South African lesson of hope for Palestine

by Christabel Gurney

- Based on her speech to the West London Palestine Solidarity Campaign Conference

Chief Albert Luthuli, who was President of the African National Congress in the late 1950s and 1960s, described apartheid by explaining what it meant to black people in South Africa.

“I would like tell you what apartheid really means to us. It means that our men cannot move from country to town and from one part of town to another without a pass. Now our women too will be unable to leave their houses without a pass. It means that 70 per cent of my people live below the breadline. It means that in my own province of Natal 85 per cent of children are suffering from malnutrition. It means massive unemployment. What apartheid means is a long tale of suffering. In a word, it means the denial of dignity and of ordinary human rights.”

Anyone reading this today would be reminded of conditions on the West Bank and Gaza. Looking more closely, there are close similarities between apartheid South Africa and the situation today in Palestine – and in Israel – but there are also very important differences that have implications for political action.

BRITISH RESPONSIBILITY

In 1910 the Union of South Africa was set up as a federation of four provinces with different histories but with one thing in common – that the Africans formed the majority of the population but they were dominated by whites. As with Israel and Palestine the British had a lot to answer for. At the time of the Union Africans trusted that Britain would not relinquish sovereignty without guarantees of some rights – but they got nothing.

South African whites claimed a historic right to the land, but in South Africa as in Israel in fact they pushed out the local population. Dutch sailor Jan van Riebeeck set up a refreshment station in the Cape in 1652. Later the settlers claimed that the Xhosa people did not migrate south to South Africa until later, but this was not true.

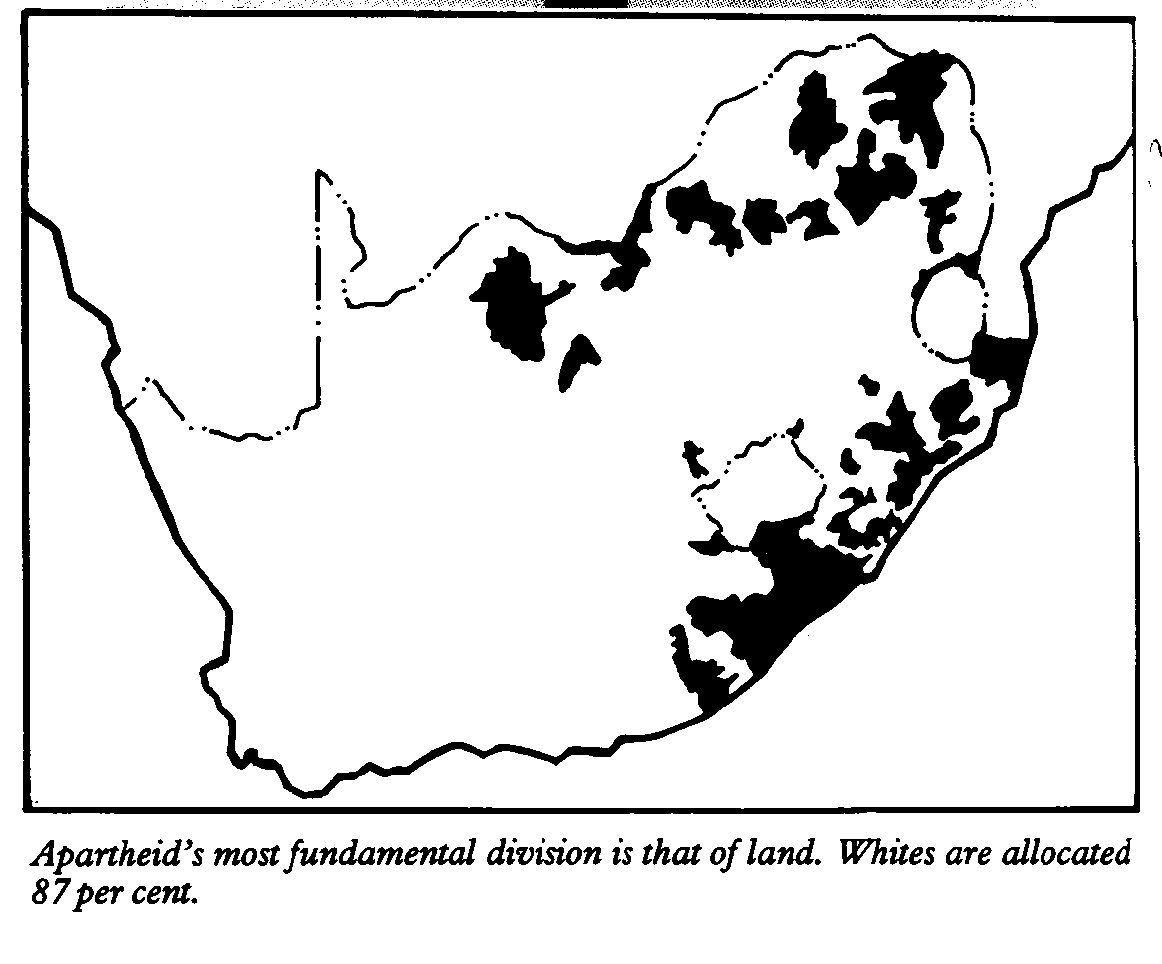

The Act of Union was swiftly followed by the Land Act in 1913 which gave whites, who made up one fifth of population, 87 per cent of the land. Africans who formed the vast majority of the population were allocated 13 per cent. The was land without any of South Africa’s rich mineral resources and it was fragmented and split up. The movement of Africans into so-called white areas was regulated by pass laws. In the early years of union many of the later features of apartheid were present but in ad hoc ways.

To fast forward to 1948, a significant year for both Palestine and South Africa, the National Party unexpectedly won the whites-only election and quickly introduced apartheid. Apartheid schematised and translated what was already common practice into law.

The first step was to introduce rigid population classification: so-called Bantu, Coloured and Indian and so-called European or white. People’s whole lives depended on how they were classified. A powerful short story by the African writer Alfred Hutchison, published in the left-wing magazine Fighting Talk in the 1950s, describes the chaos caused in the life of its protagonist when his classification was changed from Coloured to African.

LAND

The 1959 Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act formalised the land situation and created a new political set-up. The Act deprived Africans of citizenship in South Africa. It set up a federated South Africa with one white state and nine Bantustans and allocated all Africans to a supposed nationality group – Xhosa, Zulu, Tswana, Sotho etc., whether or not they had ever visited their so-called ‘homeland’. Africans had no rights in so-called white South Africa. Subsequently four of these Bantustans – Transkei, Ciskei, Venda and Bophuthatswana – were given spurious independence. The Bantustans were totally dependent on the white government for funding and were run by client elites hated by most of their supposed citizens.

Those living on the land as subsistence farmers were forcibly moved to the Bantustans and often dumped on the veld with basic housing and no facilities. It has been estimated that by 1983 3.5 million people had been uprooted.

Indians and ‘Coloureds’ had no land allocated to them. They were forcibly moved to segregated townships like Lenasia outside Johannesburg and Mitchell’s Plain in Cape Town.

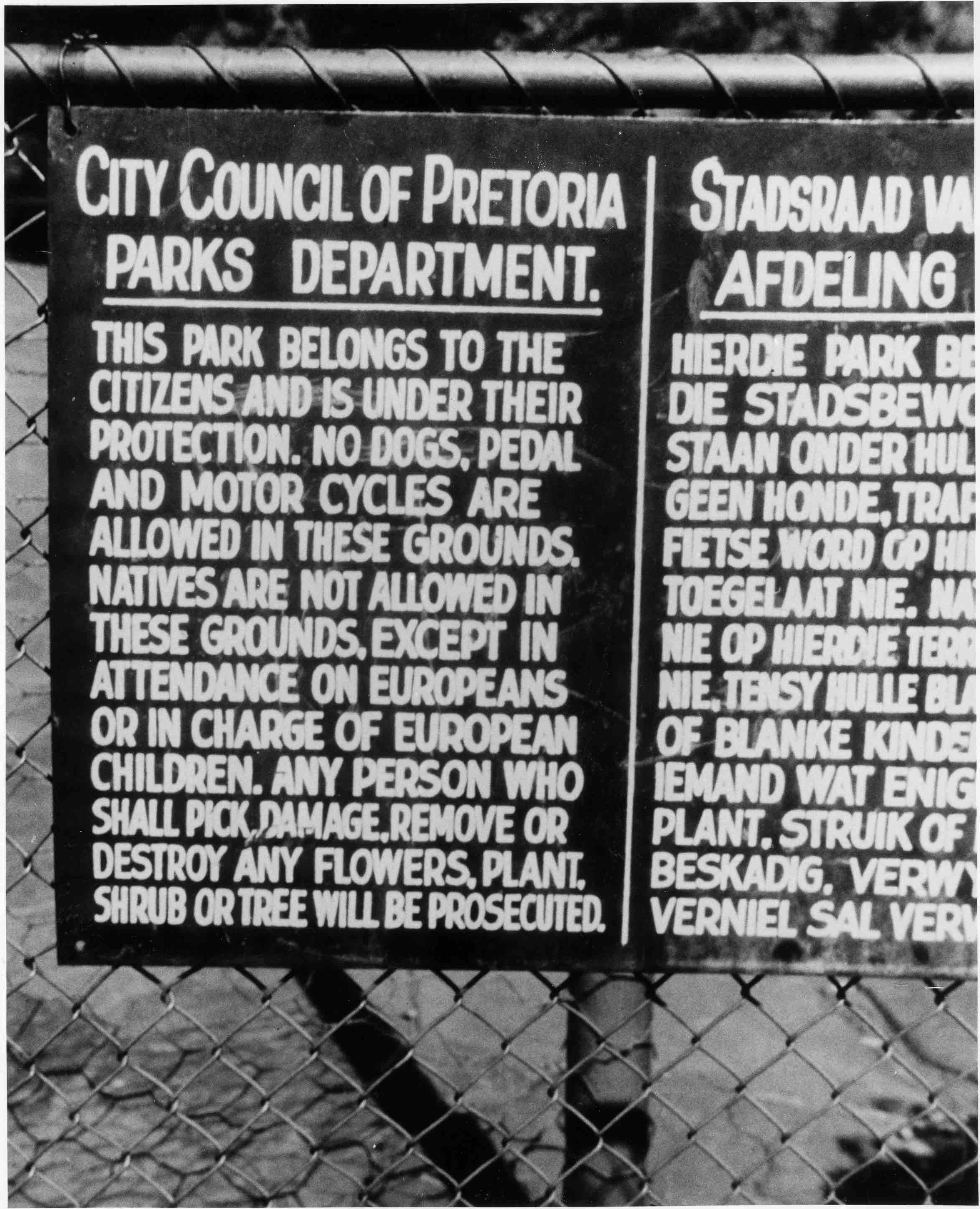

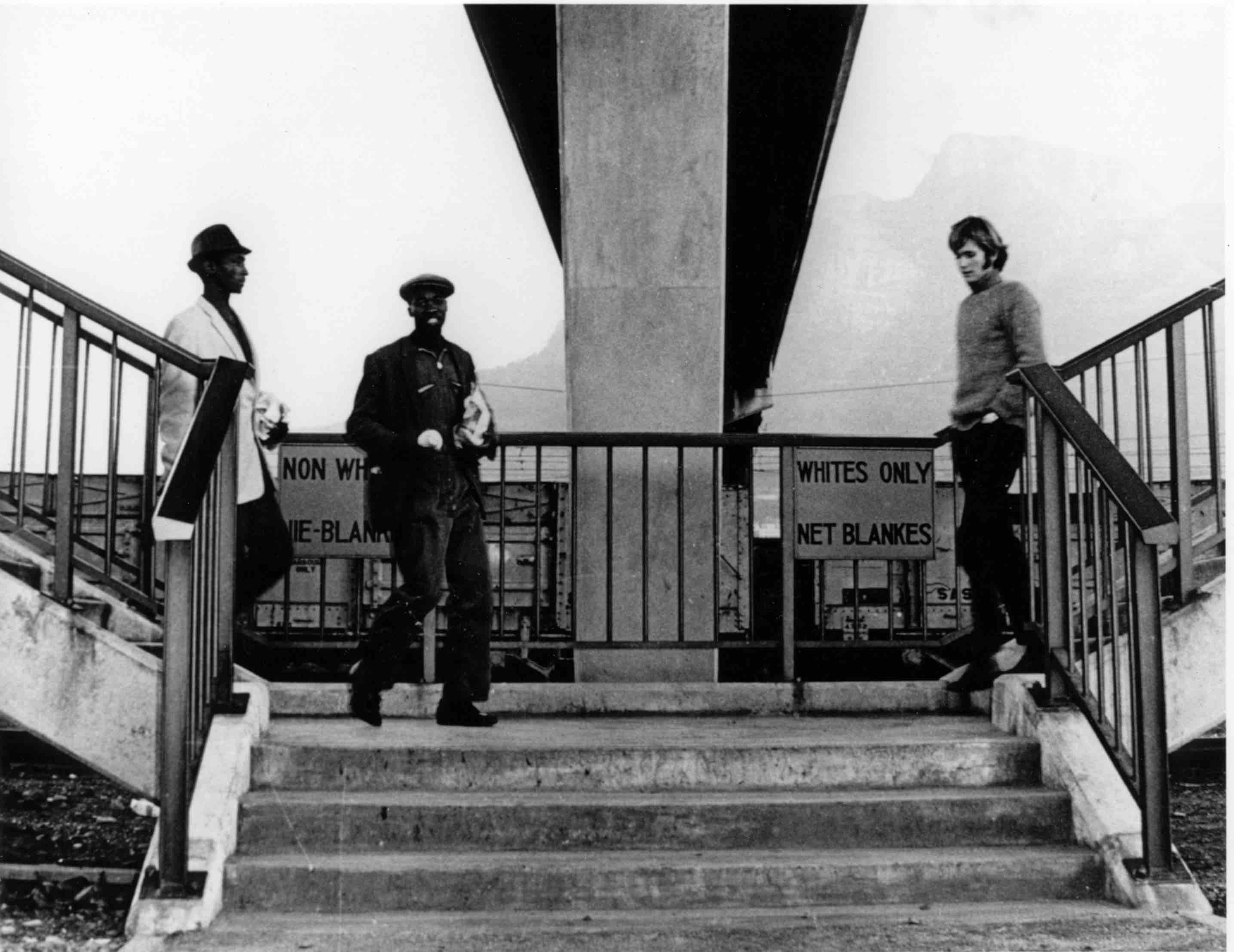

Interracial marriage and sex became illegal. Primary and secondary education under the Bantu Education Act became totally segregated. Higher education under the inappropriately titled Extension of University Education Act became almost entirely segregated. People were pushed out to townships outside the main city centres. In Johannesburg the migrant multiracial community of Sophiatown was bulldozed. Hospitals were segregated. Everyday life – transport, entrances to public buildings, parks – was strictly segregated.

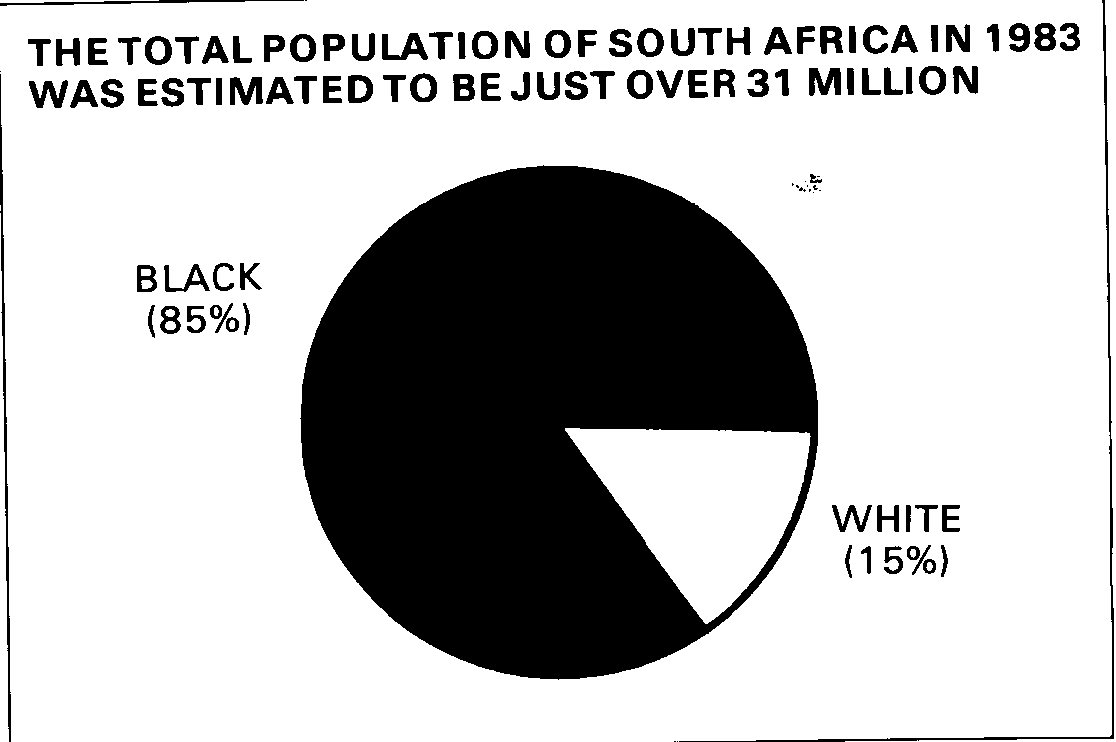

In spite of land segregation, hundreds of thousands of Africans lived in the new townships around the perimeters of the so-called white towns. In the major cities Africans still outnumbered whites by two to one. All apartheid did in the major towns was to move Africans out of the centre to under-resourced and overcrowded townships. But they were only allowed to live there as long as their labour was needed, and as long as they had an employer who would vouch for this. The movement of African workers was regulated by the pass laws and they had to carry their pass with them at all times. Every day thousands were arrested for not carrying their pass. It has been estimated that 12.5 million people were arrested between 1948 and 1981 for breaches of the pass laws. In addition to those who lived with their families in the townships, many were migrant workers who had been forced to leave their families behind in the rural areas, with consequent problems of alcoholism, violence and societal breakdown.

The crucial point was that – unlike in Israel – the whole economy was dependent on black labour. Whites had one of the highest standards of living in the world; with the industrial boom of the 1960s there were very few poor whites. Every sector depended on black labour: mining, manufacturing, agriculture, and domestic services. There was total job segregation and huge wage differentials. The government set up factories in the so-called border areas, adjacent to the Bantustans, but this involved big transport costs. As the manufacturing sector grew more Africans lived in the major conurbations.

Because of this by the 1980s the whole system was breaking down. And the economy needed more skilled labour – white immigration could not provide enough. This was one of the underlying causes of the Soweto uprising in 1976. In an attempt to provide more semi-skilled labour, the apartheid government tried to cram more young people into the existing schools – without spending more money to provide adequate school buildings, staffing levels and educational equipment. Coupled with the growth of black consciousness this was a tinder box ignited by the decision that more teaching would be conducted in Afrikaans.

Also in the 1970s workers once more started to organise, and in an attempt to contain the new unions the government changed the law – a move which badly backfired.

Repression on the other hand was horribly similar to that in Palestine. South Africa professed to have a rule of law. But under the 1967 Terrorism Act detainees could be held indefinitely in solitary confinement with no access to anyone from the outside world. As resistance grew, the government imposed States of Emergency in 1985 and 1986, and in the 1980s thousands were arbitrarily detained. As in the West Bank and Gaza it was young people who were protesting, and were being picked up and brutalised. In 1980s troops went into the townships teargassing and shooting people – in many ways like the atrocities in Gaza in recent weeks.

Throughout the apartheid period, South Africa depended, as does Israel, on the West – on the countries of Western Europe and the US. This support took the form, not of subventions and aid, but of trade and economic investment: this was absolutely crucial. In the 1960s it depended as well on Western countries for arms supplies and military knowhow. Western countries, including Britain, were very quick to denounce apartheid, but very slow to do anything about it. One significant success of the international solidarity movement at the UN was the mandatory arms embargo imposed in 1977, after the murder of Steve Biko and the banning of above ground organisations, including the Christian Institute, that couldn’t be characterised, as the South African government was quick to do with other groups, as Communist. And there is a lesson there, that the campaign for an arms embargo appealed to a much wider constituency than the campaign for boycott and sanctions.

Western governments only imposed sanctions really late on, in the 1980s, and very partial ones. In fact what happened was that the corporates moved out because South Africa was no longer economically attractive. This was because of a combination of internal unrest and the international campaign.

In the 1970s the situation in South Africa did seem almost hopeless. The South African government was intransigent, most South African whites – if not all – were racist and arrogant; the apartheid regime seemed impregnable. Anti-apartheid activists did not think the end was in sight. But they continued to campaign – and the inspiration for that came from knowing that situation of total injustice and that people resisting inside the country were suffering so much more than those who supported them from the outside.

But in the end it came quite quickly – although it was very difficult. So ultimately the message is one of hope. I am sure the same applies to Palestine and this perspective should inform our discussions today.

Watch the original speech given by Christabel Gurney at the link below.

1961: Albert Luthuli in Oslo.

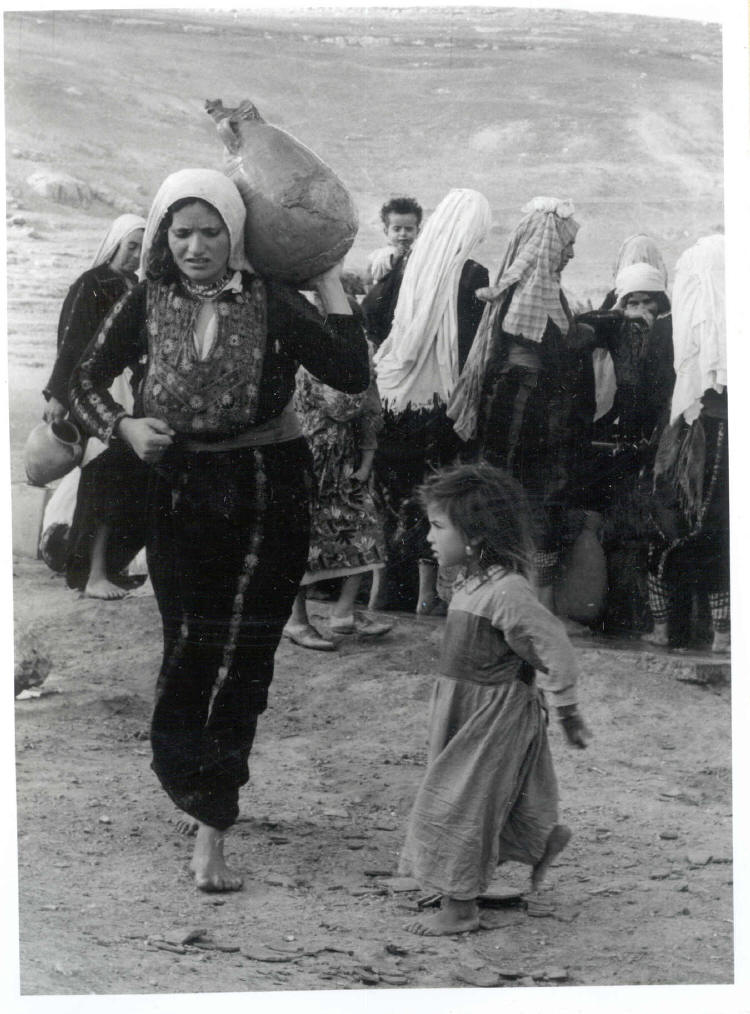

1948: Palestinian refugees.