Russian revolution and other revolts

By Gina Nicholson

The October Revolution was greeted with horror by the capitalist classes of the world and several armies were despatched in an attempt to defeat it. These armies included troops from Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania. France, Greece, United States, Estonia, Japan, Italy, Republic of China, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. In Britain, future British prime minister Winston Churchill, who served as war minister during much of the intervention in Russia, spoke of "strangling the Bolshevik baby in its crib."

That revolution was not a single isolated incident, but the most important and far-reaching element of a complex movement. The Russian people were not alone in rising up against the injustices of their rulers in 1917. A number of different but related causes led to mutinies, revolts and revolutions in many other countries across Europe.

First World War

The immediate cause was the war itself. Seventeen million died in the First World War, including seven million civilians. More than a million soldiers were wounded or killed in the battle of the Somme alone. A deep disgust arose not only with the killing but also with the glorification of war, as expressed in Wilfred Owen's poem, Dulce et Decorum Est.

Then there was the effect of the war on the standard of living of the mass of the people. There were serious shortages of food and other supplies due to the difficulty of trade in wartime. Then peace came and the armies were demobilised, adding to or creating unemployment. Germany, Austro-Hungary, Italy, France, Britain all suffered crippling surges in the cost of living. Even in Spain, for example, which was neutral in the war, the same suffering occurred.

The further development of industry in the nineteenth century, especially the spread of the railways, had vastly assisted communication between peoples, including the spread of socialist ideas and news of workers' struggles. And the development of capitalism itself, in which the growing working class felt the effects of increasing exploitation, had, even before the war began, given rise to powerful workers' struggles.

Finally, the ideas of communism, the spectre haunting Europe, had flourished.

Italy

The Italian Biennio Rosso (two red years) lasted from 1918 to 1920, involving strikes, mass demonstrations and factory occupations. More than a million industrial workers struck in 1918, even more the following year. Many factories were occupied. On July 20-21, 1919, a general strike was called in solidarity with the Russian Revolution.

Turin metal-workers struck in April 1920, demanding recognition for their 'factory councils', which were seen as the models for a new democratically controlled economy running industrial plants, rather than as a bargaining tool with employers. Armed metal workers in Milan and Turin occupied their factories in response to a lockout by the employers. Factory occupations swept the "industrial triangle" of north-western Italy. By September 3, 185 metal-working factories in Turin had been occupied.

By 1921, the movement was declining due to an industrial crisis that resulted in massive layoffs and wage cuts. The revolutionary period was followed by the violent reaction of the Fascist blackshirts militia and eventually by the Mussolini's March on Rome in October 1922.

Germany

In war-weary Germany, two admirals decided without authorisation to send the Imperial Fleet to engage the British Navy on 24 October 1918 - and the sailors mutinied. The spark fell on tinder-dry ground, and the slogan 'Peace and Bread' was raised. Around 4 November, delegations of the mutinous sailors dispersed to all of the major cities in Germany. By 7 November, the revolution had seized all large coastal cities as well as Hanover, Brunswick, Frankfurt and Munich. In Munich, a "Workers' and Soldiers' Council" forced the last King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, to abdicate. In the following days, the dynastic rulers of all the other German states had abdicated.

On 9 November, a group of 100 Revolutionary Stewards from the larger Berlin factories occupied the Reichstag and formed a revolutionary parliament.

Workers' and Soldiers' councils were established quickly, almost entirely controlled by social democrats (the SPD and the USPD). They took away power from the military commands but there were almost no confiscations of property or factory occupations. The leadership of the SPD were concerned to prevent a genuine social revolution and demanded elections for a national assembly.

There followed a struggle between revolutionary (but divided) elements and those who wished to avert a social revolution. The January Revolt at the beginning of 1919 called for the overthrow of the social democratic government but failed to win over the troops and was brutally quelled at a cost of 156 lives. Following this the alleged leaders of the January Revolt had to go into hiding, but Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebnecht (leading members of the newly formed Communist Party) refused to leave Berlin, were discovered, arrested and brutally murdered.

Following this some Council Republics were proclaimed, a wave of strikes amounting to a general strike took place and escalated into street fighting in Berlin. The strikers were attacked by the Freikorps, which killed about 1200 people. There was virtual civil war in Hamburg and Thuringia. The last council government to be toppled, on 2 May, was the Munich Soviet Republic.

In 1919 a new Constitution was written and adopted in the city of Weimar, from which the Republic got its unofficial name. It lasted until 1933.

Hungary and Finland

The Hungarian Soviet Republic was a short-lived independent communist state which lasted from 21 March to 1 August 1919, led by Bela Kun. It was the second socialist state in the world to be formed after the October Revolution in Russia.

The Finnish civil war was lost by the Reds (social-democratic peasant and worker paramilitaries) in May 1918.

France

In France, war-weariness, unemployment and the high cost of living contributed to 'the rising wave of strikes and the huge workers' demonstrations for bread and progress, against Clemenceau's military dictatorship and against the military intervention in Russia.' (Andre Marty, The Epic of the Black Sea Revolt). The news of this filtered through to the soldiers and sailors despite press censorship.

On 11 November 1918 the armistice was signed and the mass of the people, particularly the soldiers, looked forward to peace. However on 18 December a French army division landed at Odessa where the French fought beside the Russian White Guards against Ukrainian soldiers. The French soldiers and sailors were dismayed; they had thought the war was over but they were still fighting, and against a workers' republic. In this situation the Bolsheviks made headway with their pamphlets and newspapers, published in French, which, Marty comments, 'were eagerly accepted and read' because they 'displayed a remarkable knowledge of the situation and the everyday needs and demands of the French soldiers and sailors.' The Bolsheviks thus managed to counter the propaganda spread by the French commanders, which portrayed the revolutionaries as criminals, child-eaters and rapists, and to explain the significance of the Revolution.

By February, 1919 there was serious agitation in the ranks of the French army; and towards the end of March the army was partially neutralised.

First, soldiers refused to march. A battalion of infantry was supposed to seize Tiraspol but as soon as the guns began firing the battalion fell back, taking along the artillery and cutting telephone communications. The men were disarmed and evacuated to Morocco. Then two companies of infantry refused to march to Kherson. Marty comments: 'They disorganised the front . . . and thereby made it easier for the Red detachments to capture the city.' There were many similar incidents.

Then a company of Engineers drove away their officers and gave their arms to the (Soviet) workers. Odessa was evacuated on April 5, with whole French units singing the Internationale. The officers generally fled. 'The French army had turned into a disorganised throng with every trace of military discipline gone. It became necessary to send it back to France.'

Finally came the sailors' mutinies

Andre Marty was chief engineer on board the destroyer Protet, at Galatz in Romania. He and a number of others had planned to seize the ship and take her to Odessa to join the revolution, but this plan was betrayed by spies and Marty and three others were arrested on April 16. Three days later a revolt broke out upon the battleship France, lying off Sevastopol, where the ship had been shelling the Red Army soldiers as they approached the city. The next day the crews of the sister ships - the France and the Jean-Bart (the Admiral's flagship) gathered on deck, sang the Internationale and hoisted the red flag. The troops which had landed from these ships abandoned their positions and proceeded to the shore. The sailors threw their ammunition boxes into the sea. The warships were forced to sail for France.

Marty, imprisoned on the cruiser Waldeck-Rousseau, made contact with the crew and on April 27 they too mutinied, imprisoned their officers and took over the radio. The ship left Odessa and sailed for France.

For three months similar mutinies and demonstrations occurred on all the warships in the Black Sea. The blockade of Odessa was broken.

As the warships returned to France, information about the Russian revolution and the mutinies began to spread. Committees of sailors were formed almost everywhere. In Toulon the crew of the battleship Provence, and of the battleship Voltaire at Bizerte in North Africa refused to sail for the Black Sea. The unrest spread to Itea in Greece and to Vladivostock. Everywhere sailors were demonstrating.

The French government were forced to demobilise the army, disarm the warships and recall all forces of intervention from Russia.

Britain and the Hands off Russia campaign

Although Marty sourly remarked that 'the British bankers and lords, as has always been their custom, let others do their fighting for them,' in fact a Royal Navy squadron, consisting of cruisers and destroyers, was sent to the Baltic in 1918, the commander of which, Rear-Admiral Edwyn Alexander Sinclair, promised to attack the Bolsheviks 'as far as my guns can reach'; British troops landed at Archangel and Baku; and a British Empire force including Canadian, Australian and Indian troops, also intervened in Russia.

In Britain an unprecedented period of militancy, strikes and trade union development had been interrupted by the start of the imperialist war, and thousands of workers had enlisted, drawn by war's 'terrible attraction . . . the wild excitement, the illusion of wonderful adventure and the actual break in the deadly monotony of working-class life.' (William Gallacher, Revolt on the Clyde). But while the official leadership supported the war, a new tendency began to grow among working-class organisations which opposed the war on political grounds.

Having sent hundreds of thousands of workers to the front, the employers were short of labour in a period which demanded increased production, particularly of munitions. Therefore exploitation increased. In a few cases wages were increased, but as the war continued prices rose faster than wages and the working class suffered while the employers made huge profits - which were 'estimated to have increased by £4,000 million during and owing to the war.' (Morton and Tate, The British Labour Movement). Indeed the suspicion that profit was the main motive for the war grew, not only among the workers. The poet Siegfried Sassoon, a young officer decorated for bravery, wrote an open letter of protest to the war department, refusing to fight any more. "I believe that this War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it," he wrote.

The labour movement, notably the rank and file, recovered from the pause the war had brought. There were big wartime strikes, first of the South Wales miners and the Clyde engineers in 1915. The Clyde strike gave birth to the Clyde Worker' Committee (at first called the Labour Withholding Committee) which was 'pledged to resist the Munitions Act, support of which by the union officials its initial manifesto stigmatised as "an act of treachery to the working class"'. (Allen Hutt, The Post-war History of the British Working Class).

Boilermakers in Southampton struck in September 1915 in defence of trade union conditions; In the new aircraft industry, a national committee was set up which forced concessions in November 1917 from the then Minister of Munitions, Winston Churchill.

Hutt remarks:'Trade union membership mounted rapidly as the war continued. In 1913 the Trade Union Congress counted less than 2¼ million affiliated members; in 1918 over 4½ million were in its ranks.'

Not just trade union militancy but a growing socialist consciousness characterised the movement. Â Particularly in Glasgow was this the case, where the Marxist agitator and educator John McLean was extremely active and very popular among the workers. With the Russian revolutions of February and October 1917, came an upsurge of delight, confidence and clarity among the working class.

William Paul, in his pamphlet 'Hands Off Russia', warned: '...the ruling class, which has been unable to defeat Socialism intellectually in the domain of ideas, is now attempting to defeat a Socialist Government in Russia with such weapons as the blockade, starvation, assassination, spies, corruption, and armed naval and military forces . . .'

In August 1918 the Metropolitan police struck, to the consternation of the government. All their demands were met except union recognition, but since the government negotiated with the union leaders this amounted to de facto recognition. When the Manchester police threatened to strike they also secured their demands.

In 1918 there had been mutinies at the British army camps in France. By 1919 the army was in ferment. The government was slow to demobilise, having an eye on events in Russia and the possibility of intervention, but the conscript soldiers were in no mood for that. There were mutinies at Folkestone, Dover, Brighton, Salisbury Plain and Isleworth. Thousands of troops arrived in London voicing their demands. Effectively this movement prevented the use of conscript troops in Russia- but there was little or no contact with the organised working class.

1919 was a peak year for strikes. Workers on Clydeside struck for a forty-hour week, and when a peaceful demonstration in George Square was attacked by police the workers routed their attackers. The miners struck, demanding a wage increase, a six-hour day and nationalisation of the mines. This strike was defeated by government duplicity but he battle continued on other fronts. 300,000 Lancashire cotton workers staged a successful strike for a wage increase and a forty-eight hour week.

The railwaymen had been in negotiations which the government deliberately dragged out, and then made a 'definitive offer' demanding cuts - a clear provocation. The railwaymen struck, and despite an attempt to buy off the locomotive men, the strike was solid. The government caused the strike pay to be withheld and leaked plans to starve the strikers into submission. The Co-operative movement made strike pay available and accepted vouchers from strike committees for food. The London newspaper workers- compositors and machine-men - refused to set or print newspapers until the railwaymen's case was fairly put. The NUR entrusted the task of publicity to the Labour Research Department, which rose magnificently to the task.

By the end of a week, the strikers had won.

In London the young Harry Pollitt had taken up work as a boilermaker and was thus in a good position to pursue political work among the dockworkers. In the summer of 1919 the 'Hands off Russia' movement was formed as a response to the military attacks on the young Soviet republic and the stream of 'filthy propaganda' poured out by the press in Britain.

On August 6 the British government issued a 'Declaration to Russian Peoples', stating that they had 'no intention of interfering in Russian polities', but the actions of the British military authorities and their support of anti-Soviet forces indicated otherwise. British troops had landed at Archangel in the north and in the south at Baku. The British government was sending arms to Poland to support that country's anti-Soviet efforts.

On May 10th 1920, the same day that the Polish army captured Kiev, the London dockers refused to load arms marked for Poland on the ship the Jolly George. The coal-heavers refused to coal the ship. The owners were forced to back down.

It was a relatively small victory but it electrified the entire British labour movement. A week later the Dockers' Union banned the loading of any arms for use against Russia. A motion was put to the Labour Party Conference proposing a general strike. While this motion was not passed, it nevertheless became the policy of the movement.

Then the Polish army was beaten back by the Red Army to the gates of Warsaw. Seriously alarmed, on the 3rd of August the British government threatened war against Russia.

On Wednesday 4th August the Labour Party headquarters telegraphed all local labour parties and trades councils urging that demonstrations against war on Russia be held the following Sunday, August 8th. The Daily Herald newspaper came out with the headline 'Not a man, not a gun, not a sou'.'The demonstrations broke all records.' (Allen Hutt). The Labour Party executive reported that it was 'one of the most striking examples of Labour unity, determination and enthusiasm in the history of the movement.'

Following this a joint meeting of the Labour Party (including MPs) and the T.U.C. set up a Council of Action to implement the policy against war on Russia. It was authorised to call for 'any and every form of withdrawal of labou' which might be required. Three hundred and fifty local Councils of Labour were set up. Every major city and town was covered. Telegrams were sent to the workers of France and Italy, inviting them to join in the proposed strike.

The British government 'surrendered unconditionally. It advised the Polish government to cease its military actions against Russia . . .' (Morton and Tate).

Lenin commented: 'This Council of Action, independently of Parliament, presents an ultimatum to the Government in the name of the workers - it is the transition to the workers' dictatorship . . . The whole of the English bourgeois press wrote that the Councils of Action were Soviets. And they were right.'

In Britain the capitalists feared a revolution but it didn't happen. When the worker' demonstration in Glasgow's George Square beat back the attacking police, troops from the south were sent to maintain order, because the Scottish conscript soldiers could not be trusted to go against their own people. But it did not even occur to the workers’ leaders on the Clyde to make common cause with them. William Gallacher remarked,'We were carrying on a strike when we ought to have been making a revolution.'

In most countries in Europe, some of the requisites for revolution were present. Large sections of the working class were engaged in determined struggle for their own conditions and in defence of the workers' revolution in Russia. Workers, soldiers and sailors, acting together or separately, forced the capitalists to give up their attacks on the young Soviet state. But the revolutionary forces were disunited, and there was no organization yet capable of uniting and leading the working class to a lasting victory, despite heroic efforts in a number of countries.

Rosa Luxemburg

Karl Liebnecht

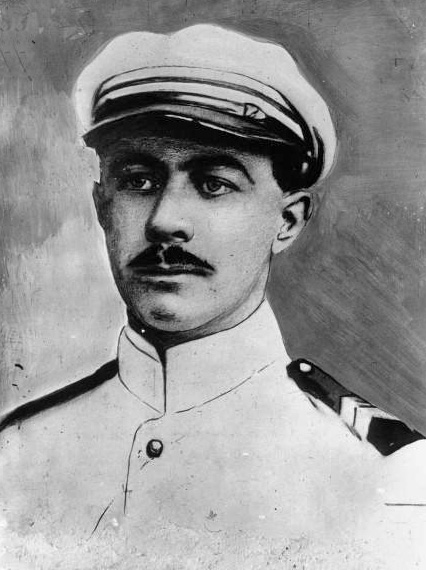

Andre Marty

Lenin

William Gallacher

Harry Pollitt addressing a meeting of workers