The few versus the many

By Clare Bailey

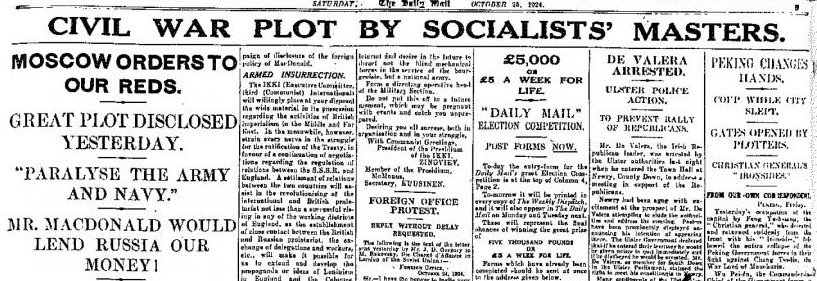

It is not unknown for Labour leaders and policies to come under sustained attack in the British press during an election campaign, in fact it’s absolutely normal. From the Zinoviev letter to the fake queue in the 1979 Labour Isn’t Working poster to the Russian Twitterbot smears during the last election, disinformation has long played a significant role in undermining the electorate’s confidence in the Labour Party and its manifestos.

But a post-election 2017 London School of Economics report on press coverage suggested that there was something different going on this time, not only determining as one might expect that “sources that were anti-Corbyn tended to outweigh those that support him and his positions,” but also that he was “systematically treated with scorn and ridicule in both the broadsheet and tabloid press in a way that no other political leader is or has been” (my italics) and that “UK journalism played an attack dog, rather than a watchdog, role.”

SPECTRES

Corbyn’s personal popularity, the massive growth in Labour Party membership since he became leader and a steady focus on developing anti-austerity policies have posed all kinds of problems and raised some spectres for those with vested interests in keeping things as they are – not least for the majority of the Parlimentary Labour Party, which has consistently undermined Corbyn’s authority and sought his removal as leader. The relentless campaign on the issue of anti-semitism has been one hostile response and has been successful to some extent in causing distraction and division - though perhaps less successful than many had clearly hoped. Efforts now seem to be moving in a modified direction with Chuka Umunna’s widely covered statement this week (September 10) that the Labour Party is institutionally racist.

The unusual intensity, tenacity and violence of this campaign need to be kept in mind as we think about what would be likely to happen as Corbyn continues to survive this onslaught and if the next general election, whenever it is called, returns a Labour government determined to turn its manifesto commitments into realities. These attacks would be raised to the power of 10. ‘For the Many, not the Few’ are simple words but they are being taken seriously by more than Labour Party members.

FINANCIAL BACKLASH

Looking past the many obstacles in the way of a left Labour government to a transformed political landscape in which a Corbyn administration is in office, it’s important to recognize what would be at stake and for whom. Journalist Adam Blanden, in an interesting article on Novara Media last year, put it this way: If elected, and if it stumps up the promises outlined in current policy thinking, the current Labour Party would likely be the most politically radical government to ever lead an advanced western economy. It’s worth recalling what has happened to newly elected governments on the left within the last 50 years – the Allende government in Chile and, closer to home, the Syriza government in Greece were not managing ‘advanced western economies’. Measured by GDP the UK economy is the 5th largest in the world. It is dominated by a huge services/banking sector accounting for almost 80% of GDP, sterling plays an important role in global finance, and foreign investment into the UK is massive – almost £200 billion in 2016. A Labour government elected on the current manifesto will be the first for a long time with the declared aim of interfering with the ability of capitalists to make unlimited profits at our expense in this perilously skewed economy.

Global capital is bound to resist the transformation planned by Labour. Most economists seem to agree there will be an immediate backlash in the financial markets and capital flight on a huge scale – the ‘sudden stop’ phenomenon which sees a reversal of capital inflow and leads to a sudden contraction in GDP. On June 13th 2018, John Glen, former Economic Secretary to the Treasury, was reported on the Financial Times website as saying that a ‘maverick’ Labour Party poses a greater risk to the Square Mile’s future than Brexit and calling for financial executives to wake up to the risks posed by having an avowed Marxist as Chancellor. City traders and forecasters have clearly been awake to the risks for some time, however, as this comment in The New European after the Labour Party conference in September 2017 shows: “Anti-business policies are not unique to Labour, but Labour has this week shown that even in the face of a massive threat to the economy like Brexit, it will wage war against the companies that employ people, pay corporation tax, provide income for our pension funds and so much more. It’s easy to dismiss conference speeches as hot air – especially since McDonnell’s was an uncosted speech about actions that would be illegal, without compensation – however the companies under threat cannot be so complacent. They will not go on the record to respond to Labour’s provocations but their leaders now have a responsibility to begin war-gaming a Labour victory.” One fund manager put it more succinctly: ‘If an election were called, we would avoid UK assets with extreme prejudice.’ They think Labour would win.

WAR GAMES

The journalist in The New European reached instinctively for military metaphor but the serving British Army general, who, soon after Corbyn’s election as leader, commented on possible future decisions of a Corbyn government, was not speaking figuratively when he talked about officers using all means at their disposal to prevent the country’s security being compromised. He warned there would be a direct challenge if these decisions, on nuclear weapons for example, unsettled the status quo: ‘The Army just wouldn’t stand for it. The general staff would not allow a prime minister to jeopardise the security of this country and I think people would use whatever means possible, fair or foul to prevent that. You can’t put a maverick in charge of a country’s security. There would be mass resignations at all levels and you would face the very real prospect of an event which would effectively be a mutiny.’ The circumstances in which this threat might be activated were left undefined but this stands as a clear warning that a democratically elected government has only so much room for manoeuvre before democracy would be suspended.

Mass resignations, mutiny – these do not necessarily amount to what we think of as a coup and the general in question did not conjure up the picture of tanks in Whitehall – but a refusal by the armed forces to obey the orders of the government would trigger a crisis intended to bring down the government.

Threats of a military kind have also come from other sources. Would a warning shot (and this one was addressed to the current Conservative government) look anything like this extraordinary letter about NATO commitments? – sent by James Mattis, US Defence Secretary to his counterpart, Gavin Williamson, in June this year and leaked to The Guardian:

“I am concerned that your ability to continue to provide this critical military foundation for diplomatic success is at risk of erosion, while together we face a world awash with change ... A global nation like the UK, with interests and commitments around the world, will require a level of defence spending beyond what we would expect from allies with only regional interests. As global actors, France and the US have concluded that now is the time to significantly increase our investment in defence. Other allies are following suit ... It is in the best interest of both our nations for the UK to remain the US partner of choice. In that spirit, the UK will need to invest and maintain robust military capability. It is not for me to tell you how to prioritise your domestic spending priorities, but I hope the UK will soon be able to share with us a clear, and fully funded, forward defence blueprint that will allow me to plan our own future engagement with you from a position of strength and confidence. In advance of that, the president and I look forward to hearing details of the progress you have made with your Modernising Defence Programme at the upcoming NATO summit.”

No accident that this was sent not only before a NATO summit but also to a government under pressure to save its skin by forming a government of national unity, and to a country that might well soon elect a professed NATO sceptic as its Prime Minister. Under Corbyn’s leadership, foreign policy might well look very different from anything the UK – or the US – has seen before. Corbyn’s under-reported speech to the UN in Geneva in December 2017 is well worth reading.[1]

EUROPEAN UNION

International interference may well come in preemptive form from other quarters; the EU does not especially want a socialist – or even a social democratic – beacon lit off its shores. Earlier this year The Times cited senior Brussels officials who were said to be pushing for a hard-line “level playing field mechanism” in a future trade deal with the UK because they are concerned that Labour’s nationalisation programme and subsidy plans would make it harder for EU companies to compete. EU officials were thought to be drawing up a so-called “non-regression” clause designed to entrench free-market policies in the UK’s exit deal.

THE BLINK OF AN EYE?

There are other parts of the establishment less absolutely opposed to the prospect of a left Labour government at this point, and more differentiated analyses coming out of the City. Under the general heading of ‘Cripes!’, an article posted in May this year on the site poundsterlinglive.com gave a number of different possible outcomes after the election of a Labour government and began by quoting two economists at the consultancy Capital Economics: "Forget Brexit – the biggest thing that could happen to the UK economy in the next year or two is a change of government. In particular, we could soon be looking at a Labour government, with Jeremy Corbyn as Prime Minister.” But they don’t go on to predict disaster – in part because of the role of the Bank of England: "It is easy to promise all manner of things when in opposition. But when it comes actually to hammering out policy, paying for it and getting it passed through government, ambitions can quickly become curtailed," the economists write. "The Bank of England would also act as a constraint.” Interesting in the light of this prediction that so much effort has recently gone into securing maximum continuity in this vital area of control by extending Mark Carney’s run as governor of the BoE to 2020.

Another possibility being considered by the establishment was floated by Michael Heseltine in December last year. In an interview with the Limehouse Podcast he said a Corbyn government would have a negative effect on the country, but leaving the EU would be worse in the longer term. Asked what would happen after five years of a Corbyn government, Heseltine, a lifelong Europhile, said: "We have survived Labour governments before. Their damage tends to be short-term and capable of rectification. Brexit is not short-term and is not easily capable of rectification. There will be those who question whether the short-term pain justifies the avoidance of the long-term disaster." Charles Moore of The Telegraph agreed: “Michael Heseltine has got into trouble for saying that a government led by Jeremy Corbyn would be better than Brexit. I am not sure that one would prevent the other but, from his point of view, he is right. Compared with the great European destiny, a Corbyn administration is but the blink of an eye. One purpose of the European Union is to ensure that it makes little difference who runs the government of a member state: the real power is elsewhere. Remainers like that. Leavers don’t.” And The Financial Times agrees, quoting currency experts at Dutch bank ING earlier this year: “If a credible Labour-led coalition can be formed quickly, then we are likely to see markets price in greater odds of a softer Brexit deal and this could arguably help the pound recover from any initial sell-off. From the currency’s perspective, this channel is likely to outweigh any questions over Labour’s economic policies.” The price of course of any such arrangement is likely to be the manifesto and the ‘credible coalition’ is what has been urged on the Labour party by some of its own MPs under the name of national unity. The alternative to this is the 3rd party option, constantly on the edges of the news headlines and in the wings, but not so far attractive enough to those tempted by it.

INTELLIGENCE

Leaks to the right wing press earlier this year about Corbyn’s alleged links with Communist spies during the cold war period caused a brief flurry, but like most of the accusations, innuendos and slurs there have been over the last 2 or 3 years, they died away. In 2016 Len McCluskey suggested the intelligence services were operating inside the Labour party, an idea that seems at least possible if not likely given what we know about their operations in the past. How these things would develop and what kind of role they would play if the Labour Party formed a government remains to be seen, but one interesting and unintended side-effect of all the media assaults and attempts to divide the LP internally over the last two years is perhaps a wiser and more sceptical electorate generally – and a more robust and ready LP membership, one less easily spooked than some might have hoped, and with useful recent experience dealing with trouble-making of different kinds.

An establishment presently divided over Brexit – united perhaps only in its attempts to prevent the election of a Labour government (although the Heseltine line suggests there may be interesting disagreement here too) – would unite very quickly behind efforts to create an atmosphere of uncertainty and chaos around a Labour government setting about implementing its manifesto commitments, and would do its utmost to make use of any economic problems arising from a badly negotiated exit from the EU. Everything would then depend on popular support – and that in turn depends on the efforts being made now in every Labour Party branch and constituency to involve members and a wider public in discussion and to publicise the anti-austerity policies that have caused such consternation amongst the powers-that-be.

[1] https://labour.org.uk/press/jeremy-corbyn-speech-at-the-united-nations-geneva/

Jeremy Corbyn

Daily Mail October 1924: the Zinoviev letter

The City of London