Cyber warfare villains - Russia or the UK?

by Alex Mitchell

Britain is expected to ramp up its offensive cyber warfare capability in the face of alleged threats from Russia and China. Egged on by right-wing Tory MPs, the government is shifting focus from Islamist extremists to targeting its “strategic rivals”, with the new Labour leadership’s enthusiastic backing. The row over the delayed publication of a Parliamentary report on Russia has obscured the report’s main conclusion that the government should beef up its response to supposed hostile state meddling in British public life.

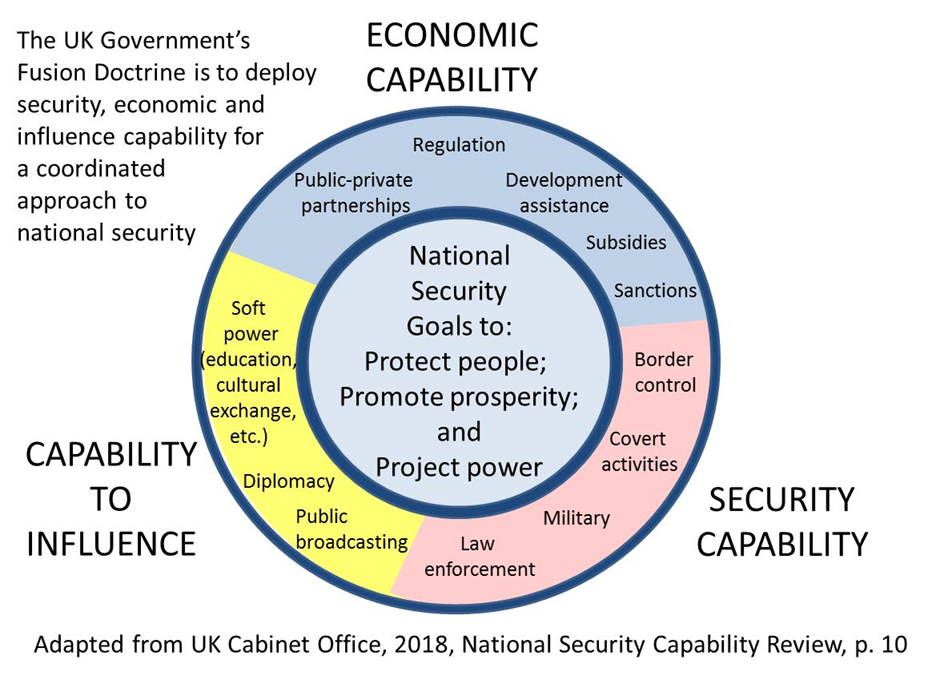

The summary report on the alleged threat from Russia prepared by Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee was published in July 2020 after a 17 month delay. The report recommended a coordinated strategy be adopted by government, including new legislation, to combat “hostile state activity”. The Committee backed a so-called Fusion Doctrine and a Whole-of-State Approach, whereby “security, economic and influence capabilities [are deployed] to protect, promote and project our national security, economic and influence goals”. (1) The word ‘influence’ has to be understood in relation to the neo-conservative theory that Western democracies are in competition with a range of anti-Western ideologies including Islamist ideas and illiberal and populist politics.

RUSSIAN MEDDLING - LACK OF EVIDENCE

The government’s reluctance to publish the Russia report aroused expectations that the Intelligence and Security Committee would reveal evidence about the Russian menace and uncover serious gaps in the UK’s defences. The Committee was indeed critical but this stemmed from its frustration that its enquiry had turned up so little. It was miffed in particular by the condescending attitude of the Security Service (MI5), which responded to the Committee’s call for evidence with a memorandum of six lines, and by the insubstantial testimony from other agencies, the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), the Home Office, Ministry of Defence and the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). This lack of proof of Russian maleficence, the Committee decided, was because the intelligence agencies had not looked for evidence hard enough.

It believed there was “credible commentary that Russia had tried to influence the 2014 Scottish independence referendum” and was “spreading disinformation through the internet to undermine trust in democracy and in democratic institutions”. (2) Shortly before the report was finally published, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab claimed that “Russian actors had almost certainly sought to interfere” in the 2019 election using illicitly acquired government documents. The claim was part of a Tory smear campaign against the Labour Party, while the evidence for the alleged meddling in the Scottish independence debate is unimpressive.

During the 2019 general election, Jeremy Corbyn used leaked government documents detailing the talks between the UK and the USA on a free trade agreement to prove that Washington wanted “total market access” for its companies to UK markets, including for health care and pharmaceutical products. Corbyn stated that the talks, which had been going on since 2017, “were at a very advanced stage” and that the documents showed that, contrary to Tory denials, “the NHS is on the table and up for sale”. The 451 page dossier from the Department for International Trade had been posted online on the Reddit website by ‘Wilbur Gregoratior’ on 23 October 2019, who Reddit (part of an American media group that also owns the Discovery TV channel) later claimed was based in Russia and was linked to “a disinformation campaign”. However, the dossier was itself undoubtedly genuine, having been obtained from a hack of the then International Trade Secretary, Liam Fox’s, personal email account. (3) Instead of defending the Party, Lisa Nandy, the shadow foreign secretary, in responding to Raab’s contention on the Andrew Marr show on 19 July 2020, said that neither she nor Labour leader Kier Starmer would have disclosed the leaked dossier if they had known it came from Russian agents. She went on to advocate sanctions on Russian and Chinese officials in retaliation for human rights violations against their own citizens.

Russian foreign ministry official Konstantin Kosachev described the parliamentary report’s conclusions as “unfounded, unsubstantiated and unconvincing”. Nevertheless, with most media commentary taking the allegations of meddling for granted, it is not surprising that an opinion poll revealed that nearly half the population believe that the Russian government has interfered with the 2016 EU referendum and the 2017 and 2019 general elections (by 49, 46 and 47 percent respectively). (4)

The claims made against Russia derive from a Cold War mindset that attributes almost everything said on Russian or Chinese social media to the Putin regime or the Chinese Communist Party. Former Conservative MP Dominic Grieve, who chaired the intelligence and Security Committee, claimed there was “growing evidence of Russia’s spreading of disinformation through the internet to undermine trust in democracy and in democratic institutions, as well as its covert attempts at exerting influence” in Britain’s public life. (5)

One of the Committee’s witnesses was the neo-conservative historian and columnist Anne Applebaum. We do not know the content of her testimony, but in articles for The Washington Post, she recalls how in the 1980s the USA “pushed back” at Soviet propaganda by assembling an inter-agency Active Measures Working Group to monitor the opinions of ordinary Soviet citizens and use these to gain traction for “a Western response” to destabilise and demoralise. “There is no systematic US or Western response to Russian, Chinese or Islamic State disinformation,” she averred. According to Applebaum, for two decades, the Russian government and companies controlled by Putin’s cronies have corrupted Western businesses and politicians to “undermine democracies” and “spread Russian authoritarianism” in Europe and the Middle East. Russia’s goals “are to weaken the European Union, soften up NATO and make the European continent safe for corrupt Russian money.” (6)

The claim that the Kremlin has an agenda to spread disinformation in order to undermine trust in democracy is mistaken. The Western narrative portrays Russia as its antagonistic ‘other’, belying the true complexity of their relationships. Sociologist Lilia Shevtsova considers that “the key factor in the West’s misperception of Russia is a determination to see only a single, dominant trend, which does not exist.” (7) It results from a continuing Cold War mentality.

Russian foreign policy goals are openly stated. In 2016, Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister, explained that NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe had undermined the chance of establishing a secure foundation for European security. It had created “a new subjugation” whereby the new NATO member states could no longer take important decisions without the say so of Brussels or Washington. (8) Moreover, Russians are far from being alone in pointing out the hypocrisy of some politicians in Western Europe and North America, who talk so much about democracy and the rule of law while they wage war in other peoples’ countries. The pot should take care before calling the kettle black.

Furthermore, the views aired on Russian social media come in all shapes and sizes. There is considerable commentary on international affairs from a variety of political perspectives, just as there is in English language social media.

The Scottish independence referendum aroused the interest of Russians because the issues mirrored debate within the Russian-speaking community about the rights of a people to declare independence. In early 2014, many people in Crimea and the Donbass pushed to secede from Ukraine and to re-join Russia. Volunteer troops from Russia were despatched to these provinces and fighting ensued between them and the Ukrainian armed forces and irregular fascist militia. Secessionist uprisings were put down by the Ukrainian authorities in Kharkov and Odessa but Crimea and much of the Donbass broke away. A large majority of Russians supported these actions and thus there was exceptional interest in the debates going on at the same time in Scotland and in Veneto, where an unofficial plebiscite was organised on independence from Italy. A non-binding referendum was also held in Catalonia later in the same year. The debates on Russian social media in 2014 spilled over from more local concerns to the rights of regions with their own traditions to autonomy.

By contrast, Russian social media commentary on the EU debate in Britain attracted less interest and was more balanced in terms of what the result might entail for the Russian Federation. Russian posts reflect Russian attitudes and these can make for uncomfortable reading for those unfamiliar with their national context. For example, a Russian blogger might cheer the annexation of Crimea and Scottish or Venetian independence yet condemn the secession of Chechnya and basing laws upon the Sharia. Regrettably, some commentators use racist and disparaging slurs when posting on world events, not so different from the vehement tone adopted by many in the West. Be that as it may, the spill-over from Russian debates accounts for the impression that “Russian actors” attempted to influence the Scottish referendum and it also explains why evidence is lacking for a similar degree of “meddling” in the EU referendum and subsequent UK general elections.

Media commentary does not take place in a regulated arena, of course, and governments, corporations and rich business people attempt to shape the discussion in their own interests. It includes fanning hype on social media by re-posting comments to amplify the message. Even Anne Applebaum has admitted that “a shutdown of Russian bots will still leave swarms of American bots free to deceive American voters. By its very nature, social media makes disinformation campaigns possible on a larger scale than ever before.” (9)

EVIDENCE OF WESTERN MEDDLING

Although the Intelligence and Security Committee were patently unhappy with the intelligence agencies’ condescending attitude towards its investigation, its recommendations are sure to be adopted. Certain of those recommendations received no publicity in the national press but they reflect the assertions made by Anne Applebaum that the Kremlin’s threat to democracy must be countered actively, just as the West sought to do during the Cold War against the USSR.

“The UK, as a Western democracy, cannot allow Russia to flout the rules-based international order without there being commensurate consequences,” the Committee stated. “The Kremlin has shown a willingness and ability to operate globally to undermine the West, seeking out division and intimidating those who appear isolated from the international community. The West is strongest when acting in coalition” and such cooperation should seek to “attach a cost to Putin’s actions.” Britain should therefore work closely with its Five Eyes intelligence partners (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, USA and UK) and NATO, including “the NATO Intelligence Fusion Cell at RAF Molesworth”. (10)

Formerly a nuclear-armed cruise missile base run by the US Air Force, RAF Molesworth was re-designated as an intelligence hub operating alongside the CIA base at RAF Croughton and is under the authority of the US Commander-in-Chief in Europe, whose operation is located in Stuttgart. The NATO Intelligence Fusion Centre was established at Molesworth in 2006 to provide electronic and satellite intelligence to NATO forces in Afghanistan and from 2008 for American forces in Africa (i.e. Libya and Somalia). (11)

Countering the Russian regime, the Committee suggested, should not stop at counter-espionage and preventing cyber-intrusion, money-laundering or the bribery of public officials but also involve offensive cyber warfare. It called for more resources for the National Offensive Cyber Programme set up by GCHQ and the Ministry of Defence in 2014. Until now, the Committee’s report suggests, offensive cyber campaigns have been directed at the Islamic State and other jihadi extremists operating abroad. The scope of Britain’s cyber warfare offensive should be widened, the Committee advocated, not only to weaken Russian economic and political influence in Asia and Africa, but also be extended against China, Iran and North Korea. “As a leading proponent of the rules-based international order it is essential that the UK helps to promote and shape rules of engagement, working with our allies … for a common international approach in relation to Offensive Cyber [operations]” the Committee concluded. (12)

In May 2019 the GCHQ Director, Jeremy Fleming, spoke to a reception for NATO ambassadors held at Lancaster House, London, on the occasion of NATO’s 70th Anniversary. Echoing the wording of the as yet unpublished Intelligence and Security Committee report, he talked of the need to work together to tackle common threats and to be prepared for cyber-attacks against NATO countries. He stressed that deterrence should go beyond cyber security and that what was needed was a framework that promoted the “responsible projection of a nation’s cyber capabilities”. (13) The GCHQ webpage states that: “We help to manage the threats to us and our allies from hostile states around the world. Our work also contributes to promoting the UK's prosperity and ensuring that the rules-based international system is upheld.” (14) In other words it involves economic espionage, propaganda and offensive cyber-intrusion against countries deemed hostile to the UK.

This year Britain established a National Cyber Force – a joint unit of the Ministry of Defence and GCHQ – with an initial budget of £76 million and specialist staff of 500. Just who the unit’s intended targets are has not been disclosed officially, but, with the current hubbub over Hong Kong and the supposed threats to UK’s critical national infrastructure from China, the People’s Republic must surely be included alongside Russia. Unfortunately, this escalation in hostilities is not just backed by the conservatives but by much of liberal opinion on the grounds that John Bull should stand up to “two overbearing foreign powers with hegemonistic tendencies”, as The Observer newspaper put it, for “balanced, boundaried relationships”. (15) The fact that all the emphasis has been put on alleged Russian and Chinese “bad behaviour”, while ignoring the intensification of cyber warfare by Britain itself, is deeply worrying.

(1) Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament, 2020, Russia, HC632, London: HMSO: paras. 12, 84 and 85.

(2) Dominic Grieve, The Russia problem can’t be delayed out of existence, The Guardian, 23 July 2020

(3) Marco Silva, General Election 2019: What’s the evidence that Russia interfered? BBC News, 11 March 2020 at <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-51776404>.

(4) Michael Savage, The Opinium/Observer poll: Nearly half think Moscow affected result, The Observer, 26 July 2020.

(5) Dominic Grieve, The Russia problem can’t be delayed out of existence, The Guardian, 23 July 2020.

(6) Anne Applebaum, columns in The Washington Post, 4 August 2017; 29 June 2017; 16 October 2015; and 25 July 2016.

(7) Lilia Shevtsova, Russia’s dual response to the West creates confusion on both sides, Financial Times, 1 September 2017.

(8) Cited by Natalie Nougayrède, Putin’s long game has been revealed, and the omens are bad for Europe, The Guardian, 19 March 2016.

(9) Anne Applebaum, The Washington Post, 25 February 2018.

(10) Intelligence and Security Committee: paras. 12, 125, 126, 130 and 144.

(11) Robert G Stielgel, 2018, The origin and evolution of the Joint Analysis Centre at RAF Molesworth, Studies in Intelligence, (62) 1, March: pp. 29-38, at <https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/csi-publications/csi-studies/studies/vol-62-no-1/pdfs/why-molesworth.pdf>.

(12) Intelligence and Security Committee: para. 18, 21 and 26.

(13) GCHQ post, Director GCHQ addresses NATO cyber defence pledge conference 2019 on 22 May 2019 at <https://www.gchq.gov.uk/news/director-gchq-addresses-nato-cyber-defence-pledge-conference-2019>.

(14) GCHQ webpage at <https://www.gchq.gov.uk/section/mission/strategic-advantage>.

(15) Lead opinion article, The Observer, 12 July 2020.

The claims made against Russia derive from a Cold War mindset that attributes almost everything said on Russian or Chinese social media to the Putin regime or the Chinese Communist Party.