The case of Julian Assange

by Clare Bailey

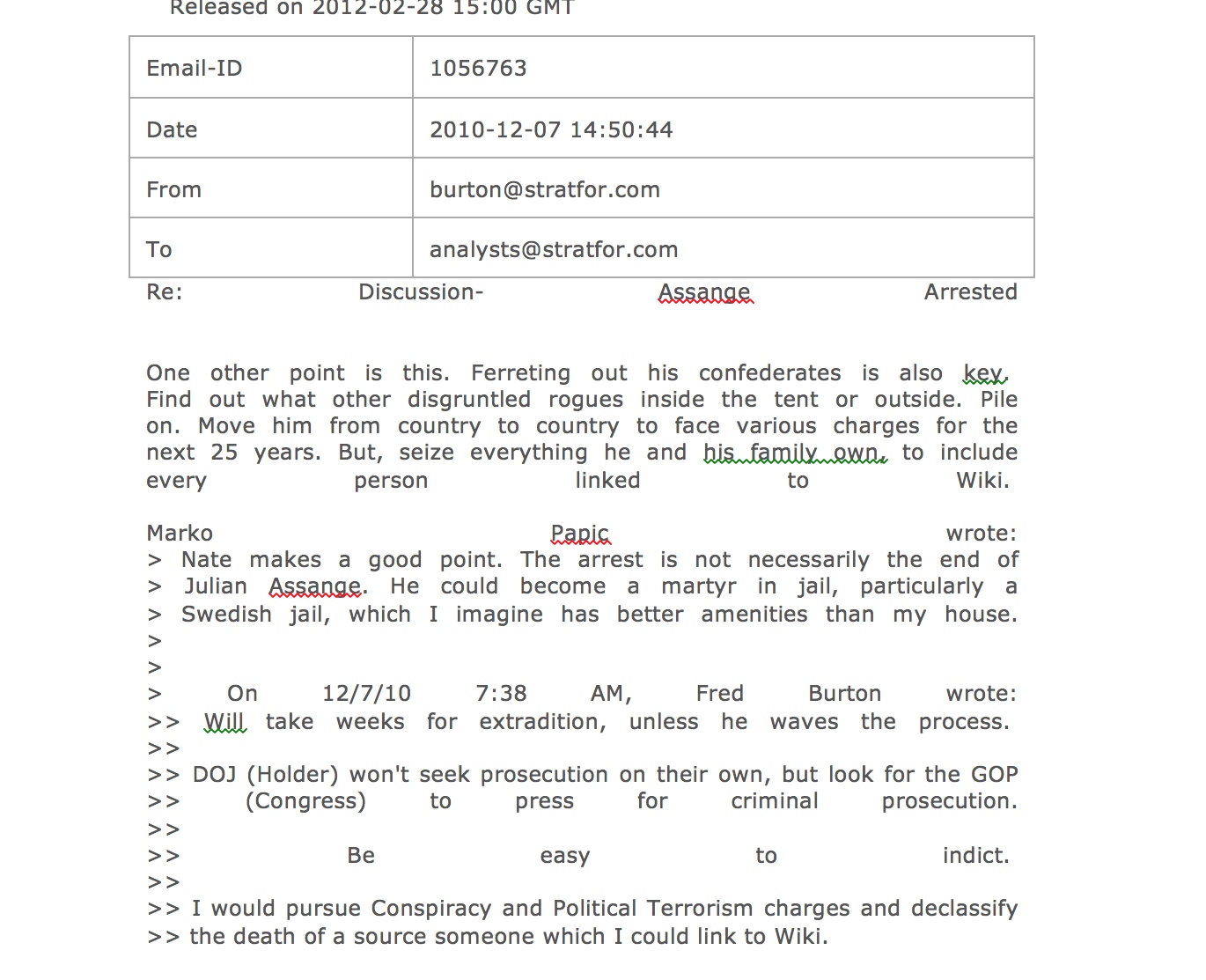

If you have never visited the WikiLeaks site, now – as we approach the final stage of the Assange extradition hearing – would be a good time to do that. You could do worse than begin by dipping into its Global Intelligence Files – 5 million emails from Stratfor, a ‘geopolitical intelligence platform’ based in Texas. Stratfor provides services to huge corporations like Raytheon and Lockheed Martin as well as to government agencies like the US Department of Homeland Security. The emails are directly revealing of Stratfor’s networks and methods – the following one for example, in which Fred Burton, their chief security officer, discusses the arrest of Julian Assange in the UK in December 2010 and advocates moving Assange ‘from country to country to face various charges for the next 25 years.’

In the event, the US used the 1917 Espionage Act rather than conspiracy or political terrorism charges, and did not need to move Assange from country to country. The Swedish government’s 2010 warrant for his arrest on concocted allegations of rape and molestation was sufficient to keep him in suspension in the UK, on bail until May 2012 when the UK Supreme Court ruled he should be extradited to Sweden and fearing subsequent extradition from there to the US, he took refuge in the Ecuadorean embassy where he remained for the next 7 years.

Anyone with questions about the rape allegations made against him should read Republik’s: A Murderous System, an interview with Nils Melzer, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Torture, published on January 31st 2020. Melzer’s account of the Swedish authorities’ actions and proceedings against Assange is uniquely well-informed and makes it clear how the fictitious charges came about and were rapidly instrumentalised by the countries involved: https://www.republik.ch/2020/01/31/nils-melzer-about-wikileaks-founder-julian-assange . All the charges were eventually dropped.

The US has been more than willing to play a long game. Assange has now been persecuted – tortured according to Melzer’s official report – for a decade. His long incarceration in the Ecuadorean embassy provided the Americans with the opportunity to destroy his reputation and discredit him personally, so that he was cut off from public support. He was turned into a living example of the punishment any journalist would suffer if they dared receive and publish material from whistleblowers like Chelsea Manning. In the same interview with Republik, Melzer states: ‘In 20 years of work with victims of war, violence and political persecution I have never seen a group of democratic states ganging up to deliberately isolate, demonize and abuse a single individual for such a long time and with so little regard for human dignity and the rule of law.’ The ‘democratic states’ he refers to are the US, the UK, Australia, Sweden and, latterly, Ecuador.

Manning herself was arrested in 2010, convicted under the Espionage Act in 2013 and sentenced to 35 years. She served 7 years of that sentence before being pardoned by Obama as he left office. She was re-arrested and convicted in 2019 for refusing to testify against Julian Assange to a grand jury investigating the Assange case in preparation for the extradition hearing now in progress in the UK. She was released a second time in March 2020 after a suicide attempt; her release was accompanied by the statement that her imprisonment ‘no longer serves any coercive purpose’.

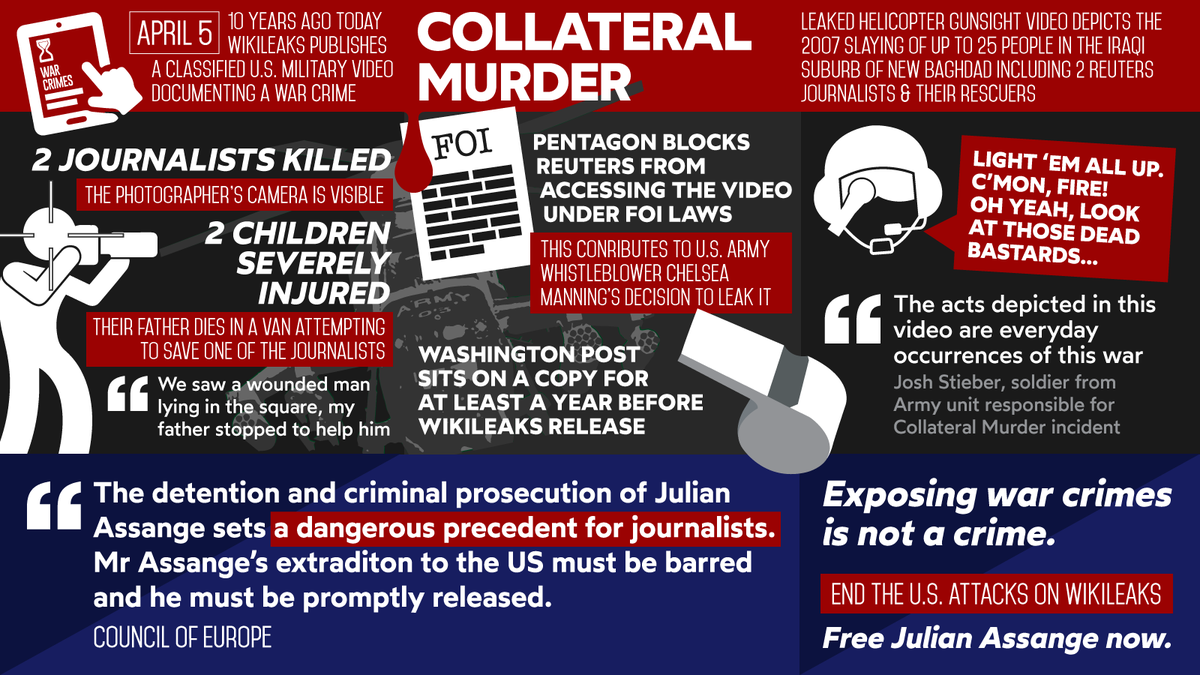

WIKILEAKS

Assange founded WikiLeaks in 2006. A publishing platform for whistleblowers, it describes itself as ‘an uncensorable system for untraceable mass document leaking’. Ten years after its first publications, in his first speech as director of the CIA in 2017, now US Secretary of State Pompeo defined WikiLeaks as ‘a hostile intelligence service’. It was in 2010 that it came to most people’s attention when it leaked the first of the files lodged with it by Manning. These were, in April of that year, the Collateral Murder footage of the 2007 US airstrike on unarmed civilians in Baghdad and, in July, the Afghan War Diary, internal US military logs of the war in Afghanistan. Worth noting again that the first rape charges against Assange were brought by the Swedish government in August 2010.

Collateral Murder (so-named as corrective to the repulsive euphemism ‘collateral damage’) is described by WikiLeaks as ‘a classified US military video depicting the indiscriminate slaying of over a dozen people in the Iraqi suburb of New Baghdad - including two Reuters news staff.’ Released on April 5th 2010, the full version is 38 minutes long and the footage, compared with other officially released film, is unusually clear. It suggests that the public is misled by the brief clips broadcast occasionally on news channels into believing that there these gunships can’t see the ground very clearly. In Collateral Murder the grotesquely named Apache helicopter circles the same patch of residential neighbourhood endlessly; the soldiers inside can be heard deliberately and consciously discussing what they’re doing. They shoot indiscriminately at a group of men, one of whom may have been armed – it’s hard to tell; two of the ‘objects’ however turned out to be cameras carried by Reuters journalists. The dialogue continues to shock however many times one hears it: ‘Light ‘em all up.’ The group instantly falls to the ground and the bodies are covered by the dust cloud raised by the storm of bullets. Then the crosshairs settle on a wounded man trying to crawl to shelter. They open fire on a van that comes to try and pick up the wounded and kill another ‘4 or 5’. ‘Look at those dead bastards. Nice.’ Then they see a child in the van: ‘Looks like a kid.’

Kristinn Hrafnsson, editor-in-chief of WikiLeaks since Assange stood down in 2018, said that when he first saw the film with Assange it was the word ‘Nice’ that bore the full weight of the horror he was watching, ‘the callousness of the imperial mind’ in action as a recent WikiLeaks podcast put it. Hrafnsson went to Iraq 3 years later to try to find the children who’d been in the minivan and was successful. He learned their father had been taking them to school and was killed protecting them from bullets; they themselves had been wounded in the attack and bore the scars.

The reaction of the US military to the film was that it was a “partial picture” and that everything that took place was anyway within the rules of engagement. Lawyers acting for the US Army advised that since no one can surrender to an aircraft, the people killed were killed legally. Later on when WikiLeaks published the Iraqi War Logs, it became clear that this was no isolated event and that the assassination and the killing of civilians was normal. There have been over 200,000 documented civilian deaths since the beginning of the war; the only thing that distinguished the killing filmed in Collateral Murder from 1000s of others was that the unedited film was successfully released into the public realm.

The Afghan War Logs were released a few months later. Published in The Guardian, Der Spiegel and The New York Times, it was one the largest leaks in the history of the US military. As stated in the overview provided by WikiLeaks: ‘The material shows that cover-ups start on the ground. When reporting their own activities, whether directly or via embedded journalists, US Units are inclined to classify civilian kills as insurgent kills, downplay the number of people killed or otherwise make excuses for themselves.’ Taken together the archives show, again in the words of WikiLeaks, ‘The vast range of small tragedies that are almost never reported by the press but which account for the overwhelming majority of deaths and injuries.’

In the age of the embedded journalist, Manning and WikiLeaks enabled the public to see what routinely happens when imperialist armies are deployed in adventurist wars.

A WORD ON 'EMBEDS'

The ‘embed’, defined as a journalist attached to a specific military unit for a period of weeks or months, was the creation of the US military determined to control reporting of major conflict. After journalists reported critically on operations during the war in Vietnam, especially after the Tet offensive in 1968, media-military relations were no longer considered ‘safe’. As the press increasingly questioned strategy and reported significant defeats, public opinion began to change and to challenge decisions to send ever more troops. Some decades later, in February 2003 an unclassified US government report included the following Pentagon statement: ‘Media coverage of any future operation will, to a large extent, shape public perception of the national security environment now and in the years ahead. This holds true for the US public, the public in allied countries whose opinion can affect the durability of our coalition, and publics in countries where we conduct operations, whose perceptions of us can affect the cost and duration of our involvement.’

The Iraq war began six weeks later.

Embedded journalists have said that they become attached to the soldiers in the units they work with. There are strong emotional incentives to omit the worst of what they see and hear, as well as political ones; the reports they send back to their editors present an entirely sanitised version of the truth on the ground. In an essay written in 2008 for The Stanford Journal of International Relations, Kylie Tuosto writes: ‘What embedded reporting shows …. is the media and military are now accomplices in the creation of a Hollywood-esque dramatization of war in Iraq used to propagate pro-war sentiment at home as well as justify America’s presence in overseas conflict’ (The Grunt-Truth of Embedded Journalism, 2008)

INSIDE THE EMBASSY

Assange’s 7 year stay in the Ecuadorean embassy was officially neither detention nor imprisonment, but while the threat of extradition hung over him it was impossible for him to leave. A sympathetic Ecuadorean government granted him citizenship in December 2017 and while left-wing President Correa was in office, he was safe from arrest. This relative security did not, however, prevent the destruction of Assange’s reputation in the British press. By a process of consistent insinuation, rumour and smear, he was cut off from progressive public support and the reason for his incarceration was obscured behind the trumped up image of a sex offender created by journalists willing to do the state’s work. Most journalists ignored what was happening to Assange, and those who did pay attention obsessed about his personal traits, his hygiene, his cat, and of course the Swedish allegations, which no one took the trouble to investigate properly. The NUJ was notable for its absence from campaigning. When Moreno was elected president of Ecuador in May 2017, things changed dramatically. Moreno discussed Assange with Trump’s advisor Manafort and later with Vice President Mike Pence. Assange’s internet access was cut off and the level of surveillance was stepped up. Spanish security company Undercover Global Ltd was later found to have been supplying audio and visual information about Assange’s meetings with his lawyers directly to the CIA. Assange’s Ecuadorian citizenship was revoked in April 2019 and he was immediately taken from the embassy by force. Since then he has been held on remand in Belmarsh high-security prison – in solitary confinement until earlier this year when Belmarsh prisoners demanded his release into normal detention.

THE EXTRADITION HEARINGS

The first phase of the hearings took place over 4 days in February this year. The judge overseeing the hearings, Lady Arbuthnot, could hardly be a more compromised figure after a report by DeclassifiedUK in November 2019 revealed that her husband ‘has financial links to the British military establishment, including institutions and individuals exposed by WikiLeaks’. Her son also has links to an anti-data leak company, Darktrace, set up by the UK intelligence establishment and staffed by US intelligence officials. She has refused to declare any conflict of interest, and though she has since appointed a junior presiding judge for the Woolwich sessions, Vanessa Baraitser, she remains in charge of the extradition case overall. According to Craig Murray, former British ambassador who attended the hearings: ‘When enquiring about facilities for the public to attend the hearing, an Assange activist was told by a member of court staff that we should realise that Woolwich is a “counter-terrorism court”. That is true de facto, but in truth a counter-terrorism court is an institution unknown to the UK constitution. Indeed, if a single day at Woolwich Crown Court does not convince you the existence of liberal democracy is now a lie, then your mind must be very closed indeed.’

Argument over the first 4 days was focused on the terms of the UK-US extradition treaty and the nature of the charges against Assange. An excellent account of those days in court can be found on Murray’s blog: https://www.craigmurray.org.uk According to him and others who were in court, the treatment of Assange throughout was brutal. The International Bar Association issued a strong condemnation:

‘The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) condemns the reported mistreatment of Julian Assange during his United States extradition trial in February 2020, and urges the government of the United Kingdom to take action to protect him. According to his lawyers, Mr Assange was handcuffed 11 times; stripped naked twice and searched; his case files confiscated after the first day of the hearing; and had his request to sit with his lawyers during the trial, rather than in a dock surrounded by bulletproof glass, denied.’

In his summary at the end of this first stage of the hearings, which are set to continue in May unless Assange’s lawyers succeed in having them postponed until September, Murray wrote that in its proceeding against Assange, the US is claiming universal jurisdiction. It is claiming the right ‘to charge anyone of any nationality, anywhere in the world, who harms US interests...’

HEALTH FEARS

Assange is one of only 2 (out of 797) inmates held in Belmarsh for violating bail conditions. Most are there on charges of, or convictions for, far more serious offences. And Assange has anyway now been held for longer than the 50 weeks he was originally jailed for in April 2019; he is in detention without charge. In November 2019, well before the coronavirus outbreak, 60 doctors sent a letter to the Home Secretary expressing serious concern about the state of Assange’s health: ‘We have real concerns, on the evidence currently available, that Mr Assange could die in prison. The medical situation is thereby urgent. There is no time to lose.’ The number of signatories increased to 117 by 9th April.

On March 25th 2020, Assange’s lawyers applied for his release on the grounds of seriously impaired health. The request was refused by the presiding judge Vanessa Baraitser, who ruled that the Covid-19 pandemic does not provide grounds for his release. She came to this decision despite the fact that at that time there were already outbreaks in prisons. At the time of writing, 9 prisoners (one of them in Belmarsh) and 2 prison staff have died of the virus. In addition 100 Belmarsh staff are currently self-isolating.

4000 prisoners are to be temporarily released from British prisons as a result of the epidemic. Julian Assange will not be one of them.

Leaked e-mail