The Spanish civil war 80 years on

By Frieda Park

The Spanish Civil War remains hugely significant despite the 80 years that have elapsed since its outbreak in 1936. The fight to defend the democratic, Republican Government against a fascist military up-rising, the heroic resistance of the Spanish people and the assistance brought to them by the International Brigades still inspires people today.

It was seen clearly at the time by socialists, communists and progressives as vital to stopping fascist advance in Europe, a judgement which proved correct when the fascist victory in the Civil War and "non-intervention" by Western democracies emboldened Hitler's aggression in Europe.

The Republic was defeated by General Franco's fascist forces on 28th March 1939 when they took Madrid and on the 1st of September Hitler invaded Poland, signalling the start of the Second World War.

Strikingly in an age dominated by neo-liberalism and its individualism and selfishness, the Spanish Republic and the Civil War show that a different set of values can prevail. Society can be made better by collective effort and that within us all there is the possibility of courage and self-sacrifice for the common good. It was also an outstanding example of internationalism in action. The Civil War, therefore remains important as a political example when hope sometimes seems to be in short supply.

It has had other ramifications as well, giving rise to debates which rage on today, particularly round the differences on the left within the Republican forces.

In Spain itself there are far greater concerns about how the Civil War and ensuing dictatorship has scarred society and politics. The pact of oblivion (or forgetting) and the historic compromise closed down discussion of the war. It was argued that the best way to ensure a transition to democracy was not to talk about the Civil War or what happened under Franco. There was no national debate, far less any reckoning or justice. Consequently, no-one was held to account for fascist crimes and fascists remained powerful in the establishment. Even to this day republicans can be wary of speaking out and the right resists efforts to expunge symbols of fascism. For years there was no acknowledgement of the suffering of republicans and the crimes of Franco. In Spain the Civil War is not history but is still a live part of people's personal experiences.

These are some of the reasons that interest in the Spanish Civil War remains high.

The Republic and the Civil War

The background to the Civil War was rooted both in the specific economic, political and social conditions of Spain and in the wider context of Europe in the first part of the 20th century.

The victory of the working-class in the Russian Revolution of 1917 sent shock-waves through the capitalist class across the continent. It was determined that ordinary people should not succeed again in over-throwing its system of exploitation and oppression. Throughout Europe working-class movements were viciously suppressed, with leaders such as Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Gramsci executed or imprisoned.

In addition capitalism was falling deeper into crisis. The rivalries that had led to the 1st world war were unresolved. As the working class continued to battle against attacks from capital, so capitalism resorted to fascism to impose its will. In Germany and Italy, Hitler and Mussolini came to power and ruling circles everywhere hoped that fascist aggression would be turned against the Soviet Union.

Therefore, the advent of the Second Republic in 1931 signalled a challenge to reaction both in Spain itself and more widely in Europe. Initially the government introduced reforms including improving the conditions of those working on the land, more autonomy for Catalonia and curbs on the power of the church and the army. All of this incensed the right and a campaign of destabilisation, non-compliance with laws and reprisals against militant workers and peasants ensued. This included an attempted coup in 1932 led by General Jose Sanjurjo. The Spanish Civil War did not, then, come out of the blue, the willingness of the right to use anti-democratic means and military force was evident right from the inception of the 2nd Republic.

This destabilisation and the decision of the Socialist Party (PSOE) to stand on its own, rather than in alliance with other parties led to the defeat of the left in elections of 1933. There then followed bitter repression of workers and peasants, with worsening conditions for ordinary Spaniards. In 1933 a general strike, which became an armed up-rising in Asturias, was brutally put down by troops commanded by General Francisco Franco.

This experience led the left to realise that unity to defeat the right was essential and in January 1936 the Popular Front was formed. It was an alliance of left republican groups, socialists and communists and in elections the following month it won power. (The anarchists, who were particularly strong in Catalonia, did not participate in the Popular Front.)

The breadth of the political forces supporting the republic ranged from liberal capitalists, through socialists, communists, anarchists and trotskyists. Apart from some pockets of industry, such as in Catalonia, much of Spain had failed to develop economically and was dominated by land-owning aristocrats. The Catholic Church was allied with these forces and was particularly reactionary. Although workers and peasants endured the greatest hardships, others such as small business people, and middle-class professionals were frustrated by this state of affairs so it was not only the working-class and the peasants who wished to see change.

The fight for the republic involved all these forces and was not, therefore, a simple fight between left and right, socialism and capitalism or revolution and reaction as it is sometimes misrepresented. It was a fight for democracy against fascism, but within that each political trend and class had its own objectives. When the war broke out uniting these to defend the republic became a central task.

Destabilisation re-started following the left's victory, with right-wing violence, including the killing of some military officers loyal to the government. Other officers who might have supported the new government had already been purged under the previous reactionary administration. The plot to overthrow the Republic was in train as soon as the Popular Front government took office and only five months later the army revolt began.

A central figure was General Franco who had honed his skills in oppression and practiced his brutality in the Spanish colonial army in North Africa. That army was crucial to the up-rising and got to Spain in transport provided by Hitler and Mussolini. Despite the previous coup attempt, key figures in the Government did not take the threat from the military sufficiently seriously and it was unprepared for the rebellion.

However, Franco and the right also underestimated the resistance of the Republican Government and the people of Spain. They believed that they would have a swift victory as the bulk of the Army and the Civil Guard, supported them. They had also prepared for and planned this coup better than the previous attempt. That the easy victory did not happen was due to the determined resistance of the Spanish people. The ensuing Civil War lasted nearly three years.

On one side there was the Spanish ruling class, the aristocracy, the Army and the Catholic Church and on the other the legitimate government of Spain and the people who elected it. It was already an uneven military contest, made much worse by the support given to the rebels by the fascist governments of Italy and Germany, which sent arms, including tanks and aircraft, and troops. It has been estimated that around 108,000 trained regular soldiers from Germany, Italy and Portugal fought for the rebels.[1]

The odds, stacked against the Republican Government and exacerbated by external fascist support were further worsened by the policy of "non-intervention". This was the refusal of western democracies to sell arms to the Republic. Even although fascist countries were openly supporting the rebels, countries such as France and Britain maintained the fiction that the war was a purely Spanish affair. In reality, of course, they knew the score but at that time were more positive about fascism. They were happy to see the Spanish workers crushed and any threat of socialism expunged there. They were even more happy to support fascist aggression, believing that it would be turned against the Soviet Union, the first workers state.

For its part, the Soviet Union did respond to the needs of the Spanish people, although they did not send troops in any numbers as that could have provoked an even more fierce and united reaction against both it and the Republic. Only around 2000 Soviet military personnel served in Spain, however, it supplied 800 aircraft, 360 tanks, 1555 military pieces half a million rifles along with ammunition and equipment and food.[2] Supply lines were the subject of constant attack by rebel forces reducing the aid that got through.

Further support came in the shape of the International Brigades 35,000 men and women from 50 countries who volunteered to defend democracy from fascism: 2,500 of them came from Britain and Ireland.[3] The Brigades were organised under the auspices of the Comintern, the international organisation of Communist Parties, with communists playing a leading role in recruiting volunteers, supporting the republic and fighting on the front line.

The contribution of the Brigades has acquired great symbolism in terms of internationalism and heroism, however, their military contribution was not tokenistic, it was vitally important to the defence of the Republic. Some Brigaders were veterans of previous wars and brought much needed military expertise to the Republican forces, helping train the inexperienced militias. They were also in the front line and played a decisive role in key battles, often at a heavy cost. Of the 500 members of the British Battalion involved in the Battle of Jarama in February 1937, 136 were killed and approximately the same number injured.[4]

The Republic

What the Republic was about is often lost, with the focus on the war. The coming of the Republic signalled a widespread desire for change in Spain. It was a country being held back by the stranglehold of reactionary institutions and the power of the aristocracy. Workers and peasants suffered harsh conditions and the Catholic Church and reaction stifled social and intellectual life. The Republic sought to overturn this order and in doing so challenged the power of the forces which propped it up.

In its new constitution Spain was defined as: "a democratic Republic of workers of all types, structured around freedom and justice. All its authority comes from the people." [5]

It separated church from state and ended state funding for the clergy, also introducing civil marriage and divorce. It banned those in holy orders from teaching.

It gave women the right to vote.

The spirit and principles of the new democratic constitution were developed further in policies enacted by the Government between 1931 and 1933. Measures included:

- Attempts to restructure and reform the Army, one of the bastions of reaction.

- Secularisation of education, with religious symbols being removed from schools and a plan to ban the church from running schools. (In the end there was not enough time to implement this before the election of the right in 1933.)

- A major programme of school building was undertaken with10,000 new schools completed in order to address the problem of the 1 million children who were not receiving an education,

- Setting up the Misiones Pedagogicas to tackle illiteracy, running at 50% of over 10 year olds. It was particularly bad amongst women.

- Making culture available to all, especially to rural areas and cinema and theatre performances were promoted. Federico Garcia Lorca's touring company La Barraca was an example of this.

- Catalonia was granted autonomy and the process of granting similar status to other parts of Spain was started.

- Reform of Labour laws and contracts and conditions became subject to agreement of joint committees of workers and bosses. The right to strike was guaranteed.

- Landowners were prevented from bringing in outside labour, while local labourers were unemployed.

- Steps were taken to reform agriculture. Workers were given the right to take over abandoned estates and compulsory purchase of aristocratic estates and neglected land was introduced.[6]

Despite the right-wing government rolling-back these gains, the election of the Popular Front in 1936, which was pledged to resume the process of reform, raised expectations. However, the military rebellion against the government meant that these hopes could not be properly fulfilled. Nevertheless, throughout the conflict the Government continued to do as much as it could to implement progressive polices in education, culture, land reform, workers' rights and the emancipation of women. Schools continued to be built, literacy programmes implemented, children's camps, education centres for workers and cultural militias were established.

Even when war broke out, social advances were still a priority. In 1937 the education budget was bigger than the that for the military. Steps were taken to protect the nation's cultural heritage from destruction during the war and art works were evacuated from the Prado in Madrid. Private ownership of art was labelled a "social crime".

The left and the ultra-left

Whilst the war was one of democracy versus fascism, political developments in Spain meant that this was not only about who won elections, but also about a deeper democracy involving people more directly in creating a society that would meet their needs.

With the dire threat posed to the Republic by the fascist military up-rising, there was a divide within the Republic about the direction of social change. The ultra-left believed that pursuing revolution was the best guarantee of the survival of the Republic. For communists and socialists, however, the priority was the defeat of fascism, without which there could be no further social transformation. Whilst there were areas where popular control was being implemented, they argued that the conditions did not exist for revolution throughout Spain and that pursuing such a line would lead both to failure and be a dangerous diversion, undermining the anti-fascist fight. This debate rages on today and is the fault-line which divides a socialist or communist analysis of the civil war from a trotskyite and to a lesser extent anarchist analysis.

A main advocate of the revolution first line was the Partido Obrero de Unificacion Marxista (POUM) which was a small quasi-trotskyite split from the Spanish Communist Party (PCE). This led it into conflict with the Republican Government and the Communist Party as it diverted efforts from the central fight to defend the republic into supporting its own objectives. This reached a low point in May 1937 when the POUM and the anarchists fought against the Republican Government in Barcelona.

Anarchism had a longer tradition in Spain and strong support in parts of the country. It was a significant force in the defence of the Republic and, after the war broke out, anarchists joined the Government in November 1936 holding four ministerial posts.

However, they too often pursued counter-productive policies such as forced collectivisation. They were sometimes responsible for meting out indiscriminate violence which did not serve any real military purpose. They found it hard to accept the discipline and centralisation of the war effort which, combined with their desire to concentrate on developing anarchist models in areas they controlled, meant their forces were not always effectively deployed in the defence of the Republic. Ultimately the Anarchists joined the coup within the Republic during its last days instigated by those who wished to sue for peace with Franco.

Some well-known representations of the Civil War, like George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia and Land and Freedom by Ken Loach support the ultra-left narrative. The critiques of these views by International Brigaders receive little publicity, while Orwell and Loach remain feted.[7] Loach has his central character rip up his Communist Party card, yet the reality was that as the war went on support for the PCE grew spectacularly. In 1922 it had only 5,000 members, which by the start of the Civil War had increased to 30,000. In the next five months this swelled to 100,000 and by the time the Party was legalised in 1977 it had over 200,000 members.

This was not a Party that had sold out the Republic or the people of Spain, but one which had won their huge respect, not only during the war but in the resistance to the dictatorship after the war ended. This was due to the correctness of its political line which made unity to defeat fascism and the war effort the priority for the Republic. It also argued for the centralisation of that effort to combat the powerful, well-armed and professional fascist military forces. Communists showed themselves to be brave and well-organised and without the contribution of the PCE, communists world-wide and the Soviet Union, the Republic would not have survived as long as it did.

The Defeat of the Republic

Despite the heroic struggle of the Spanish people the fascists continued to gain ground. Desperate to try to change the attitude of western democracies the Government decided to withdraw the International Brigades. Their final parade was in Barcelona on 29th October 1938, where they were movingly addressed by Delores Ibarruri (La Pasionaria). Final appeals for help were ignored and the Republic faced defeat.

Throughout the entire duration of the war Madrid held out. Of course, Franco pushed to take the capital early on, but was rebuffed by the resistance of the Madrilenos, the militias and the International Brigades, including the British Battalion, which played such an important role at Jarama. A grotesque triumphal arch, built after the war, still stands at the furthest point Franco reached on the edge of the city until it finally fell on 28th March 1939.

Wherever he advanced Franco maximised the level of destruction and his troops committed atrocities on Republican soldiers and civilians alike. The bombing of the Basque town of Guernica was one example of this deliberate targeting of civilians aimed at destroying physically and psychologically the Republican people of Spain. Such acts were precursors to the continued savage repression of Republicans in the ensuing decades.

A better understanding of the nature of state power might have helped the Republican government realise the threat from the military and pre-empt it. Disunity on the left and misguided, diversionary attempts to foment revolution did not help either, however, the main reason for the Republics defeat was that it was up against a professional, well equipped and disciplined army, whilst its forces were comprised of volunteers; ordinary citizens, untrained and ill-equipped who had no military experience. Furthermore, the obscene policy of non-intervention prevented it getting help and arms that it needed to survive. Non-intervention, however, did not prevent other fascist powers sending troops and arms to assist Franco.

Ultimately it was the ruling classes of Europe and Spain that defeated the Republic by effectively supporting the anti-democratic fascist coup. In doing this they emboldened other fascist powers in Europe and paved the way for the Second World War.

[1] Preston, Paul the Spanish Civil War Harper Perennial 2006 p 172

[2] Alexander, Bill - British Volunteers for Liberty, Lawrence and Wishart 1986 p 23

[3] Baxell, Richard, Jackson, Angela, Jump, Jim Antifascistas, Lawrence and Wishart 2010 p 11

[4] Ibid p 46

[5] Quoted in: Casanova, Julian, The Spanish Republic and Civil War, Cambridge University Press 2010 p 32

[6] Ibid pp 40-47

[7] Alexander, Bill George Orwell and Spain 1984 re-printed from Norris, Christopher ed, Inside the Myth, Lawrence and Wishart 1984 & Graham, Frank Slanders about the International Brigade in The Spanish Civil War: Battles of Brunete and the Aragon. 1999

1940: SS Commander and leading Nazi, Heinrich Himmler (centre left) next to Fransisco Franco in Madrid.

Soldiers of the 11th International Brigade at the Battle of Belchite on board a Soviet T-26 tank.

Poster from the Spanish trade union UGT showing a caricature of a foreign supported Franco followed by a general, capitalist and priest.

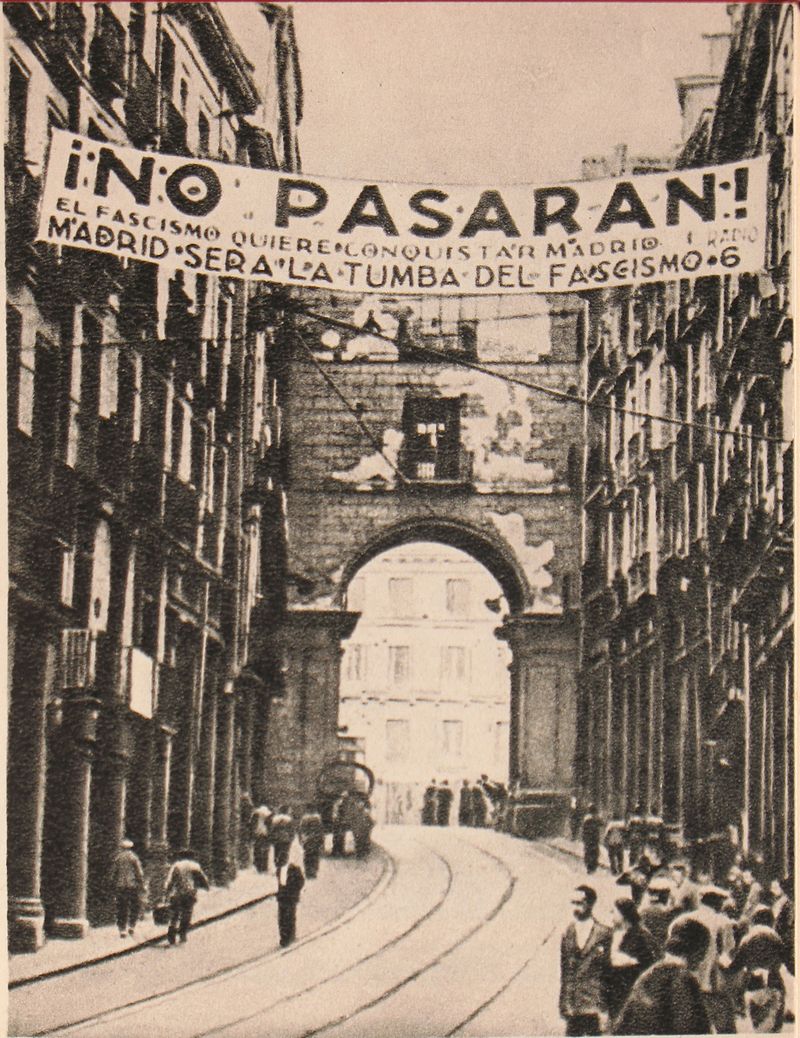

1936-39: A Republican anti-fascist banner in Madrid which reads, 'Madrid shall be fascism's grave'.

1936 Delores Ibarruri - 'La Pasionaria'