Options for a soft Brexit fall short

By Simon Korner

Both Labour and Tory positions on the Customs Union are effectively Remain, keeping Britain tied to the EU and subject to its undemocratic constraints.

In February 2018, The Guardian lavished unusual praise on Jeremy Corbyn after Labour announced it would seek ‘a’ customs union with the EU. Corbyn, said The Guardian editorial, understands that “if Britain wants a close trading relationship with the EU, it has to cleave to EU standards… He knows that EU rules have become global standards and UK industries will wish to follow them. Thus Labour, sensibly, accepts EU jurisdiction over the production and trade of goods…”

Labour’s position contains one key caveat, however. According to Corbyn:

“A new customs arrangement would depend on Britain being able to negotiate agreement of new trade deals in our national interest. Labour would not countenance a deal that left Britain as a passive recipient of rules decided elsewhere by others. That would mean ending up as mere rule takers.”

But is Corbyn’s position viable? Could his “customs arrangement” allow Britain a say in making the rules? According to pro-business thinktank Open Europe, “Labour is seeking an unprecedented solution that would be extremely difficult to negotiate.”

Before discussing this further, a brief explanation of the Customs Union is needed – how it relates to the Single Market and how it differs from a free trade agreement.

CUSTOMS UNION AND SINGLE MARKET

The EU Customs Union underpins the EU Single Market. The Single Market is a unified European trading bloc with an internal market, in which all economic rules and regulations are the same for the 28 countries within it. These rules govern what governments can and cannot do in terms of subsidising domestic industries and using public procurement and public ownership to guide the economy strategically. The main aim of the Single Market or internal market is to promote a competitive marketplace, rather than allowing socialist or even social democratic elements of planning that exclude the private sector – it is a capitalist club.

The external borders of the Single Market are like a tollgate, extracting tariffs (taxes) on goods entering the internal market. The borders also ensure that non-tariff rules are obeyed – such as food standards and health and safety.

The policing of the external borders of the EU is the job of the Customs Union. Customs restrictions are identical anywhere on the EU borders. So if a Chinese product enters the Customs Union through Britain, the tariffs collected on it are the same as if it had entered through France or Spain or Italy. Once inside, the product can circulate freely to any EU country, with no internal tariffs or customs.

The same goes for any goods or services produced within member states – they too can circulate freely. Thus, a car made in Germany can be exported to Britain, or vice versa, with no charges or checks, as if it were being sent to another part of the same country.

The Customs Union is an important element in the integration of the EU economies, allowing the bloc to act as one in terms of trade.

Without such rigid uniformity of tariffs, outside countries trading with the EU could find a member state with low tariff barriers and penetrate the EU through that weak point, without paying the agreed EU rate. This would create unfair competition between EU member states and compromise the whole system, which works as a sealed unit.

The uniform position on tariffs also means that no single member of the Customs Union can make its own trade deals – which are basically all about tariff reductions. The terms of all EU trade deals with countries outside the bloc are set by the Customs Union – which is ruled by the European Commission – and cover all members.

Because of this high degree of control, customs unions are rare between large economies – which normally use trade deals as a form of competition. Most of the existing customs unions exist between small states and a neighbouring larger state, for instance, between South Africa and its poorer neighbours Swaziland, Namibia, Botswana and Lesotho. But the EU is an anomaly, arising out of the French attempt to suppress German power after World War 2 and later designed to allow a reunified Germany greater domination.

More usual arrangements between major countries are free trade agreements like Nafta, between the US, Mexico and Canada, or Ceta, between the EU and Canada.

FREE TRADE AREAS

Within a free trade area, tariffs are abolished between the member countries – hence ‘free’ trade. In this respect a free trade area resembles a customs union. But the difference is that a country within a free trade area can set its own tariffs on goods from countries outside the area. There is no uniform tariff for member states’ trade with external countries.

This freedom means that cross-border checks are necessary. This is to ensure that products from outside the free trade area are not pretending to be made within the free trade area – and thus exempt from tariffs. Without such checks, importers could bring in products to the free trade area through the member country with the lowest external rates. These products would then be cheaper and undercut the competition.

Border controls, while necessary to protect the free trade area, can be relatively frictionless, as with USA-Canada.

So, while both customs union and free trade options for Britain outside the EU would mean no tariffs on imports and exports to and from the EU, a free trade agreement would allow some flexibility in terms of trade agreements with non-EU countries, such as the BRICS or developing world.

Free trade agreements also do not intervene in the domestic markets of the member states. State aid, subsidies to industries, nationalisation are all permitted, so long as exported products conform to the rules of the free trade area. By contrast, the Customs Union determines all internal regulations, with the aim of allowing any EU company to penetrate any member country’s market. Free trade agreements regulate trade between member states but not trade with countries outside the area.

The most obvious free trade area for Britain to join after Brexit would be the European Free Trade Agreement (EFTA), which currently consists of Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland. Britain was originally an EFTA member before joining the EU. This area effectively comes under EU trade law – including free movement of people – because of the EU’s free trade agreement with EFTA through the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement. Thus EFTA member states are highly regulated, in return for access to the Single Market. The EFTA court which settles disputes is not really independent as its decisions mirror those made by the EU Commission and the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

The other option for Britain post-Brexit would be to join Ceta, the EU-Canada free trade agreement (more on which below).

LABOUR'S PROPOSALS

Under Labour’s proposed “new customs arrangement”, Britain would agree to impose the same EU tariffs and regulations that currently exist within the Customs Union. At the same time, because Britain would then be outside the EU, it would relinquish any say on EU trade deals made with external countries. The quid pro quo would be the maintenance of easy access to the EU internal market.

That would mean not being able to “negotiate new trade deals”, despite Labour’s claims that this would be possible. It would also mean keeping EU-devised tariffs, which serve Britain badly at present, such as the high tariff – and consequent high consumer prices – on oranges imported from countries like Morocco, which are outside the EU, to protect the interests of Spanish orange growers.

Labour’s plan would also mean continuing to collect EU tariffs on products entering Britain from outside the EU, with this money going into the common EU pot. This tariff-sharing is part of the system of freely circulating goods within the Customs Union, but it disadvantages Britain, because Britain has the highest level of exports outside the EU of all EU countries – roughly a 60-40 ratio of external to EU trade, compared to, say, France’s 40-60 ratio. Restrictions on external trade thus hit Britain hardest, while free-circulation has fewer benefits.

Belonging to ‘a’ customs union would also make Britain vulnerable to a TTIP-like deal in future. Ceta, the free-trade deal being signed between the EU and Canada, will become “a backdoor for TTIP” to re-emerge, according to War on Want, and is “set to undermine our democracy and destroy our basic rights”, with public services privatised en masse.

Like TTIP, Ceta will allow corporations to sue governments that restrict their ability to make profits. Like TTIP, Ceta will give tariff-free access to British markets without any reciprocal deal. Negotiations between the EU and Canada have been conducted in secret, with no scrutiny by MPs or MEPs.

If Britain is aligned to the Customs Union, Ceta’s rules will apply to Britain – which will have no veto in stopping such a deal going ahead. There is even a danger, if Ceta is passed before Brexit, that a hard Brexit would leave Britain entangled in the deal – which is precisely what Tory Brexiters want, but which Lexiters should resist.

Turkey’s position provides some interesting lessons for Labour.

Turkey is not in the EU. Nor is it in the Single Market, but it is in ‘a’ customs union with the EU, one that excludes agricultural goods and services. Turkey has no decision-making powers on deals the EU makes. It has to “align itself with Common Customs Tariff” and “adjust its customs tariff whenever necessary to take account of changes in the Common Customs Tariff”. It also has to follow any future changes in EU rules, to stay aligned.

In addition, it has to ‘harmonise’ any trade deals it makes with countries outside the EU with policy set by the European Commission. This effectively bars it from making external trade deals.

Turkey is obliged to grant tariff-free access to goods from any country with which the EU has negotiated a free trade agreement, without having a vote or a say in the negotiations. And it has no reciprocal rights to tariff-free access to that country. In addition, it still has border checks, as it is not party to free movement of persons.

The only concession to Turkey from the EU has been a ‘Turkey clause’ in which EU trading partners are encouraged to make deals with Turkey similar to the ones they make with the EU.

All of this makes Turkey clearly a rule-taker – which it has been willing to be as part of its longer term strategy of joining the EU and entering the Single Market.

Britain might be in a stronger position than Turkey to cut a better deal, given its bigger economy. But the very nature of a customs union means that bespoke variations by different members of the union threaten the union’s whole purpose, which is to act like a single country in terms of tariffs and other non-tariff regulations. For this reason, Labour’s ‘customs arrangement’ with “a meaningful say” in future deals is effectively impossible.

Overall, Labour’s position for a customs union and for access to the Single Market – no doubt reflecting the party’s divided membership and the strong Remain sentiment within the trade unions and the PLP – is a self-defeating position, severely weakening the hand of any future left-led government to act independently on trade. Even if the Labour leadership has been forced tactically into ‘constructive ambiguity’ on the EU, leftwing activists need not feel so constrained.

THE TORIES AND THE CUSTOMS UNION

Meanwhile, Tory divisions over Brexit were temporarily resolved through an inner-party truce agreed at Chequers earlier this summer, though not for long.

The Financial Times described the agreement as a “pro-business plan to keep Britain intimately bound to the EU single market and customs union, beating back Eurosceptic cabinet opposition to her new ‘soft’ Brexit strategy.”

It includes a “non-regression” clause, which would write into any withdrawal treaty a prohibition on future nationalisation and state subsidies. This aims to allay one of the EU’s main fears, that a future Labour government might threaten the profits of EU investors in Britain’s privatised utilities and transport if these industries were nationalised.

In terms of customs, Theresa May’s plan for a “facilitated customs arrangement” would be a different kind of soft Brexit from Labour’s. It would allow Britain to set its own tariffs at its borders, rather than applying the Customs Union tariffs as at present. But Britain would still remain part of a “combined customs territory” with the EU – which would mean that though its own tariffs would apply to goods coming into the UK, Customs Union tariffs would be charged and collected for goods destined for the EU.

May’s fudge is an attempt to give Britain an independent trade policy while at the same time acting “as if” it is part of the Customs Union.

The deal would agree a “UK-EU free trade area” based on EU rules covering manufacture and agricultural goods. There would be no free trade on services and therefore no “regulatory alignment” with the EU on these, and no subjection to future regulations. This would mean the City would no longer be automatically “passported” to sell its financial services to EU customers, but it would also be freed from EU restrictions. May’s aim is to appease both sides of her party to hold it together, offering a vision of a full Brexit in the longer term.

In spite of the “non-regression clause”, it is unlikely the EU will accept such a deal because any dilution of the Customs Union would begin a stampede of other member states demanding relaxations, and the union would dissolve.

Tory Brexiters won’t accept it either, as they see it as kicking Brexit into the long grass by submitting to European Commission and European Court of Justice rules on goods destined for the EU.

WORLD TRADE ORGANISATION (WTO) OPTION

So, if a customs union and free trade deal effectively tie Britain to the EU, what about a “hard” no-deal Brexit? The Tory Brexiters want a race to the bottom, with New Zealand-style radical deregulation and tax cuts. But could a no-deal Brexit open up space in a progressive direction?

Because WTO rules are in general laxer than the EU’s, Labour’s manifesto could be accommodated more easily under the WTO than in the EU or aligned to it, despite the dire warnings of the TUC and other Remainers of a no deal Brexit.

State aid is forbidden by the EU wherever it distorts competition, which is almost everywhere. So Labour’s plans for revitalising deindustrialised regions or creating national manufacturing champions, with capital channeled to where it is strategically needed, would be blocked if Britain remained aligned to the Customs Union and Single Market. Only small amounts of regional aid are allowed, as well as some exemptions from restrictions for certain areas such as renewables.

Under WTO rules, however, state aid is allowed because the WTO doesn’t cover domestic markets. The WTO only prohibits state aid if it affects international trade – for instance, by reducing imports from another country. Moreover, the WTO only acts if a country brings a case to its Disputes Settlements Mechanism. Countries flouting the rules can have duties imposed on them if by the complainant country. But the WTO doesn’t police state aid proposals before they’re enacted, as the EU does: it only lists subsidies it allows and those it doesn’t.

By contrast, the European Court of Justice is not only used by the EU but by domestic competitors to prevent rival industries receiving government subsidies. Labour’s manifesto plans – including setting up a National Investment Bank – would come up against ECJ rulings.

As for renationalising utilities, while nationalised industries exist in the EU, these have to act like private competitive companies and cannot be part of strategic national economic planning. They must follow the “market operator principle” and cannot be nationalised for strategic economic purposes, whereas WTO rules only apply to international trade.

The same goes for public procurement as a tool of industrial policy. EU rules on the “social value” of procurement policies – such as creating jobs or promoting ethical trade – apply narrowly to each particular contract, and cannot be used as part of a broader strategic economic plan. So a public procurement policy that prioritised the rights of workers, for instance, would not be allowed.

By contrast, the WTO would not prevent such a policy. The WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement sets out basic rules around discrimination, but these rules could be exceeded by a Labour government if it wanted to use procurement as a means of fighting pay inequality or supporting local jobs in particular areas. The WTO has made deals in several countries allowing help for SME’s, for example.

In conclusion, a hard Brexit would free Britain from EU domination, even if it offers no panacea. To prevent jumping from the EU frying pan into the fire of US domination, trade deals could be made with Russia and China and other countries outside Fortress Europe.

Remainers who regard the EU as a protective umbrella against catastrophic deregulation and impoverishment ignore the lessons of Greece, which suffered as a result of EU membership, and underestimate the powers a nation state has in resisting capital flight by overseas investors – through massive public investment and capital controls.

CUSTOMS UNION AND IRELAND

Finally, the fear that leaving the Customs Union and creating a hard border would undermine the 1998 Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement is unfounded. The Agreement does not prohibit customs duties and border checks on the border, so it would not be undermined by a controlled border. In any case, the frontier is already a legal border for alcohol, tobacco and fuel duty, immigration, visas, vehicles, dangerous goods and security. Customs would be added to this list, but mostly without need for physical infrastructure – some of which exists anyway.

Nor would Labour’s softer version of a customs union avoid a ‘hard’ border because, while tariffs might be lifted, non-tariff regulations would remain, as they do between Turkey and the EU. The choice is clear: either Britain stays in the EU or leaves. There is no halfway house.

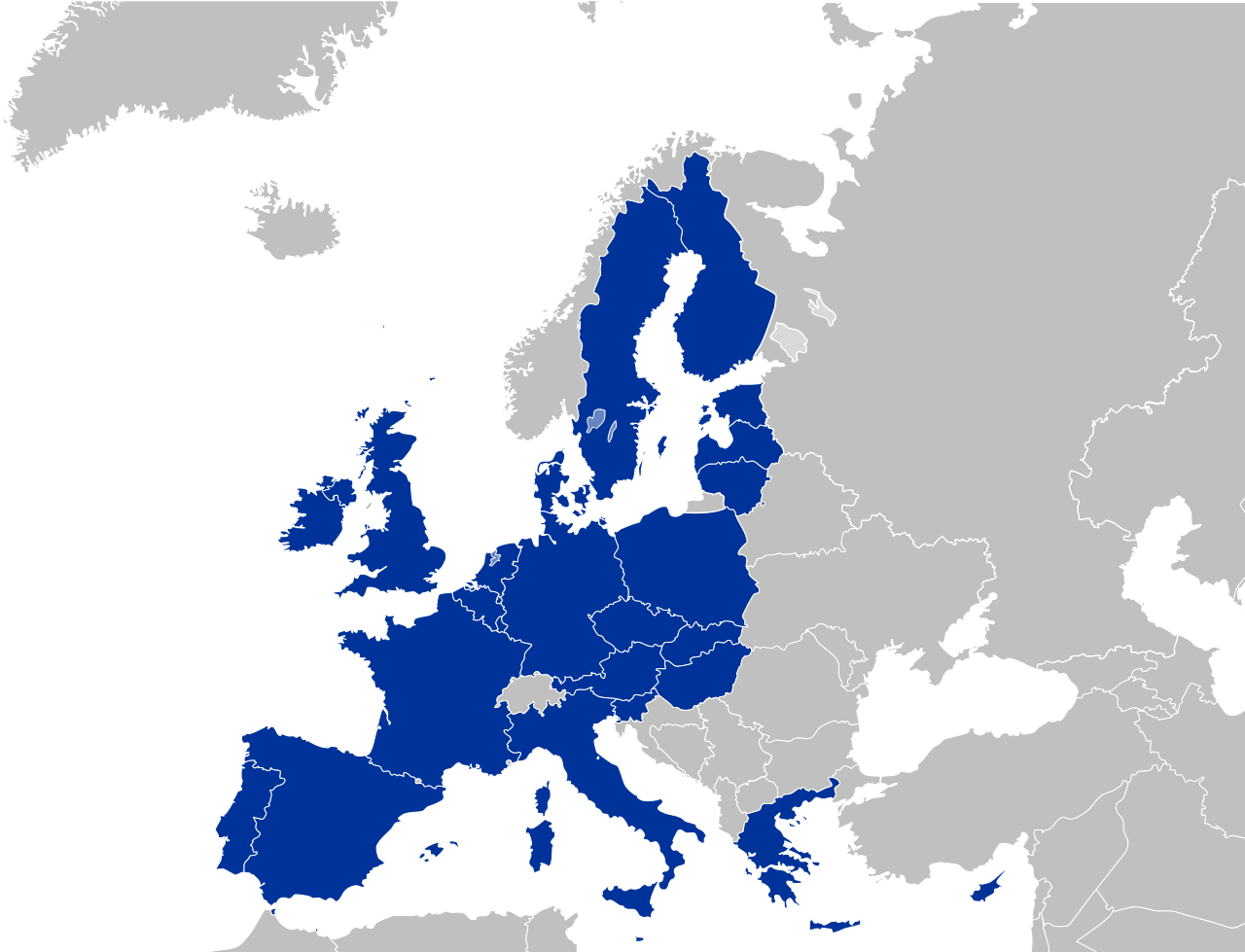

The European Customs Union

The Greek Port of Pireus privatised as a requirement of the Troika austerity package