Barry Johnson 1931-2020 - a life in struggle for the working class

We pay tribute to our comrade Barry Johnson who was a founder member of the editorial board of The Socialist Correspondent. We will miss his thoughtful socialist analysis and passionate commitment to the struggle. This obituary is based on the oration given by his partner Hilary Cave at the well-attended memorial commemoration of his life held in Chesterfield on 17th February 2020.

Barry was the middle son born to Laura and George Johnson in Byron Street, Hucknall. Barry’s older brother Arthur has died, but his younger brother Don is with us. As Barry and Don grew up there was plenty of love, but little money, in the family. This was because their father had been sacked from his job in the pit after having been identified as a local strike leader in the 1926 dispute. After the end of the second world war, when his father had been able to return to mining, enough money was found to enable Barry to visit his French pen-friend Guy. This was the start of a very long friendship, with Barry and Guy staying at each other’s family homes. As both Barry’s parents were hard-working communists and community activists, he learned his politics at an early age. Before he was old enough to vote himself, Barry was involved in running general election Labour Party Committee Rooms in Hucknall. On leaving school Barry became a library assistant. Perhaps that was where he acquired his lifelong love of books, or perhaps he took the job because he already loved books.

In due course he was obliged to do National Service in the RAF, which he disliked. Barry told me that during this time national servicemen were being used to break a strike. He was furious about this, so when his name appeared on the list of those selected for the following week’s dirty work, he kept repeating to everyone that he would refuse to strike-break, no matter what. The officers in charge clearly did not want to take him on and have a public fuss, so as if by magic his name disappeared from the list of those ordered to break the strike.

Barry was married, then separated, with a son, Shuan, whose early death following an acute illness was a source of enormous grief.

STRUGGLES AND STUDIES

Barry worked in the International Department of Boots, where he quickly learned about the tricks employed by pharmaceutical firms to maximise their profits, often at the expense of people in poor countries. As an active member of USDAW he became involved in Nottingham Trades Council. Later, working on circulation for the Morning Star, he spent a lot of time campaigning in pit yards and other workplaces.

Barry was keen to undertake further study, so as a mature student he attended a Nottingham college of further education to gain his A Levels. Then he was able to give up paid work to attend Loughborough University, studying Economics and Economic History, which he loved. During this period he became heavily involved in the print workers’ struggle against a lock-out at the Nottingham Evening Post. His trades union campaigning experience and commitment were so highly valued that the union paid him a wage so he could afford to keep working on their campaign instead of spending his university holiday taxi-driving to earn money.

In the early 1970s Barry went to work at Chesterfield College, developing TUC courses for workplace reps, which he regarded as his dream job. Later he also worked on the radical Access course led by Angus Mclardy. Barry and I first met during the 1970s, when I too worked in trades union education.

In the period leading up to the Miners’ Strike, when we could all see that Thatcher’s government was intending to attack the miners and their industry, the labour movement in Chesterfield needed to select a Labour Party candidate for the general election. Of course there were many contenders, including an NUM member supported by his own union. At an advanced stage of the selection process Barry used his influence to persuade the NUM that they should vote for Tony Benn, rather than for their own member, as candidate. Tony was finally chosen, then elected. His support for the NUM, and his efforts on their behalf in the House of Commons, were magnificent, so for that and many other reasons, Tony was the best choice among the possible candidates. Barry’s persuasive skills had been useful to the movement.

THE MINERS STRIKE

During the 1984-5 Miners’ Strike Barry would get up very early to join the picket line at his nearest pit, Linby, close to Hucknall, before travelling to work in Chesterfield. As President of the Trades Council here, he worked tirelessly to support the NUM and the local Mining Women’s Support Group. Early on in the Strike, the Trades Council organised a march around Chesterfield to show support for the miners, ending in a rally on the Town Hall steps. We were joined by Yorkshire miners on their way to a march in Nottingham. At one point in his speech Barry praised those Notts miners who were on strike. There was a cry of “scabs” from one of the Yorkshire miners. Barry challenged him immediately, pointing out that it took more courage to be on strike in Notts, where most miners were working, than in Yorkshire, where the strike was solid.

Later in the Strike, Kate Whiteside, a miner’s wife and activist, had been asked to speak at the Trades Council. As the miners were getting no strike pay and the government had altered the regulations to remove benefits from any striking miner, the strike would have collapsed without food parcels supplied by the Women’s Support Group. Kate told us the group was very short of money, showing us a plastic carrier bag containing the small amount of food that was all they could afford to put into weekly parcels. Barry picked up the bag, waving it at the meeting, declaring, “This is our shame. We must raise more money for the miners, or they’ll be starved back to work.”

As I worked then for the NUM and knew the hardship being felt by mining families, I added my pleas to those of Barry. We both knew how important this battle was for the whole labour movement. Afterwards, some delegates, who preferred not to help the miners, accused us of haranguing them. Somehow neither of us felt guilty about this.

As President of the Trades Council, Barry was one of the founders of what is now Derbyshire Unemployed Workers’ Centres, advising people who are out of work, sick, disabled or precariously employed. It must be doing valuable work, because Derbyshire County Council, now Tory-controlled, has withdrawn every penny of their grant to it. North East Derbyshire District Council, also Tory-controlled, has cut our grant significantly, too.

Returning to the winter of 1985, as the Miners’ Strike was obviously in trouble, Derbyshire Women’s Support Groups organised a march to every pit in North Derbyshire. The weather was appalling, with snow and blizzards. Every time Barry could slip away from college for an hour or two he would march with the women as they struggled along their route. After the strike was lost, the resources of Nottingham miners were stolen, with court permission, by the breakaway outfit. Nottingham NUM Area had many newly-elected branch officials who needed training, but as the NUM’s National Education Officer I had no resources to do this. So Barry spent many weekends working with me as we trained this new generation of activists, mainly at Ollerton Miners’ Welfare. Barry did this work willingly, on top of his normal week’s work at college, without being paid a penny.

Barry had joined the Communist Party at an early age and although much later he became very unhappy with many of its positions, he refused to leave until it finally dissolved itself.

PERSONAL PASSIONS

What was Barry like as a person? I found him quiet, kind, thoughtful and affectionate. He taught me to enjoy opera and old buildings. Together we enjoyed the theatre and many types of music. Barry particularly admired Paul Robeson, not only for his marvellous voice, but also for his political stance. Barry always remembered, with emotion, attending a concert in Nottingham when Robeson was supposed to appear in person. Because the American government had withdrawn his passport, he was forced instead to sing in America, with his voice being relayed to Nottingham over the radio.

In his youth and middle age Barry had liked beer, but he later switched his affections to red wine and Armagnac. After the tremendous shock of a massive heart attack during his sixties, he became a keen walker, aiming to walk the entire Notts/Derbyshire border. He loved moors and had a special affection for Eyam Moor. As the years went on, he eventually needed a wheelchair and in good weather I used to wheel him along flatter parts of the High Peak Trail, Sherwood Forest and Chesterfield Canal, where he enjoyed the fresh air and wildlife. Until Barry’s illness prevented him from going anywhere at all, we enjoyed attending the local jazz club.

When Barry and I first became a couple, I discovered that he tended to regard holidays as a waste of good campaigning time. Visiting France, though, was a different matter in Barry’s eyes, so we had a number of lovely holidays there, sometimes visiting Barry’s friend Guy and his wife. During one holiday we saw a poster advertising a march in Poitiers organised by the CGT, a French trades union confederation, to protest against unemployment. When we turned up at the pre-march rally in a trades union hall, Barry approached one of the organisers to offer solidarity from Chesterfield Trades Council, then we took our seats unobtrusively at the back of the hall. We were taken aback to hear the platform speaker announce our presence, then invite us to stand up to be applauded. Feeling embarrassed by the warmth of our reception, Barry muttered “It’s the first time I’ve ever been applauded just for being a Brit!”

FURTHER STUDIES AND FINAL YEARS

A good few years into his retirement, Barry went to Leicester University to study part-time for an MA in Local History. He really loved this. I will read you a poem that sums up Barry’s approach to history, and to education in general. This approach is not officially popular these days. Written by Bertolt Brecht, who was forced to flee from Nazi Germany, the title of the poem is:

QUESTIONS FROM A WORKER WHO READS

Who built Thebes of the seven gates?

In the books you will find the names of kings.

Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock?

And Babylon, many times demolished

Who raised it up so many times? In what houses

Of gold-glittering Lima did the builders live?

Where, the evening that the Wall of China was finished

Did the masons go? Great Rome

Is full of triumphal arches. Who erected them? Over whom

Did the Caesars triumph? Had Byzantium, much praised in song

Only palaces for its inhabitants? Even in fabled Atlantis

The night the ocean engulfed it

The drowning still bawled for their slaves.

The young Alexander conquered India.

Was he alone?

Caesar beat the Gauls.

Did he not have even a cook with him?

Philip of Spain wept when his armada

Went down. Was he the only one to weep?

Frederick the Second won the Seven Years’ War. Who

Else won it?

Every page a victory.

Who cooked the feast for the victors?

Every ten years a great man.

Who paid the bill?

So many reports.

So many questions.

Barry was encouraged by his tutors to pursue research for a PhD. He enjoyed being part of various historians’ online groups, exchanging ideas, information, and sources. After years of study, Barry’s illness forced him to abandon his PhD studies, which he found upsetting. Later, his supervisor Professor Chris Wrigley offered to edit a paper Barry had written about the butty system in the pits, so our Labour History Society could publish it as a pamphlet. At least Barry had the satisfaction of seeing some of his research in print.

Well-read and passionate about learning, Barry helped to found the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Labour History Society, serving as its first chairperson. Having also helped to found Sheffield Humanist Society, he was active there for several years, also becoming a humanist funeral officiant.

The last twelve years of Barry’s life were very painful for both of us, as he became more and more incapacitated, both physically and intellectually. According to his wishes, I cared for him at home for ten of those years. Finally, on the instructions of a consultant, he was sent into St Michael’s nursing home for end-of-life care in September 2018. Barry was a fan of the Dylan Thomas approach to death:

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day:

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Initially resistant to living in care, as he became more and more ill, Barry developed close bonds with staff members there. My thanks to staff for the care and sensitivity with which Barry and I were treated, especially during and after his last days and hours of life. However, this period of illness was only a small part of his long and active life.

Barry, you will stay in our memories, our thoughts and in my heart always.

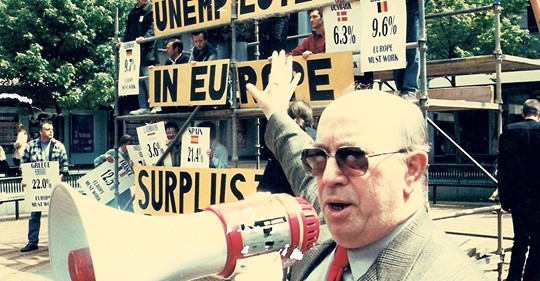

Barry with Arthur Scargill during the Miners Strike

Barry campaigning