Capitalism in a quagmire

by Noah Tucker

Do you remember when the thing about capitalism was that it was, supposedly, a dynamic system?

There was even a time not so long ago, between the rise of Margaret Thatcher and the fall of Gordon Brown, when Karl Marx’s lurid depictions of industrialisation and an earlier phase of globalisation were rediscovered and recited with awe, as an invocation to the spirits - cruel maybe but creative and fearsomely productive - unleashed by privatisation and deregulation.

Overlaying that was the political triumphalism of unipolar US power, with universal capitalist liberal democracy declared as the endpoint of human history. The link between these economic and the political levels was explicit in the work of the intellectual gurus of that period. Francis Fukuyama cited Marx in support of his theses, while trumpeting the “unabashed victory of economic and political liberalism” and the “triumph of the West”. (1)

CRACKS IN LIBERALISM

Matters for economic and political liberalism have since become distinctly abashed, and apparent, for example, in the cracks emerging in the so-called ‘rules-based international order’ (ie untrammeled US supremacy). This has been highlighted by the refusal of most of the world to accede to US positions on Ukraine and Palestine and in the worsening social and political difficulties within the rich capitalist countries.

In mid-December 2023, Britain’s major liberal-centrist newspaper, The Guardian, carried an editorial complaining of the “chronic syndrome causing toxic politics”. (2) Remarking the lack of productivity growth since 2008, and that real wages have “barely grown” (a misleading understatement - in fact real wages have fallen substantially for most workers (3)), it observed that public services “decay or vanish altogether”, added to “rising inequality and crime, poorer public health, and other symptoms of civic decline, putting greater pressure on services, which must then be subjected to ever tighter rationing.”

The Guardian editors continued: “This is how the economics of stagnation generates toxic politics. A country that is not expanding its collective wealth, still less distributing what it earns fairly, is drawn into a zero-sum game for resources…different priorities are sharpened into bitter rivalries. The longer an economy stagnates, the more fissiparous its society becomes. This is not the only cause of political malaise in Britain, but it is a significant factor and one that the Conservative government is more inclined to exploit than to fix.”

Of course, that editorial omitted another important effect – workers’ struggles and political movements which do genuinely attempt to address the issues – unsurprising given the role of The Guardian to always oppose or undermine any serious attempt at fairer distribution, let alone any change from the underlying capitalist economic structure.

But what of that previous period of vigorous capitalism? Emphasising the corrosive effect of rising inequality on prospects for economic growth, Martin Wolf of the Financial Times recently had this to say: “Thatcherism did not, alas, cause an enduring revival of the UK economy. Indeed, the growth prior to 2007 was itself in part an illusion. This must be admitted, at last.” (4)

CAPITALISM'S MISSING MOJO

Following the failure of the Western economies to recover from the 2008 financial meltdown, a phenomenon initially labelled as the ‘productivity puzzle’ began to attract academic and technical curiosity. Since the Covid pandemic and the failure of economic output to ‘bounce back’ after lockdown, this has burgeoned, via think tank reports and newspaper editorials, into worry about full-blown economic stagnation. So far, the search for the missing mojo of capitalism has produced mixed results. The fundamental problem cannot be in the ‘ageing population’, as the main factor in declining Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth is the lack of growth in output per worker, which ought to be on an upward trend with the adoption of technological developments.

Despite the UK’s lackluster performance, the timeline and the geographical spread of the problem shows that Brexit is not the key issue, nor is it anything solely affecting Britain. The main EU countries are currently on a similar course of stagnation to the UK, with Eurozone GDP in the third quarter of 2023 showing a slight contraction. (5)

One explanation for the extended flatlining of productivity was that the usual ‘creative destruction’ of capitalism (whereby production units that were using older technology, or were otherwise less efficient, are driven out of business by the market) was not taking place, because of ultra-low interest rates and the flood of money from quantitative easing. These policies adopted by the central banks to prevent further economic meltdown following the 2008 ‘credit crunch’, and again during lockdown, were shielding such firms and reducing their costs. However, the productivity problem originated well before these monetary measures and the steep rises in central bank interest rates since 2021 have not resulted in any perceptible rise in productivity. (6)

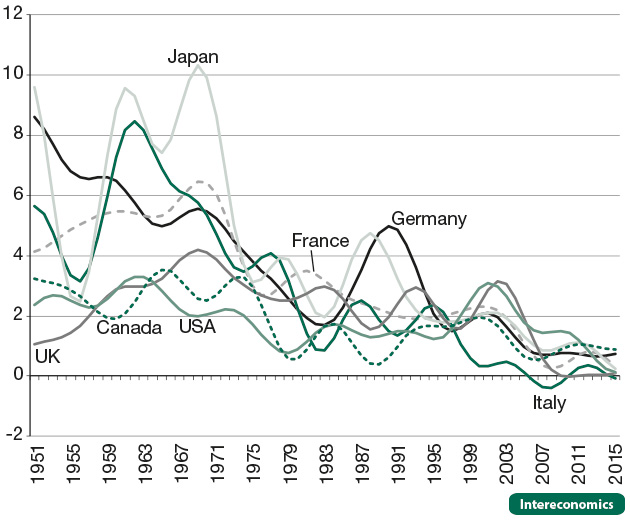

The graph in the figure opposite, of growth in output per worker in the G7 countries from the 1950s to 2015, uses the rather crude measure of GDP, and the ups and downs reflect booms and slumps, currency movements, and competitive international economic relationships. Nevertheless, the graph shows falling productivity growth rates to be a common feature of the major advanced capitalist countries since at least the early 1970s. Thus we can see that two explanations which may be put forward from a left perspective - the failure of neoliberalism, and the effect of low wages – cannot offer more than partial reasons for the economic sluggishness of advanced capitalism. While privatisation and deregulation have without doubt made the problem worse in the long term, the phenomenon of declining average productivity growth had its onset before the accession of Thatcher and Reagan. In fact, stalling GDP growth and associated economic difficulties of the 1970s were used as arguments for the changes which aimed at unleashing the powers of the market.

Further, it can indeed be surmised that low pay levels make a double contribution to low productivity: by keeping costs down, thus helping ‘less efficient’ firms to survive and additionally, by reducing the incentive for business owners to invest in labour-saving machinery. But while these factors are likely to be playing a role in the recent and current situation, productivity growth began falling even in periods when wages were rising due to trade union organisation and the beneficial context of widespread public ownership. (7)

A factor increasingly - and correctly - highlighted, even by ‘mainstream’ commentators and researchers, is that of low investment. But the questions need to be asked: investment in what, and why the low rate of investment?

SHRINKING REAL ECONOMY

The trend shown in the graph in Figure 2, on the levels of employment in manufacturing industry in the G7 countries, depicts lines following a similar trend to that of the declining productivity growth seen in Figure 1. Britain’s example is typical although more extreme than the others, with manufacturing employment falling from nearly one third of the workforce to only 10% over four decades. The proportion of manufacturing as a share of overall GDP fell nearly as steeply. (8)

While manufacturing industry is not the only productive sector, it is at the core of what has become known since 2008 as the ‘real economy’. This distinguishes it from activities such as financial services, advertising and marketing, speculation and real estate in which, as became clear particularly in the financial and property sectors during the 2008 crisis, the appearance of value creation is illusory. The shrinkage of manufacturing represents a trend in which an ever smaller proportion of economic activity involves production of the goods and services from which wealth and incomes are actually derived.

So what else are firms doing with the resources at their disposal? A paper by researchers for the Productivity Insights Network found that the top UK companies are following the US example by using ‘creative’ practices, with a diminishing relationship to earnings from production, to generate returns for shareholders (9)

PRODUCTIVITY INSIGHTS REPORT

The report says:

Purpose of research:

“[W]e explore whether a proportion of large UK firms follow their US counterparts in paying dividends and share buy-backs in excess of their declared income attributable to shareholders earned over a sustained period. In addition, we examine the productivity, investment, operating performance and impairment resilience profile of high distributing firms.”

Key findings:

- Big firms paid out more to shareholders than they earned in net profits. From 2009-19, the top 20% of ‘high distributing’ firms paid out 178 per cent of their net income to shareholders, and the next 20% of companies paid out 88 per cent of their earnings to shareholders. These two quintiles represented between them 60 percent of the market value of the sample of 182 companies in the in the FTSE 350.

- The top 20% of firms making the highest payouts to shareholders had the lowest growth in productivity (measured by sales growth and value added per employee). These companies also had the lowest growth in investment (capital expenditure).

- These practices, “reflective of a more financialized corporate world”, with “an enlarged role for financial engineering and creative accounting”, may be “crowding out investment-led productivity-enhancing strategies.”

In parallel, the global proportion of Research and Development (R&D) spending is shifting. Between 1960 and 2020, the US portion of world R&D declined from 61% to 31%. China is catching up and now ranks second, with $583 million (in Purchasing Power Parity) spent annually on R&D, compared to the USA on $721 million. (10)

FALLING RATE OF PROFIT

But this still leaves us with the issue of what lies at the root of these long term shifts that are resulting in lower and lower increments in productivity, in the loss of the economic dynamism of capitalism? The answer has a bearing on whether some tinkering with the system can significantly ameliorate matters, or whether the problem is more existential. A useful starting point here is to ask what, from the point of view of the owners and directors of economic resources under capitalism, is the purpose of investment, and indeed the purpose of production and all business activity? It is to make profits.

Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and the other classical political economists of two centuries ago, noted that under capitalism, the rate of profit tended to fall over time. This did not mean that the amount of profit for business owners would perpetually reduce, rather that the ratio of financial returns to investment would tend to reduce as time went on.

The basis of the problem that these classical economists identified is that profit is derived from the value produced by workers in production. In order to increase profits, the capitalist invests in more and better fixed capital (eg increasingly advanced machinery), and thus needs fewer workers. But, because the ultimate source of the profit is the capitalists’ economic relationship with the human workers (rather than with the equipment, raw materials etc) the reducing number of workers as against the rising value of the fixed capital eventually, and on average, results in the rate of profit being eroded.

This observation was supported and developed by Karl Marx. He cautioned that there were ways that capitalists could, and inevitably would, raise the amount of profits, and even temporarily the rate of profit, eg by increasing the working hours and reducing the wages of workers. And that there could be other countervailing tendencies, eg if the prices of the non-human inputs to the production process fell substantially. But in the long term, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall would result in ever increasing problems for the capitalist system itself. (11)

Figure 4, showing changes in the overall rate of profit in the G7 countries, reveals a trend which is consistent with these insights, as well as correlating with the data on productivity and the size of the manufacturing sector over the same period. And indeed, under capitalism there is no compulsion, or even expectation, for ‘investors’ to use the resources at their disposal for purposes that are beneficial for the development of the economy as a whole. On the contrary, they are supposed to find the highest return at the least (presumed) risk for that particular sum of potential capital. As the rate of profit on productive capital falls, other business activities – however unproductive or parasitic they are – become increasingly attractive as alternatives for the employment of financial resources.

WAY OUT?

Is there a way out of this economic quagmire?

Obscured by the petty rivalries and exposure of their venality and incompetence, the lack of any realistic solution (within the framework of the ‘free market’) to the phenomenon of flatlining productivity, underlies the dizzying turnover of Conservative UK prime ministers. No less than five of whom occupied that post during just over six years from 2016 to 2022. Of these, only Liz Truss showed any signs of a genuine belief in a way out of stagnation. The deluded nature of which was immediately proven by the same financial markets whose players should have been the prime beneficiaries of her programme. But even she suffered from a lack of political confidence, shown in her attempt to fund giveaways to the rich out of public borrowing, rather than via the more respectable/traditional way of directly robbing the poor; and that was her undoing. Currently, nobody expects - from either Sunak or Starmer - any substantial policy that could reverse Britain’s declining productivity growth.

Thus it seems likely that the liberal-centrist wing of the establishment, by the manipulations which defeated the potential Jeremy Corbyn premiership, has closed off, at least for the short term, any possible route by which UK capitalism could be saved from some of its own worst excesses, and has thus guaranteed a course of deepening economic corrosion. But given the fundamental nature of the issue at the centre of the stagnation problem, it is uncertain whether even the programme advanced in the Labour Party during the Corbyn leadership would have been radical enough to restore economic development in the UK. If implemented, the measures set out in the 2017 and 2019 Labour manifestos, although representing very major improvements for working class people, would not have been as extensive as the structural changes made by the Labour government that was elected in 1945 – and even those did not turn out to be enough.

(1) ‘The End of History?’ Francis Fukuyama, 1989 https://www.jstor.org/stable/24027184

(3) Cost-of-living crisis: UK real wages have fallen at a record rate - New Statesman

(4) Britain needs a way out of economic stagnation (ft.com)

(10) US Congress: Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R44283.pdf

(11) https://thenextrecession.wordpress.com/2020/07/25/a-world-rate-of-profit-a-new-approach/

Labour productivity trends in the G7

...because the ultimate source of the profit is the capitalists’ economic relationship with the human workers (rather than with the equipment, raw materials etc) the reducing number of workers as against the rising value of the fixed capital eventually, and on average, results in the rate of profit being eroded.