in anti-corporate, racial justice and feminist coalitions with non-socialist progressives.” The fortunes of the DSA ebbed and flowed over the following three decades – with the collapse of communism proving “less of an immediate boon to democratic socialists than many had hoped” and its membership never moving out of the 5,000 to 10,000 range.

It was not until the DSA decided to make its number one priority the movement to support Bernie Sanders in his run for president that its fortunes took a marked upward turn. The Sanders campaign rallied thousands of younger activists - many of whom had cut their teeth in the Occupy Wall Street and other post-2008 crash protest movements – and took the word ‘socialism’ into mainstream politics. That more than 13m voted in primaries for a candidate who self-identified as a socialist was unprecedented.

While for many Sanders supporters the idea of socialism is limited to immediate demands for universal healthcare and free education, the DSA acted as a magnet for those looking for an alternative to capitalism in a more general sense. Schwartz says:

“DSA made clear that Bernie’s New Deal or social democratic program did not fulfil the socialist aim of establishing worker and social ownership of the economy. But in the context of 40 years of oligarchic rule, Sanders’ program proved sufficiently radical and inspiring.”

DSA’s membership is now much like Momentum’s in age and political profile, with similar strengths and weaknesses. Younger activists are outstanding at building mass campaigns but their lack of political knowledge can sometimes be exposed (as happened with Ocasio-Cortez who, when faced with a backlash against her criticisms of Israel, said: “I am not the expert on geo-politics on this issue”). Older activists, on the other hand, may have much greater political knowledge but some of them find it difficult to move on from the sectarian arguments of the past.

Stacey Abrams supporters

Jesse Jackson at polling station